The golf swing represents a fast, highly coordinated motor skill that showcases how biomechanical concepts apply to sport-specific performance. Biomechanics – the cross‑disciplinary field that uses mechanical principles to explain movement,force production,adn tissue loading in living systems – supplies the language and tools for dissecting the swing (including kinematic,kinetic,and neuromuscular analyses). An evidence‑driven biomechanical view clarifies how linked segment motions, intersegmental force transfer, and precise muscle timing generate clubhead speed and directional control, while also identifying the repetitive loads that can lead to injury.This review brings together contemporary biomechanical models and empirical data to describe the major mechanisms behind an effective, reproducible golf swing. Core themes include kinematic sequencing (proximal‑to‑distal activation and torso‑pelvis dissociation),kinetic contributors (ground reaction forces,joint moments,and power flow through the kinetic chain),and neuromuscular strategies (anticipatory postural adjustments,stretch‑shortening effects,and controlled motor variability). We also discuss how body proportions, equipment choices, and task constraints alter these determinants, and we summarize common injurious loading patterns affecting the lumbar spine, shoulder complex, and elbow. Methodologies used to quantify swing mechanics – 3D motion capture, force plate metrics, surface EMG, and musculoskeletal simulation – are highlighted to anchor coaching and clinical recommendations in measurable outcomes.

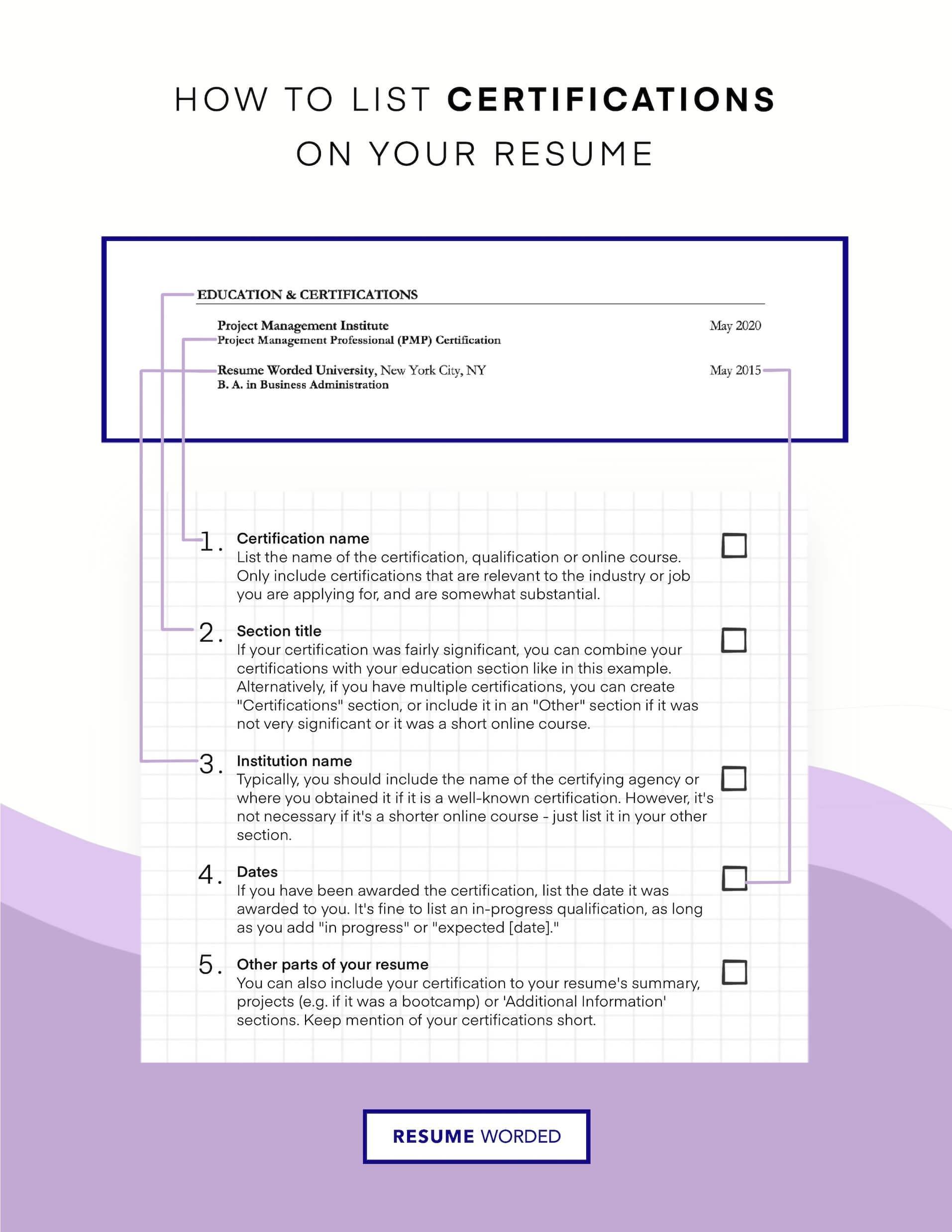

To translate raw sensor signals into actionable coaching and clinical insight, adopt standardized processing pipelines (filtering, coordinate transformations, and normalization) and focus on a core set of outcome variables that bridge research and practice. An iterative model‑validation and feedback loop is useful: computational models generate hypotheses (e.g., altering pelvis timing increases ball speed), experimental trials validate predictions, and data‑driven coaching protocols implement targeted changes while quantifying uncertainty and inter‑subject variability. Representative variables commonly used in applied settings include:

| Variable | Acquisition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Peak hip rotation velocity | Motion capture / IMU | Contribution to clubhead speed |

| Peak lumbar moment | Inverse dynamics (kinematics + GRF) | Spinal loading risk indicator |

| Onset of gluteus maximus EMG | Surface EMG | Sequencing and force‑transfer timing |

By merging principles from human movement science with applied biomechanics, this article aims to give coaches, clinicians, and performance specialists a concise mechanistic roadmap for technical refinement, training programming, and injury reduction. Emphasis is placed on converting quantitative findings into practical coaching prompts and conditioning plans that respect human physiology while enhancing performance.

Key kinematic Signatures of an Effective Golf Swing

Efficient transmission of mechanical energy through the body follows a reliable proximal‑to‑distal cascade: the pelvis starts the rotation, the torso follows, the upper arm and forearm accelerate, and the clubhead achieves peak speed last. This organized timing – often called the kinematic sequence – optimizes transfer of angular momentum by staggering peak angular velocities so each distal link peaks after its proximal driver. Motion‑capture research repeatedly links better performance with clear temporal separation between peaks rather than simply larger joint excursions.

The angular separation between pelvis and thorax (the familiar X‑factor) enhances elastic loading of trunk muscles and connective tissues via a controlled counter‑rotation in the backswing. During transition and the downswing, reducing that separation quickly engages stretch‑shortening mechanisms to amplify rotational output without requiring proportionally greater muscle force. While a moderate X‑factor boosts clubhead speed,overly large separation or abrupt recoil increases shear on the lumbar spine; the practical goal is a balance that maximizes power yet limits harmful loading.

Contact with the ground supplies the initial impulse for the kinematic chain: deliberate weight transfer, foot‑ground torque, and vertical push create the net moments that spin the pelvis. Ground reaction force (GRF) signals show phase‑specific patterns synchronized with segment rotations. The simplified summary below outlines the dominant GRF direction for major swing intervals,as reported in biomechanical studies.

| Phase | Dominant GRF direction | Functional Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Early downswing | Posterolateral drive | triggers pelvic rotation |

| Mid‑downswing | Vertical/medial surge | Stabilizes base; raises torque |

| Impact | Peak vertical force | Final energy transfer to ball |

The distal sequencing of hands and club depends on controlled wrist hinge and maintaining shaft lag for provided that feasible.Skilled players preserve a measurable lag into the downswing, timing forearm rotation and delayed wrist uncocking to produce a rapid late‑phase release. Kinematic evidence suggests that precise timing of forearm pronation and wrist extension-not simply maximal joint angles-is the major predictor of higher clubhead speed and tighter dispersion.

Consistent tempo and low trial‑to‑trial variability are crucial to reproducible kinematics. Observable checkpoints for video or motion capture include pelvis peak rotation preceding the thorax peak,distal progression of angular velocity peaks,and GRF transients aligned with downswing start. Useful coaching prompts grounded in biomechanics are: lead with the hips, keep your spine tilt, and hold the wrist release. These strategies support power production while increasing consistency.

kinetic Chain Mechanisms: From Feet to clubhead with Coaching Applications

The golf swing is a staged handover of mechanical work from ground to clubhead via an integrated kinetic chain. GRFs produced by the legs are the principal external energy source; effective swings convert vertical and horizontal GRF components into rotational momentum through coordinated joint torques. Segmental angular velocities progress proximal‑to‑distal – hips precede the torso, the torso precedes the shoulders, and so on – so that peak speeds are staggered to maximize clubhead output and limit concentrated internal stresses.Interruptions to this sequencing (for example, early upper‑body rotation or premature arm acceleration) create energy leaks that impair performance and raise injury risk.

Lower‑limb mechanics form the platform for force transfer. Generating useful force requires a stable base, timely hip extension with controlled internal rotation, and managed center‑of‑pressure (CoP) travel under the foot. hip extensors and adductors produce large moments early in the downswing while ankle and knee stiffness direct GRF orientation. Coaches should screen for bilateral force balance, lateral‑to‑medial CoP progression, and an ability to maintain vertical stiffness through impact; deficits frequently enough appear as lower ball speed or compensatory shoulder‑driven swings.

The trunk acts both as an energy reservoir and a transmission hub: transverse plane separation (the X‑factor) stores elastic energy that is then sequentially released toward the upper limb. Optimal trunk strategy emphasizes controlled stiffness – enough to limit harmful shear but flexible enough to hand off torque efficiently. Upper‑limb roles are largely about fine control and timing: scapulothoracic positioning aims the shoulder, the elbow adjusts lever length and extension speed, and the wrist times the launch by managing hinge and release. Effective players sustain wrist lag well into the downswing and follow impact with a managed deceleration pattern to protect shoulder and elbow tissues.

Coaching cues and progressions:

- Legs: “Push the lead side” – promote a lateral weight shift and dynamic hip drive through the downswing.

- Core: “Brace and rotate” – encourage midline tension with rib rotation rather than lumbar collapse.

- Arms/wrists: “keep the lag; release late” – delay wrist uncocking to lengthen the lever and boost clubhead speed.

- Sequencing drill: Step‑and‑turn – a small forward step initiates hip action, then the torso rotates to align proximal‑to‑distal timing.

- Safety: “Finish with control” – teach active deceleration through the lead arm and scapula to cut impulsive loads on elbow and shoulder.

When translating kinetic data into targets, example benchmarks used in applied assessments include:

| Metric | Example Target | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Peak vertical GRF | 1.5-2.2 × bodyweight | Force plate |

| Anterior shear impulse timing | Consistent at transition (~100-150 ms) | Force plate + time‑series |

| Peak hip moment | ~1.0-2.0 Nm·kg⁻¹ | Inverse dynamics |

Optimization should target both force production and temporal coordination. Recommended interventions include force‑application drills emphasizing horizontal shear and vertical impulse, sequencing training with resisted rotational throws, and strength & rate‑specific conditioning (eccentric‑to‑concentric hip and trunk programs). Technical cueing that increases center‑of‑pressure awareness and stance adjustments helps stabilize GRF patterns and reduce maladaptive compensations.

| Segment | biomechanical Purpose | Coaching Cue / Target |

|---|---|---|

| lower Limbs | GRF production; stable base | “Lead push” – lateral CoP shift, hip drive |

| core | Store & transmit energy; sequencing | “Brace and rotate” – maintain X‑factor suited to athlete |

| Upper Extremity | Fine control; release & deceleration | “Hold the lag” – delayed wrist release, tidy follow‑through |

Trunk‑Pelvis Phasing: Maximizing Transfer While Protecting the Spine

High‑quality energy transfer depends on a synchronized kinematic chain where the pelvis rotates first and the thorax follows after a controlled delay, generating intentional intersegmental separation that channels angular velocity to the hands. This temporal offset – conceptualized through the X‑factor and the X‑factor stretch – enables elastic loading of trunk muscles and lumbar connective tissues,enhancing output without relying solely on spinal torque. Preserving pelvic orientation relative to the femoral heads and rib cage helps maintain neutral spinal alignment and spreads loading across hip and core structures instead of concentrating shear in the lumbar segments.

Effective sequencing adheres to the proximal‑to‑distal pattern: the lower limb captures GRFs,the pelvis accelerates,and the thorax and shoulders uncouple later. Pelvic mechanics that support this include a small posterior tilt at transition to guard lumbar flexion, controlled trail‑leg hip internal rotation, and timely bracing of the lead leg to establish a rotation axis. These adjustments maintain coupling between pelvis and thorax while allowing high hand velocities without undue lumbar compromise.

Muscle coordination underpins both power and safety: concentric action from gluteus maximus and hip external rotators drives pelvic spin, while eccentric control from obliques, multifidus, and hip adductors regulates trunk deceleration. Conditioning that prioritizes eccentric capacity and rapid force production reduces cumulative microtrauma. The table below lists principal muscular contributors by phase and their functional roles.

| Phase | Key Muscles | role |

|---|---|---|

| Downswing initiation | Gluteus maximus, hamstrings | Pelvic acceleration; transfer of ground force |

| Peak separation | External & internal obliques | Store elastic energy; control thorax lag |

| Impact → follow‑through | Multifidus, erector spinae | Spinal stability; eccentric deceleration |

Several mechanical faults reduce transfer efficiency and heighten injury potential.Common issues include:

- Early thoracic rotation – diminishes pelvic input and raises lumbar torsion.

- Pelvic sliding (lateral shift) – wastes GRF and forces compensatory spinal motion.

- Weak lead‑leg brace – loses the rotational axis and increases shear at L4-L5.

- Excessive anterior pelvic tilt at transition – elevates facet loading and chronic extension stress.

Targeted cues and progressive drills can restore timing and increase resilience. effective interventions include:

- Tempo step drill – strengthens pelvic‑first sequencing (e.g., 3‑count backswing, pause, 1‑count downswing).

- Pause‑at‑top with mirror/video – encourages delayed thorax rotation and preserves separation.

- Medicine‑ball rotational throws – foster proximal‑to‑distal power and eccentric control.

- Single‑leg brace holds – build lead‑leg stiffness and pelvis stability under load.

Lower‑Limb Mechanics, GRFs and Balance: Foundations for Power and Control

The lower limbs are the golfer’s primary interface with the ground, generating and shaping the external forces that underpin clubhead velocity. GRFs are vector quantities with vertical, medial‑lateral, and anterior‑posterior components; their direction and timing determine joint moments at ankle, knee, and hip. Strong hip and knee extension combined with plantarflexor engagement turn GRFs into proximal rotational and translational impulses. Mechanically, the legs operate as a multi‑joint force generator and a rigid platform that allows the trunk to create and transmit angular momentum to the club.

sequencing of weight shift and foot pressure is vital for efficient transfer. During the downswing, the center of pressure (CoP) commonly shifts from the trail foot toward the lead foot with a transient lateral‑to‑medial migration that facilitates a late surge in vertical and horizontal GRF just before impact. A timely braking action from the trail leg establishes a stable axis for pelvic rotation, enhancing intersegmental energy flow. Excessive lateral sway or early unloading of the lead leg dissipates force and reduces energy delivered to the clubhead; aligning peak GRF timing with upper‑body rotation remains a key performance indicator.

Foot and ankle balance strategies preserve a reliable base under high dynamic loads. Skilled golfers display anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) and increased joint stiffness late in the downswing to resist rotational perturbation. Training should target controlled co‑contraction across the ankle‑knee‑hip chain to limit unwanted movement while preserving elastic return. Practical coaching cues include:

- Anchor the lead foot: keep toe‑down pressure through impact to orient the resultant force.

- Brace – don’t lock: raise stiffness without blocking rotation.

- Sequence the push: initiate lateral‑to‑medial trail‑foot pressure to augment transverse torque.

Conditioning drills can improve both power and stability by focusing on rapid force production, balance under perturbation, and single‑leg strength. Useful examples are single‑leg plyometric hops for explosive GRF, split‑stance medicine‑ball throws to practice cross‑chain transfer, and reactive balance tasks on unstable surfaces to refine CoP control. The concise table below lists sample drills, their mechanical focus, and a simple prescription.

| Drill | Mechanical Focus | Suggested Prescription |

|---|---|---|

| Single‑leg hops | Explosive vertical GRF | 3×8 each leg, 60-90 s rest |

| Split‑stance med‑ball throws | Transverse force transfer | 3×6 per side, moderate load |

| Reactive balance taps | CoP control & ankle stiffness | 4×30 s per stance |

Objective measures help refine technique and limit injury. Useful metrics include peak GRF magnitude, GRF vector orientation, CoP pathway, and timing of GRF peaks relative to clubhead acceleration; force plates and synchronized motion capture provide these data. Interpreting them allows practitioners to balance maximizing propulsive force against reducing harmful joint loads – such as, optimizing vertical/horizontal GRF ratios, conserving trunk rotation, and protecting hip and lumbar tissues via disciplined lower‑limb mechanics.

Shoulder,Elbow and Wrist at Impact: Alignment for Consistency and Reduced Loading

At ball contact the shoulder complex stabilizes and transfers rotational momentum from the trunk into the upper limb.Ideal impact geometry places the lead shoulder slightly adducted and depressed with the glenohumeral joint oriented to support a square clubface; the trail shoulder continues through the rotation to add momentum without excessive abduction. Smooth scapulothoracic rhythm minimizes compensatory humeral motion and preserves shoulder centration,improving repeatability of launch direction and spin. Accurate shoulder posture reduces face‑angle variability and limits pathological shear across the joint.

The elbows function as dynamic linkages that modulate transfer and attenuate impact forces. Optimal patterning shows the lead elbow near-but not into-full extension at impact, enabling energy transfer without hyperextension or medial elbow overload. The trail elbow usually remains slightly flexed to preserve wrist lag and support proximal‑to‑distal sequencing. From an injury perspective, maintaining physiological flexion at impact and avoiding sudden valgus/varus moments at the lead elbow is essential to lower tendon and ligament stress. Controlled elbow extension improves consistency while protecting the joint.

Wrist configuration at impact governs face orientation and contributes to distal velocity via release timing. A well‑timed release keeps wrist lag until just before impact, maximizing clubhead speed while the lead wrist remains neutral or slightly extended to square the face. Premature wrist collapse increases radial/ulnar deviation and lateral shear at the wrist and distal radioulnar joint, hurting launch consistency and increasing repetitive‑load risk. Coordinated forearm pronation through impact also helps close the face and promote compressive loading that yields predictable ball flight. Protecting wrist alignment in the final phase optimizes performance and reduces soft‑tissue strain.

Harmonizing shoulder, elbow and wrist mechanics relies on disciplined sequencing and practical coaching cues.Encourage proximal control, moderate grip pressure, and timing drills that keep wrist lag during the downswing to support efficient intersegmental transfer. Common cues and corrective focuses include:

- “Lead shoulder under the chin” – encourages correct adduction and face control.

- “Soft lead elbow” – defends against hyperextension and valgus stress.

- “Hold the wrist angle” – maintains lag and boosts distal speed.

These coaching points help reproduce impact geometry while lowering peak joint loads linked to injury.

For speedy reference, the matrix below summarizes target alignments and associated risks:

| Joint | Target at Impact | Risk if Deviant |

|---|---|---|

| Lead shoulder | Adducted & rotated | Face variability; shear loads |

| Lead elbow | Near‑neutral flexion | Medial overload |

| Wrist | Neutral / slight extension | Premature release; strain |

Consistent adherence to these alignments supports repeatable ball flight and reduces cumulative upper‑limb loading.

Neuromuscular Control, Motor Learning and Timing Interventions for Reliable Performance

Precision in the golf swing depends on finely timed, spatially coordinated muscle activations and strong sensorimotor integration. Models emphasize a proximal‑to‑distal activation pattern – pelvis rotation sparks a cascade through trunk and upper limb – accompanied by anticipatory postural adjustments that stabilize the base. Motor control theory frames this as an adaptable motor program: some timing variability is functional for adaptation, but excessive or unstructured variability undermines accuracy. Quantifying coordination therefore requires both kinematic phase relationships and neuromuscular timing measures (onset latency, burst durations) to capture the control strategy behind consistent performance.

Training to improve neuromuscular control should blend perceptual,timing,and strength elements to produce lasting improvements in reproducibility. Evidence‑supported modalities include:

- metronome tempo work to build consistent downswing timing and rhythm.

- EMG biofeedback to refine activation timing of critical muscles (obliques, gluteals, latissimus).

- Constraints‑led drills that manipulate task or environment factors to encourage effective motor solutions rather than rote technique.

- Variable practice schedules that intentionally change tee height, stance or target to develop adaptable timing.

Augmented feedback should be frequent initially and then faded to promote self‑regulation; adopt an external focus of attention (e.g., “push the turf behind the ball”) to accelerate implicit learning. Practical recommendations from applied research include using EMG biofeedback sessions 2-3×/week for 10-15 minutes to correct activation timing, prescribing plyometric/reactive drills 1-2×/week at low volume to improve rate of force development, and organizing variable practice in blocks of ~10-20 varied reps to foster adaptable motor patterns.

Timing drills should target the coupling between kinematic events (e.g., peak pelvis velocity, clubhead acceleration) and muscle activity. A commonly used tempo scaffold is a 3:1 backswing‑to‑downswing ratio (individualized as needed) to preserve consistent inter‑trial timing relationships. Combined feedback – auditory (metronome), visual (video kinematics) and haptic (wearables) – improves sensorimotor calibration and reduces phase drift, boosting both precision and repeatability under varying conditions and fatigue.

Clinicians and coaches require concise, actionable metrics to select and progress interventions. The table below pairs interventions with their primary mechanisms and expected short‑term outcomes:

| intervention | Main Mechanism | Short‑Term Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Metronome tempo drills | Temporal entrainment | Lower timing variability |

| EMG biofeedback | Selective activation timing | Improved muscle onset accuracy |

| Constraints‑led variability | Motor exploration | Greater adaptability |

Implementation should integrate assessment, staged progression, and injury risk management. wearable IMUs and targeted EMG can track intersegmental phase angles and burst timing during practice and simulated play; focus on improving temporal consistency not just ball outcome. Progress from high‑feedback, low‑pressure drills to lower‑feedback, competitive tasks to encourage internalization. Emphasize fatigue management and eccentric capacity of decelerative muscles to preserve timing under stress and lower overload injury risk, ensuring neuromuscular gains transfer to on‑course performance.

Typical Faults Linked to Lumbar and Rotator‑Cuff Problems and How to Correct Them

Lumbopelvic faults commonly present as early lumbar extension, lateral sway or a reverse spine angle during the downswing, and sustained hyperextension at impact. Mechanically, these patterns translate rotational demand into excessive sagittal compression and anterior shear, increasing disc and facet stress and interrupting efficient GRF transfer through the chain.contributing factors include restricted thoracic rotation,limited lead‑hip internal rotation,weak posterior chain muscles,and inadequate pre‑shot bracing – each forcing compensatory lumbar motion that,when repeated,raises injury risk.

Corrective approaches should restore mobility,rebuild neuromuscular control,and progressively strengthen the lumbopelvic stabilizers. Evidence supports combined strategies: thoracic mobility work and lead‑hip internal rotation stretching to reduce compensatory lumbar twist, followed by motor‑control training (transverse abdominis activation, multifidus recruitment) and progressive posterior‑chain loading (gluteal strengthening and Romanian deadlift variations). Practical drills include:

- Seated band thoracic rotations – reestablish thorax‑pelvis dissociation.

- Half‑swing emphasizing pelvic lead – promotes early pelvic rotation and limits extension.

- Dead‑bug with resisted trunk rotation – integrates core stability into rotational patterns.

Shoulder issues that increase rotator‑cuff strain often show as scapular dyskinesis, excessive humeral elevation at impact, abrupt late‑arm deceleration, or over‑reliance on the upper limb to generate speed (casting/early release). Poor proximal sequencing forces the shoulder to absorb peak velocity, increasing eccentric load on supraspinatus and infraspinatus and contributing to impingement or tendinopathy. Repetitive microtrauma compounded by acute overload commonly leads to symptomatic rotator cuff injury in golfers.

Rehabilitation combines tissue‑specific loading, scapular control training, and a graded return to swing. Evidence favors eccentric and isometric rotator‑cuff programs plus scapular stabilizer work (lower trapezius, serratus anterior) to lower tendon load and improve scapulothoracic mechanics. Useful exercises and progressions include:

- Side‑lying or banded external rotation – progressive cuff loading.

- Prone Y/T raises and serratus punches – recover upward rotation and posterior tilt.

- Progressive swing‑loading – short swings → 3/4 swings → full swings with tempo and kinetic‑chain emphasis.

Objective monitoring and staged return‑to‑play

| Fault | Metric to Track | Rehab Drill |

|---|---|---|

| early lumbar extension | frontal sway / trunk extension angle | Half‑swing with pelvic lead |

| Limited lead hip IR | Lead hip internal rotation (°) | Hip capsule mobilization + active IR drills |

| Scapular dyskinesis | scapular upward rotation symmetry | Prone Y/T and serratus punches |

Successful rehab and prevention involve a multidisciplinary, progression‑based plan: restore mobility, retrain motor patterns in low‑load contexts, progressively load tissues, and reintegrate swing mechanics with objective monitoring (kinematics, pain‑free load thresholds, and controlled practice volume). Prioritizing proximal sequencing and scapulothoracic control reliably reduces pathological lumbar and rotator cuff stresses while preserving needed speed and consistency.

Strength, Mobility and Motor‑Learning Strategies to Convert Biomechanics into Lasting Gains

Turning biomechanical insight into repeatable on‑course improvements requires integrated programs addressing force capacity, joint mobility, and neuromotor control. here, strength refers to the ability to produce and resist task‑specific forces (rotational, vertical, shear), while mobility denotes the segmental ranges necessary for efficient transfer. Focusing on a single quality without building the correct intersegmental mechanics can yield short‑lived gains that fail under fatigue or competitive stress.

Mobility training should reflect the swing’s demands: hip axial rotation, thoracic rotation/extension, adequate glenohumeral range for a stable lead side, and ankle dorsiflexion for balance. A pragmatic plan targets measurable improvements in these ranges while protecting load‑bearing tissues. Typical mobility priorities include:

- Hip rotation: maintain lead‑side internal rotation and trail‑side external rotation for effective X‑factor and weight shift.

- Thoracic extension/rotation: allow stacked shoulders over pelvis at the top of the backswing.

- Scapular‑humeral control: balance mobility with cuff and periscapular strength to prevent compensatory neck/head motion.

Strength work should be periodized to meet force‑velocity demands: build foundational strength → emphasize eccentric control → develop rotational power → transfer explosively to the club. The table below maps phases to objectives and representative exercises to assist planning:

| Phase | Goal | Example Exercises |

|---|---|---|

| Foundational | Maximal force & posture | Deadlift, split squat |

| Eccentric/control | Deceleration robustness | Nordics, slow‑tempo negatives |

| Power/transfer | Rotational speed & ballistic output | Med‑ball throws, Olympic lifts |

Motor‑learning bridges gym adaptations to on‑course skill: structured variability, deliberate practice with faded augmented feedback, and task‑specific constraints support retention and transfer. Programs should progress from blocked → random practice, reduce external KP (knowledge of performance) over time, and simulate representative states (e.g., fatigue) to ensure robustness. Practical implementations include:

- Variability in practice across swing speeds and lies to foster adaptability.

- reducing feedback frequency to strengthen internal error detection.

- Contextual interference training that mixes technical drills with short competitive tasks.

Durable gains arise when load,movement quality,and skill acquisition are monitored and periodized. Objective markers – clubhead speed (PGA‑level averages approximate 120-125 mph for drivers in recent seasons), pelvis‑thorax separation measures, movement screening scores, and pain‑free range – should guide progression and regression. emphasize progressive overload in strength phases, maintain mobility, and introduce graded exposure to high‑speed swings; together these elements lower injury risk while maximizing how biomechanical efficiency converts into consistent ball striking.

Practical, task‑relevant screening targets that help translate assessment into training are:

| Test | Practical Target | Monitoring Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic rotation (seated) | ≥ 45° each side | Monthly |

| Single‑leg eccentric control (step‑down) | < 10° pelvic drop | Biweekly |

| Med‑ball rotational throw (power) | Relative distance ≥ 1.5× athlete height | Every 4-6 weeks |

Q&A

Q: What does “biomechanical principles” mean for an effective golf swing?

A: In this setting, biomechanical principles describe the mechanical and physiological rules governing how the body produces, transfers, and dissipates forces and motion during the swing.They synthesize kinematics (segment positions and velocities), kinetics (forces, torques, power), and neuromuscular control (activation timing and coordination) to explain how clubhead velocity and shot consistency are achieved with minimized energy waste and injury risk. Biomechanics provides both theoretical models and measurement approaches used in sport analysis.Q: How is the swing typically segmented for biomechanical study?

A: Researchers commonly divide the swing into functional phases: address/setup,backswing,transition,downswing/acceleration,impact,and follow‑through. Each phase serves goals such as energy storage (backswing), reversal and sequencing (transition), and safe dissipation (follow‑through), which simplify measurement and interpretation.

Q: What is the kinematic sequence and why does it matter?

A: The kinematic sequence (proximal‑to‑distal) refers to the order of peak angular velocities across segments: pelvis → trunk → upper arm → forearm/club.This timing maximizes intersegmental energy transfer, increasing clubhead speed while spreading loads across the chain. Mistimed sequencing (e.g., early arm acceleration or delayed pelvic rotation) reduces efficiency and may raise joint stress.

Q: Which kinematic features most influence clubhead speed?

A: Key kinematic drivers include: (1) pelvic and trunk rotational velocities, (2) pelvis‑to‑thorax separation (torque potential), (3) lead‑leg extension and hip rotation during downswing, (4) wrist hinge and timely release to maximize distal angular speed, and (5) the club/hand path and plane. Both magnitude and phasing of these segmental velocities determine ultimate speed.

Q: What kinetic elements are essential for an efficient swing?

A: Critical kinetic inputs are GRFs that enable torque production, muscle‑generated joint moments, and intersegmental forces that shuttle energy distally. Efficient swings exploit vertical and horizontal GRF components to create net moments at hips and trunk that are sequenced to the upper limb and club.

Q: How do GRFs produce power in the swing?

A: GRFs let the golfer push against the ground and, via the ground’s reaction, establish a base for torque production through leg extension and rotation. rapid rises in vertical and horizontal GRFs at transition and early downswing correlate with larger pelvis moments and higher subsequent trunk and arm velocities. Effective leg use reduces load on the lumbar spine and upper limb.

Q: what role does the stretch‑shortening cycle (SSC) play?

A: Tendinous elasticity and SSC mechanisms assist rapid force generation during downswing and release. preloading during backswing and transition stores elastic energy which, if timed correctly in eccentric→concentric transitions (notably in trunk and hip muscles), enhances power and reduces metabolic demand.

Q: How are muscle activation patterns organized in a strong swing?

A: Neuromuscular coordination shows phasic,well‑timed activations: early activation of hip rotators/extensors starts the downswing,followed by trunk rotators and stabilizers,then shoulder and forearm muscles. Selective co‑contraction stabilizes joints (lumbar, shoulder) while allowing distal acceleration. Efficient patterns minimize needless antagonist activity during power phases.

Q: which measurement tools are used in swing research?

A: typical tools include 3D optical motion capture, inertial measurement units (IMUs), force plates (GRFs and CoP), surface EMG, high‑speed video, and inverse dynamics modeling. Portable sensors increase ecological validity but can trade off some precision relative to lab systems.

Q: What analyses turn raw data into useful metrics?

A: kinematics yield joint angles and angular velocities; inverse dynamics uses kinematics plus force data to estimate joint moments and powers. Time‑series methods, cross‑correlation, and principal component analysis evaluate sequencing and variability. Mechanical work and energy metrics quantify segment contributions.

Q: How does variability affect performance and injury risk?

A: some motor variability supports adaptation to changing situations. Excessive or poorly structured variability – especially in proximal‑to‑distal timing or trunk control – decreases clubhead speed and increases compensatory loading on passive tissues. Conversely, overly rigid technique can increase repetitive stress and chronic injury risk.

Q: What typical faults reduce efficiency?

A: Frequent faults include reduced pelvis‑trunk separation (low X‑factor), early casting/release, early extension (loss of hip flexion during transition), lateral hip sliding instead of rotation (wasting GRF), and poor sequencing (delayed pelvis rotation).Q: Which injuries commonly relate to swing mechanics and why?

A: Common complaints include lumbar pain from repeated rotation plus compression/extension/shear; shoulder problems (rotator cuff tendinopathy) from high accelerations and eccentric decelerations; medial elbow pain from repetitive flexor loading; and knee/hip overuse injuries from abrupt weight shifts. Biomechanical drivers include excessive spinal torsion under load, abrupt distal deceleration, poor lumbopelvic control, and underuse of lower‑limb propulsion.

Q: How can technique be changed to lower injury risk without losing performance?

A: Interventions focus on increasing pelvis‑trunk separation rather than excessive trunk rotation,improving efficient weight transfer and vertical force use through the legs,coaching delayed release (appropriate wrist mechanics),preventing early extension,and encouraging smooth accelerations to avoid abrupt joint loads. Individualize changes and validate them with objective measures.

Q: what physical training supports biomechanical efficiency?

A: A rounded program comprises mobility (thoracic, hip, ankle), lumbopelvic motor control, lower‑body strength and unilateral work, rotational power (medicine‑ball throws, cable chops), eccentric training for deceleration, and neuromuscular timing drills. Train progressively and align gym work with on‑course practice.

Q: How should practitioners use biomechanical data?

A: Use objective metrics to set clear goals (e.g., improve sequencing timing, raise pelvis angular velocity), identify constraints (mobility, strength, motor control), and measure intervention effects. Combine lab and field data for ecological validity, translate findings into usable cues and drills, and monitor for unintended technique shifts that raise injury risk.

Q: What are the main limitations of golf‑swing biomechanics?

A: Constraints include inter‑individual variability that limits universal prescriptions, lab vs on‑course behavior differences, measurement and modeling assumptions in inverse dynamics, and the complex interplay of psychological and perceptual factors that influence technique. Cross‑sectional designs commonly show associations, not causation.

Q: Where is the field heading?

A: Emerging trends include multi‑sensor wearable systems with real‑time feedback, machine‑learning personalization of technique, subject‑specific musculoskeletal modeling, and longitudinal links between biomechanical metrics and injury/performance outcomes. Blending physiological and perceptual measures with biomechanics will improve individualized training and rehab pathways.

Q: Where can readers learn more about biomechanics?

A: Introductory reviews and textbooks on biomechanics and human movement mechanics provide foundational concepts used in sport‑specific analyses such as the golf swing; these remain useful starting points for deeper study.

Concluding note: Biomechanical analysis offers a rigorous, evidence‑based framework for understanding and improving the golf swing. Its greatest value emerges when objective measurement, individualized physical profiling, and pragmatic coaching/rehabilitation strategies are combined and validated longitudinally for both performance gains and injury reduction.

Concluding Remarks

viewing the golf swing through biomechanical lenses – integrating kinematics,kinetics,and neuromuscular dynamics – clarifies how coordinated segmental motion,effective force transmission,and timely muscle activation underpin both performance and injury prevention. Treating biomechanics as the bridge between structure and function allows coaches and clinicians to move past generic cues toward evidence‑informed,individualized interventions that improve mechanics while honoring anatomical and physiological limits.

For practitioners,this synthesis highlights priorities: objective assessment (motion capture,force analysis,neuromuscular testing),targeted training to boost power transfer and postural resilience,and graduated load management to reduce overuse injuries. Motor‑learning strategies and task‑specific strength programs should be integrated with ongoing monitoring to tailor technique changes to the golfer’s body type, skill level, and injury history.

Looking ahead, continued collaboration among biomechanists, therapists, and coaches will be crucial to translate lab discoveries into practical, field‑ready protocols, refine prevention frameworks, and validate personalized training across diverse populations. Ultimately,a disciplined biomechanical approach provides a durable pathway to enhance performance and lower injury burden in modern golf.

Unlocking power and Precision: Biomechanics of a Winning Golf Swing

Use this article as a practical, evidence-informed roadmap to improve your golf swing mechanics, increase clubhead speed, and create more consistent ball striking. Below you’ll find clear biomechanical principles, motion-capture insights, drills, and tailored recommendations for beginners, coaches, and elite players.

why Biomechanics Matter for the Golf Swing

understanding golf swing biomechanics helps you convert athletic movement into reliable power and accuracy. Biomechanics links:

- Joint sequencing (proximal-to-distal transfer) – how hips, torso, arms and hands coordinate;

- Force production – ground reaction forces and how the body converts them into clubhead speed;

- Timing and tempo – creating repeatable sequencing for consistent ball striking;

- Clubface control – how grip, wrist set, and forearm rotation influence face angle at impact.

Key Components of an optimized Golf Swing

1. Grip Mechanics and Clubface Control

Grip influences clubface orientation throughout the swing and at impact. Aim for:

- Neutral to slightly strong grip for balanced face control and shot-shaping options.

- Even pressure-light enough to allow wrist hinge and forearm rotation, but firm enough to control the club.

- Consistent grip thickness and hand placement between sessions to reduce variability.

2. Setup, Stance, and Posture

Efficient setup primes the kinetic chain for power transfer:

- Feet shoulder-width (wider for long clubs slightly narrower for short irons).

- Athletic flex in knees, hip hinge with a straight but tilted spine.

- weight balanced slightly favoring the balls of the feet (~50-55% on lead foot for drivers).

- Shoulders, hips, knees aimed to create a square but athletic base that promotes rotation.

3. Coil, Separation, and the X-Factor

Power largely comes from creating separation between upper torso rotation and pelvic rotation (frequently enough called the X-factor). Optimal patterns:

- Controlled shoulder turn behind a more stable pelvis during the backswing, creating stored elastic energy in the torso.

- Efficient uncoiling beginning with the hips on transition – this sequencing produces a proximal-to-distal acceleration wave to the hands and club.

4.Sequencing and Kinetic Chain

Repeatable power requires correct timing:

- Hips start the downswing, followed by torso, then arms, wrists, and clubhead.

- Maintain lag (delayed wrist release) to maximize clubhead velocity, releasing near impact.

- Use ground forces – push into the ground toward the target to create higher clubhead speeds (front foot bracing at impact).

5.Impact Position and Follow-Through

Impact is a snapshot of good mechanics. Key markers:

- Clubface square or slightly closed to the target at impact (depending on shot shape).

- Hands slightly ahead of the ball for irons (forward shaft lean), promoting solid compression.

- Lower body rotated toward target, torso still slightly closed to allow extension through the shot.

Motion-capture Insights: What the Data Shows

Modern motion-capture studies and 3D kinematics reveal measurable differences between efficient and inefficient swings:

- Higher clubhead speed correlates with greater ground reaction force magnitude and faster proximal-to-distal sequencing.

- Elite golfers exhibit more consistent X-factor separation and controlled deceleration of the torso while accelerating the club.

- Excessive lateral sway, early extension, or overactive upper body reduces energy transfer and increases dispersion.

Simple Motion-Capture Indicators to Monitor

- Pelvic rotation vs. shoulder rotation at top of backswing (X-factor degrees).

- Timing of peak pelvic angular velocity relative to peak clubhead speed.

- Wrist hinge angle and preservation of lag during transition.

| Sequencing Checkpoint | Desired Timing | Coach Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis peak rotation | Initiates downswing | “Drive the belt buckle” |

| Thorax peak rotation | Follows pelvis by brief interval | “Chest clears toward target” |

| Forearm/club release | Peaks last | “Hold the angle, then let go” |

Practical Drills to Improve Biomechanics (Club and Range Drills)

Implement these drills to build the physical patterns that produce better contact, distance, and accuracy.

Drill 1 – The Step and Rotate (Ground Force + Sequencing)

- Setup with a mid-iron. Make a small lateral step with your lead foot toward the target during the start of the downswing.

- Focus on rotating the hips toward the target after the step, then allow the torso and arms to follow.

- Repeat with half-swings,building to full swings while maintaining lag and impact position.

Drill 2 – Towel Under Arm (Connected Arms and Torso)

- Place a small towel or headcover under your lead armpit during practice swings.

- The goal is to keep it from falling out-promotes connection between arm and torso and prevents disconnection at transition.

Drill 3 – Slow-Motion Impact Reps (Tempo & Path)

- Take slow swings to the impact position, pause at impact and check ball-first contact and forward shaft lean.

- Record or use mirror feedback for posture and shoulder tilt consistency.

Training Plan: 6-Week Focused progression

| week | Focus | Key Drill |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Setup & Grip | Mirror setup + grip alignment |

| 3-4 | Coil & Separation | Step & Rotate + medicine ball turns |

| 5 | Sequencing | slow-Motion Impact Reps |

| 6 | Power Integration | Full swings with launch monitor feedback |

Benefits and Practical Tips

- better ball striking: Improved compression and consistent contact reduce spin variability and improve distance control.

- Increased distance: Efficient sequencing and use of ground forces often add measurable yardage without sacrificing accuracy.

- More consistency: Reproducible setup and timing reduce shot dispersion and lower scores.

- Practice tip: Use a launch monitor or a high-speed camera every 2-3 weeks to measure progress on clubhead speed, smash factor, and attack angle.

Common Faults and Corrective Actions

- Early extension – lose posture through impact. Fix: hip hinge drills and impact pause reps.

- Overactive hands – flip or scoot through impact. Fix: delay release with holds at the top, and practice maintaining lag.

- Lateral sway – poor ground force request. Fix: foot pressure drills and step-and-rotate to encourage rotation over sliding.

Case Study: Applying Motion-Capture to Improve a mid-Handicap Golfer

player: 12-handicap, driver carry 230 yds, inconsistent strike.

- Baseline motion capture: excessive lateral sway, minimal X-factor, early wrist release.

- intervention: 4-week programme focusing on step-and-rotate, towel-under-arm, and pelvis-first sequencing.

- Result: Average clubhead speed increased 3 mph, carry distance increased ~12 yds, dispersion reduced by 15%.

Tailored Versions: Beginners, coaches, and Elite Players

beginners – Core Priorities

- Focus on a neutral grip and consistent setup. Master posture and balance before adding speed.

- Practice short swing repetitions (waist-high) to ingrain correct rotation and avoid compensations.

- Use simple feedback (mirror, impact tape) rather than complex metrics initially.

Coaches – assessment & Progression Tools

- Use slow-motion video (240-960 fps) for kinematic sequencing and shoulder/hip rotation timing analysis.

- Create objective checkpoints: pelvis rotation at top, X-factor angle, lag retention, and impact shaft lean.

- Prescribe drills that isolate one mechanical issue at a time and track client metrics with launch monitors.

Elite Players – Marginal Gains & Monitoring

- Prioritize ground force optimization, precise timing of peak angular velocities, and biomechanical symmetry.

- Incorporate strength & conditioning targeted to rotational power, hip mobility, and core stability.

- Use extensive motion-capture and force-plate data to make micro-adjustments to launch conditions.

Equipment and Technology That Help

- Launch monitors (track carry distance, ball speed, smash factor, spin) – critical for measuring improvements.

- High-speed video and 3D motion capture – diagnose sequencing and X-factor.

- Force plates and pressure mats – analyze ground reaction forces and foot pressure timing.

- Training aids (use sparingly) – alignment sticks, swing trainers, and impact tape for targeted feedback.

Quick Reference: Biomechanical Checklist at Impact

| marker | Ideal |

|---|---|

| Hands | Forward of ball (irons), neutral for driver |

| Clubface | Square to slightly closed |

| Hip Rotation | Open toward target; lead hip braced |

| Weight | 55-70% on lead foot (varies by club) |

| Spine Angle | Maintained from address (no early extension) |

Want a version tailored to a specific audience – detailed lesson plans for beginners, coach-ready assessment templates, or an elite player’s weekly program? Reply with which audience you want and I’ll build a customized 4-8 week program with drills, measurable goals, and video cues tailored to that group.