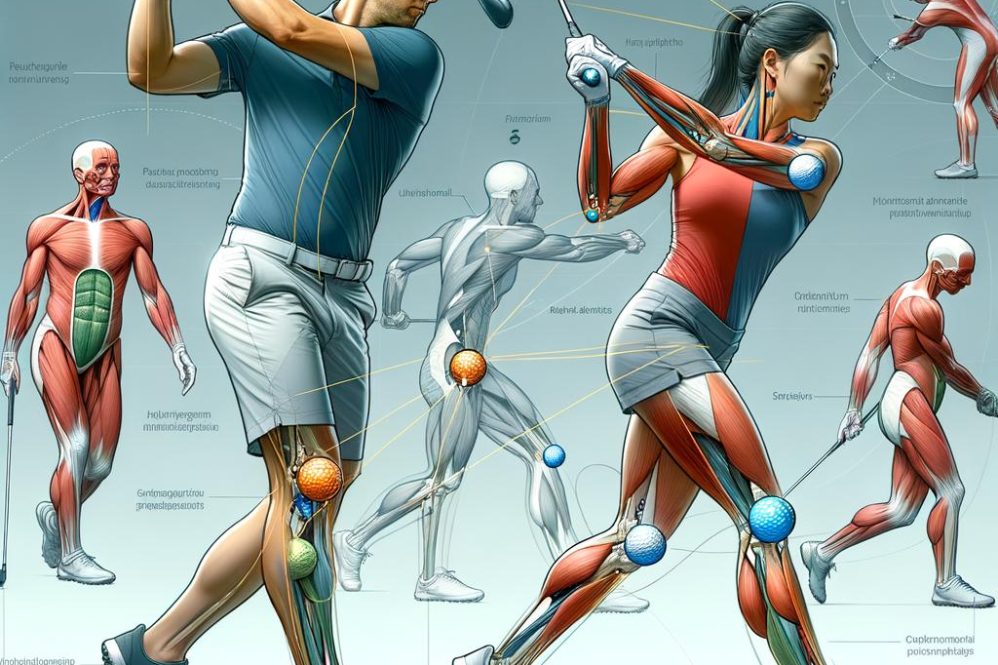

Biomechanics-the quantitative analysis of biological structure,motion,and function-offers a systematic lens for examining sport-specific movements and their controlling mechanisms. Applied to golf, biomechanical study moves past simple motion descriptions to investigate how muscle and joint segments coordinate, how neural timing governs action, and how external forces interact with the player. These methods have been pivotal in refining technique, raising performance ceilings, and lowering injury incidence across athletes.

The follow-through phase of the golf swing plays a key role in converting the preparatory motion and force production into repeatable ball trajectories and directional control. While instruction and research frequently emphasize the backswing and the moment of impact,the follow-through reveals how a swing is finished: how angular momentum is shed,how segments coordinate after impact,and how sensory feedback confirms or corrects the movement for consistency. Integrating three-dimensional kinematics, kinetic signatures, muscle activation patterns, and sensory feedback yields a fuller picture of how control and precision are produced and sustained across swings. This article collates current biomechanical insights about the follow-through-covering sequencing, muscular coordination, and feedback control-and links those findings to assessments and coaching strategies that help translate laboratory knowledge into on-course gains.

Sequencing, energy flow, and why the follow-through matters

During an efficient follow-through the body’s segments activate in a predictable proximal-to-distal order: the hips initiate rotation, the thorax follows, then the shoulders and arms, and finally the hands and club. That ordered timing produces favorable gradients of angular velocity so energy and speed are amplified as they move toward the clubhead. The precise timing between peak velocities (ofen measured as time‑to‑peak angular velocity) determines how much momentum from bigger, proximal segments is conserved and delivered to distal segments and ultimately to the ball.

Two mechanical concepts underpin efficient transfer: well-controlled torque production and conservation of angular momentum. The legs and hips generate ground reaction forces that establish a stable base and create pelvic torque; that torque is transmitted through the torso and stored briefly in musculotendinous structures via stretch‑shortening mechanisms. In competent swings, power tends to peak earlier in the pelvis and trunk and then later in the arms and wrists-this staggered power profile is characteristic of an effective kinetic chain and helps limit energy loss within the body.

Along with generating speed, the follow-through is the primary mechanism for controlled deceleration. A properly sequenced deceleration dissipates leftover angular momentum through coordinated eccentric muscle activity rather than abrupt joint braking, which woudl or else disturb clubface orientation at release. Sustaining dynamic balance-seen as a smooth center‑of‑pressure (CoP) progression and minimal corrective impulses in the legs-supports consistent club path and face angle at impact, improving directional accuracy.

Important, measurable coaching targets include:

- Proximal‑to‑distal timing: the order of peak angular velocities (pelvis → thorax → arms → club).

- Peak power distribution: relative contribution of hips, trunk and shoulders.

- Deceleration plan: eccentric control of forearms and trunk to keep the face stable.

- Balance indicators: CoP excursion and single‑leg hold time after impact.

These objective markers guide training plans that aim to increase the fraction of produced energy reaching the ball while protecting the fine control necessary for accuracy.

| Phase | Primary Contributor | Typical Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Hips/pelvis | ~100-60 ms pre-impact |

| Transmission | Thorax/shoulders | ~60-20 ms pre-impact |

| Release | Arms/wrists | ~20 ms pre-impact to impact |

| Dissipation | Forearms/trunk | Post-impact follow-through |

Targeted strength, plyometric and motor‑control work that sharpens these phase relationships can increase usable energy transfer to the ball without sacrificing distal control.

Lower‑body stability, weight shift and their effect on accuracy

The legs are the interface between player and ground and form the foundation for rotational power and directional control. Timely ground reaction forces (grfs) and limited uncontrolled side‑to‑side motion allow the proximal segments to sequence correctly through the follow‑through. Research and applied observation both show that a stable base reduces variation in clubface orientation at impact, tightening dispersion patterns on the course.

Proper redistribution of weight from the trail to lead side is both a kinematic and kinetic prerequisite for predictable ball flight. A deliberate medial‑to‑lateral center‑of‑pressure shift on the rear foot followed by progressive loading of the lead foot aligns the vertical GRF peak with the pelvis and torso’s peak angular velocity.When this timing is tuned, energy transmission becomes efficient and shot scatter narrows; when transfer is too early or too late, rotational timing breaks down and directional errors increase. In short, timing bridges force production and segment alignment.

Joint control at the ankle,knee and hip limits unwanted motion and refines the mechanical link from ground to club.Functional training goals include modulating ankle stiffness, improving frontal‑plane knee stability, and enhancing the lead hip’s external rotation capacity to absorb load. Practical drills that support these objectives include:

- Single‑leg balance holds (eyes closed) to sharpen proprioception and ankle strategies.

- Step‑and‑hold weight‑shift exercises that encourage a smooth CoP progression.

- Resisted hip‑turn movements that train eccentric absorption in the lead leg.

Useful assessment metrics are peak GRF timing, CoP excursion distance, mediolateral sway velocity and pelvis‑to‑thorax time lag. The short reference below summarizes typical desirable changes linked to greater precision:

| Variable | desired Change |

|---|---|

| CoP posterior→anterior excursion | Smoother, more progressive |

| Peak vertical GRF alignment | Earlier and aligned with pelvis peak |

| Mediolateral sway | Lower amplitude |

in practice, translate these principles into integrated stability and dynamic load‑acceptance training rather than isolated strength sets. Progressive overload using perturbation‑based balance tasks, tempo‑controlled swing reps, and force‑plate guided transfers reduces kinematic noise. In coaching and rehab contexts, favour drills that recreate the swing’s electromechanical timing so improved load acceptance yields repeatable clubface orientation and tighter shot patterns. precision emerges from predictable load routes and consistent temporal sequencing.

Distal control: wrist release, forearm rotation and keeping the face honest

The follow‑through is the distal completion of the kinetic chain begun in the legs and trunk; small, well‑timed motions in the arms, wrists and hands determine the clubhead’s final kinematics. How the lead and trail arms coordinate during deceleration influences residual torque about the shaft and therefore face orientation at ball release. Small timing deviations in these segments can cause outsized lateral dispersion, so distal motion is a major determinant of precision.

A controlled wrist release affects both clubhead velocity and launch behavior. Properly timed uncocking of the wrists converts stored elastic energy into club speed while regulating dynamic loft at impact and early ball flight. Too‑early or overly aggressive release raises dynamic loft and can open the face; a delayed or stifled release can tilt the face closed and induce hooking tendencies. Coaches should assess wrist extension/flexion ranges, radial/ulnar deviation patterns, and release speed together rather than in isolation.

Forearm rotation-pronation of the lead forearm paired with relative supination of the trail forearm after impact-helps tune face angle and dissipate residual torque. Controlled rotation in the follow‑through stabilizes the clubface and reduces side spin. Practical cues that support consistent rotation include:

- Keep grip pressure light through impact so natural pronation can occur.

- Use the forearms’ rotational arc rather than forcing movement through the wrists alone.

- Favor smooth deceleration-avoid abrupt stops that create compensatory forearm torque.

| Factor | Typical effect on outcome | Practical cue |

|---|---|---|

| Wrist release | Shapes launch angle and clubhead speed | “Allow the wrists to unhinge” |

| Forearm rotation | Controls face closure and side spin | “Rotate the lead forearm through” |

| Grip dynamics | Determines torque transfer to the club | “Lighten grip at impact” |

Trainable interventions target reproducible timing and sensory refinement of distal control. Useful practices include slow‑motion impact rehearsals, med‑ball rotational throws to pattern pronation, and band‑assisted wrist release repetitions to build coordinated uncocking without losing power. Objective monitoring-high‑speed video or inertial sensors-combined with progressive stability challenges reduces face‑angle variability and lateral dispersion, turning biomechanical insight into on‑course accuracy.

Timing strategies: from gross tempo to millisecond‑level sequencing

Segmental sequencing underpins dependable contact: a proximal‑to‑distal activation (pelvis → thorax → upper arm → forearm) creates a moving cascade of energy that must arrive at the clubhead within a narrow time window.Accurate arrival timing reduces variability in face orientation and effective loft; small timing shifts measured in tens of milliseconds translate into observable lateral and vertical dispersion. Training the relative onset latencies of major segments is thus a direct route to greater repeatability.

Macro tempo and micro‑timing operate together. Many coaching traditions recommend a backswing:downswing ratio near 3:1, but elite performance depends on micro‑events within the downswing-the pelvis deceleration point, torso counter‑rotation onset, and wrist release timing.Synchronizing weight transfer with rotational accelerations limits compensatory distal motions and steadies the clubhead’s approach to contact.

The simplified timing map below provides training‑oriented event markers and approximate relative timings:

| Event | relative Timing | Training cue |

|---|---|---|

| Transition (top → start downswing) | 0-10% | “Start with the lower body” |

| Maximum pelvic rotation rate | 20-45% | “Drive hips toward target” |

| Peak thorax rotation rate | 45-70% | “Keep chest behind hands” |

| Wrist un‑cocking / release | 75-95% | “Hold lag,then release” |

| Impact | 100% | “Square the face at contact” |

practical timing drills convert physiology into repeatable behaviors. Useful practice methods include metronome pacing for gross tempo,frame‑by‑frame video for micro‑timing,and constraint drills that isolate phases (e.g., pause‑at‑top, step‑in downswing). Key exercises:

- Metronome rhythm drill: establish a consistent backswing:downswing tempo.

- Pause‑at‑top drill: remove premature hand‑led starts and improve transition timing.

- Step‑and‑rotate drill: encourage coordinated weight shift and pelvic initiation.

objective feedback shortens the learning curve. Wearable IMUs, pressure insoles and high‑speed cameras provide timestamped kinematic and kinetic data that enable millisecond‑scale adjustments. Combined with progressive overload (increasing speed while preserving timing) and a standardized pre‑shot routine, measurement‑driven practice decreases impact variability: when temporal patterns are consistent, spatial outcomes tend to follow.

How GRFs and CoP behave during follow‑through

Shot consistency depends heavily on how the feet interact with the ground after impact. The vectors of ground reaction force (GRF) together with the instantaneous center of pressure (cop) location form the mechanical interface that controls deceleration, rotational impulse and balance recovery. Small changes in GRF direction or CoP trajectory during the follow‑through can travel up the chain, altering clubface orientation and increasing lateral or angular dispersion.

Mechanically,the follow‑through features a rapid reallocation of load from the back foot to the front and a posterior‑to‑anterior progression of forces under the lead foot. Vertical, medial‑lateral and anterior‑posterior GRF components show distinct temporal peaks: a dominant vertical impulse at impact followed by a sustained anterior‑posterior braking/propulsion exchange during the follow‑through. Concurrently, the CoP commonly moves forward toward the mid‑to‑forefoot and often drifts medially as the front leg stabilizes; the smoothness and magnitude of that CoP pathway relate to how consistently the clubface is controlled.

efficient follow‑throughs use a controlled GRF impulse and predictable CoP route to bleed off angular momentum while preserving club trajectory. Muscularly, coordinated eccentric work (hamstrings, gastrocnemius) absorbs rotational loads as the pelvis slows, then concentric stabilizers (gluteus medius, tibialis anterior) re‑center the CoP. Timing of these switches-observable as force rate changes and CoP velocity-is a sensitive index of whether energy transfer was effective or whether compensations will undermine precision.

For coaching and assessment, portable force plates and pressure‑mapping insoles deliver actionable metrics. Prioritize reliable measures: peak vertical GRF (normalized to body weight), CoP excursion magnitude and direction, CoP path length, and time to CoP stabilization after impact. Interventions include neuromuscular drills to smooth CoP progression, stance width adjustments to change the support base, and tempo work to align GRF peaks with desired rotation. Common field cues include:

- “Land and roll toward the front foot” – encourages a forward CoP shift without abrupt heel load.

- “Let the ground drive it, not the arms” – emphasizes lower‑body generation of follow‑through impulse.

- “Finish tall and centered” – promotes balanced CoP stabilization and orderly GRF decay.

| Metric | Recreational (typ.) | Elite (typ.) |

|---|---|---|

| Peak vertical GRF (% body wt) | 1.4-1.8 | 2.0-2.6 |

| CoP anterior shift (cm) | 6-10 | 10-16 |

| CoP path length (cm) post‑impact | 12-20 | 8-14 |

Neuromuscular control and learning methods to make the follow‑through reliable

Follow‑through quality is as much neuromuscular as mechanical: dependable terminal kinematics rely on well‑timed muscle activations, anticipatory postural adjustments and rapid feedback corrections.Feedforward motor programs create the broad intersegmental sequencing needed for a stable finish, while feedback processes fine‑tune face orientation and deceleration in the final 100-200 ms around contact.Biomechanically, consistent follow‑throughs appear when agonist‑antagonist timing, joint stiffness regulation and distal‑to‑proximal recoil are reproduced across repetitions.

Motor learning approaches that speed and stabilize those patterns include variable practice schedules, limiting verbose technical instruction to encourage implicit learning, and phased augmented feedback (e.g., showing outcomes before movement details). drills that focus on sensory prediction and constrained error exposure help internalize safe deceleration and club path. Field‑ready tasks include:

- Reduced‑vision swings (occluded or blurred video) to increase proprioceptive reliance.

- Constraint‑led exercises that change base of support or ball position to bias preferred solutions.

- Fading feedback blocks (gradually reducing video/EMG/force feedback) to move control to intrinsic cues.

Objective measurement is central to neuromuscular training. Tools include surface EMG for muscle onset and co‑contraction patterns; IMUs or motion capture for sequencing and angular velocities; and force plates for weight transfer and deceleration timing.Clinical labs may add electrophysiologic tests to validate neuromuscular function-useful in high‑performance settings to confirm adaptation rather than fatigue or pathology.

| measurement | Primary utility |

|---|---|

| Surface EMG | Muscle onset timing and co‑contraction indices |

| Inertial sensors / Motion capture | Segmental sequencing and angular velocity |

| Force platforms | Weight transfer and deceleration forces |

Design practice for retention and transfer by manipulating task structure and attentional focus. Use external focus cues (e.g., imagery of club path or target), introduce systematic variability, and progressively increase neuromuscular demands (speed, force, complexity). A simple coach’s checklist:

- Prescribe variability: change task parameters between reps.

- Fade feedback: reduce augmented cues over time.

- Test retention: check performance after a no‑feedback delay.

These steps embed robust neuromotor control so a technically sound follow‑through remains precise and repeatable under competitive pressure.

Typical follow‑through faults and practical, evidence‑aligned fixes

Common termination‑phase errors include early release (casting), incomplete arm extension, insufficient trunk rotation, excessive lateral sway, and loss of lead‑leg support. Biomechanically, such deviations interrupt the ideal proximal‑to‑distal flow and change clubface orientation at and after impact, increasing dispersion and producing less favorable launch conditions. For instance, early release wastes stored wrist energy and poor trunk rotation limits angular transfer from pelvis to shoulders-both reduce clubhead speed and consistency.

Choose corrective methods that target the specific mechanical fault and its physical cause. Proven interventions include:

- Delayed‑release drills (towel‑under‑arm, impact bag) to teach rear‑wrist retention and late uncocking.

- Extension/finish drills (finish‑hold with alignment pole) to promote full arm extension and a balanced finish.

- Rotational sequencing work (medicine‑ball throws, resisted trunk rotations) to restore pelvis‑to‑shoulder timing.

- Balance and single‑leg stability training to prevent lateral sway and secure lead‑leg support in the finish.

Rehab and conditioning should accompany technical correction for durable gains. Target thoracic mobility, hip rotation strength, scapular stabilization and anti‑rotation core capacity to support the kinematic chain. The table below links common faults to typical physical deficits and focused corrective actions:

| Observed Fault | Common Physical Deficit | Targeted Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Early release | Poor wrist/forearm eccentric control | Impact bag; eccentric wrist strengthening |

| Insufficient rotation | Limited thoracic mobility | Thoracic mobility drills; med‑ball throws |

| Lateral sway | Weak single‑leg stability | Single‑leg balance; hip abductor strengthening |

Use motor learning strategies-video feedback, launch‑monitor data, pressure‑sensor biofeedback-with an external focus to speed transfer to on‑course performance. Progress from slow, technically focused reps to full‑speed, situational practice under increasing complexity to encourage neuromuscular adaptation while limiting compensatory patterns.

Make implementation pragmatic and measurable: set objective targets (reduced dispersion,greater peak rotation velocity,stable finish posture) and re‑test with simple tools (phone video,launch monitor,balance mat). Short, evidence‑based milestones can include: (1) maintaining a balanced finish for 2 seconds across 20 consecutive swings, (2) clinician‑verified gains in thoracic rotation range, and (3) reduced variability in clubface angle at impact. Combining biomechanical correction with structured conditioning produces the best improvements in precision and control during the follow‑through.

Objective measurement: lab‑grade tools and field validation

Quantifying follow‑through mechanics requires both laboratory precision and field validation. High‑speed motion capture paired with force plate data yields temporally exact descriptions of sequencing and ground interaction, while on‑course metrics-launch monitors and dispersion statistics-link those descriptors to real shot outcomes. Together, these multimodal datasets move evaluation from subjective observation to reproducible numerical markers of control.

From motion capture extract three key domains: timing of the pelvis‑thorax‑arm sequence, angular velocity peaks and their intersegment delays, and endpoint kinematics of the club and hands at impact and early finish. both marker‑based and modern markerless systems can provide these measures,but adequate sampling (≥250 Hz for marker systems; ≥120 Hz for sturdy markerless setups) and careful anatomical calibration are essential to resolve the short‑latency events that affect dispersion. Derived metrics-time to peak angular velocity and intra‑trial variability of segmental timing-are particularly sensitive to precision problems.

Force plates add complementary kinetic information: vertical and horizontal GRF profiles, CoP migration, and impulse integrals across the downswing and follow‑through. Aligning GRF peaks with clubhead impact (phase‑locked analysis) reveals whether ground strategies support reliable energy transfer or introduce destabilizing torques. Bilateral asymmetries and CoP path curvature during the transition and follow‑through also correlate with lateral dispersion and shot curvature.

To connect lab data to on‑course relevance, collect a compact set of outcome measures in the field or in a matched session. Recommended targets include:

- Sequencing latency: ms difference between pelvic and thoracic peak angular velocities.

- Lateral CoP displacement: peak medial‑lateral shift during the transition.

- Vertical impulse at impact: normalized to body mass.

- Clubhead speed at impact: absolute value and variability (SD).

- Shot dispersion (CEP): circular error probable from multiple strikes.

Practical protocols require synchronization and a tiered sampling approach: high‑precision lab collection (motion capture ≥250 Hz + force plates ≥1000 Hz) plus launch monitor telemetry for field validation. The table below summarizes minimal technical specs for useful assessment:

| Signal | Min. Sampling | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Motion capture | 250 Hz | Resolve sub‑50 ms sequencing events |

| force plate | 1000 hz | Accurate impulse and GRF timing |

| Launch monitor | Instantaneous | Link ball and club outcomes |

Program design and drill prescriptions to tighten precision

Modern training for the follow‑through centers on task‑specific motor learning, graduated constraint manipulation and measurable, outcome‑driven practice. Treat the follow‑through as the integrated endpoint of sequencing rather than an isolated cosmetic pose. Structure drills that reinforce proximal‑to‑distal transfer, deceleration control and target‑oriented outcomes. Core principles are specificity, repetition with variability, and progressive withdrawal of external feedback to build durable sensorimotor changes.

Organize practice into stages that mirror skill acquisition: acquisition, consolidation and transfer. Example prescriptions:

- Acquisition: simple drills with frequent, clear feedback to establish correct movement patterns (e.g., slow‑motion full swings with feel cues).

- Consolidation: increase tempo and add variability to stabilize the pattern under different constraints (e.g.,alternating target distances and lies).

- Transfer: context‑rich, pressure‑informed tasks requiring choice and adaptability (e.g., simulated on‑course scenarios with performance targets).

Progression should be data‑driven-move athletes forward only when retention criteria are met.

Below is a compact drill matrix suitable for weekly practice; it’s short, actionable and adaptable:

| drill | Primary focus | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Finish | Deceleration & alignment | 3×10 slow swings |

| Target Ladder | Precision under variability | 4 targets × 6 shots |

| Tempo Meter | Rhythm & timing | 5 sets × 8 swings |

| Mirror + Video | Kinesthetic awareness | 2×5‑minute feedback blocks |

Objective feedback accelerates gains. Combine internal and external modalities: video for kinematics, launch monitors for outcomes, tactile or auditory cues for immediate correction. Track metrics such as:

- Club path and face angle at impact

- Smash factor and ball speed for energy transfer

- Post‑impact torso rotation as a proxy for follow‑through completeness

Log progress with retention checks and transfer tasks to ensure learning generalizes outside the practice environment.

Integrate training into a periodized microcycle balancing technical sessions, outcome‑focused practice and recovery. Example week: a slow, technical session emphasizing controlled finish (session A); an on‑course transfer session with variable targets (session B); and a mixed intensity session combining tempo and precision under pressure (session C). Reduce augmented feedback across the week and schedule routine benchmarks. Short,focused practice blocks with measurable goals produce the most reliable improvements in precision,consistency and control.

Q&A

1. What is the “follow‑through” and why does it matter for precision?

Answer: The follow‑through is the continuation of the swing after the ball leaves the face, including the ongoing motion of the club and the body until the swing stops. While the instant of impact sets initial ball speed and launch, the follow‑through reveals how well the kinematic sequence and force control were executed. A clean follow‑through signals efficient energy transfer, managed deceleration and good balance-all correlates of repeatable clubface orientation and shot precision.

2. how does sequencing during the follow‑through affect shot accuracy?

Answer: Sequencing is the proximal‑to‑distal timing were larger segments (hips, torso) initiate rotation and hand off momentum to smaller, distal segments. A preserved sequence through the follow‑through suggests efficient energy transfer; disruptions indicate timing errors or compensations that can change clubhead speed, path and face angle at impact, increasing variability.

3. What energy‑transfer mechanisms during the swing influence the follow‑through?

Answer: Energy transfer operates via segmental summation: rotational energy from the lower body and pelvis moves through the torso and arms to the club. Ground reaction forces and force couples generate the torques that start rotation. The follow‑through reflects how residual energy is let out-gradual, coordinated deceleration preserves consistent impact mechanics; abrupt deceleration or early dissipation can alter clubhead dynamics and reduce precision.

4. What role do GRFs and footwork play in the follow‑through?

Answer: GRFs provide the external support required to create rotational torque. Correct weight transfer and foot‑ground interaction (push through the trail foot, brace with the lead foot) build a stable base for rotation and a controlled finish. Erratic GRF patterns lead to timing errors, decreased rotational speed or excessive lateral motion, all of which affect club path and face control.

5. How does dynamic balance help accuracy?

Answer: Dynamic balance is the ability to manage the body’s center of mass over a support base while moving. A steady posture and controlled center‑of‑mass path through and after impact reduce sway and compensatory motions that would otherwise disturb clubface alignment. Better balance typically equates to less kinematic variability and improved shot precision.

6. Which body parts are most critically important for a precise follow‑through?

Answer: The pelvis and trunk supply rotational power and timing; the upper limbs refine and transmit club motion; and the hips and lower limbs create force and stability on the ground. A mobile, controlled pelvis and well‑timed trunk rotation are especially central to consistent finishes and outcomes.

7. How do wrists and hands influence face orientation during the follow‑through?

Answer: The hands and wrists make final adjustments to clubface rotation in the milliseconds around impact and during the early follow‑through. Proper release timing and stable wrists through contact help maintain the intended face angle. Early or late hand deceleration or compensatory wrist action can change face rotation and reduce accuracy.

8. What tools are used to analyze follow‑through biomechanics?

Answer: Common measurement tools include 3D motion capture systems, high‑speed video, force plates for GRFs and CoP, surface electromyography (EMG) for muscle timing, and inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field kinematics. These methods quantify segmental angles, angular velocities, sequencing, GRF patterns and muscle coordination that underpin follow‑through control.

9. How can coaches use biomechanics to improve follow‑through precision?

Answer: Coaches should emphasize drills that support correct sequencing, stable lower‑body support and controlled deceleration. Wearable sensors and video can reveal timing errors.Programmatic work should address mobility, strength (hips and core), and proprioception for balance. Objective measures-sequence charts and GRF traces-help individualize interventions and track progress.

10. Which training methods reduce variability and improve control?

Answer: Effective approaches include rhythm and tempo drills (metronome work), hip and core strength/power training, mobility routines for full rotation, single‑leg balance work, and technique drills that promote full extension and gentle deceleration. Plyometrics and rotational med‑ball work develop coordinated power transfer relevant to follow‑through control.

11. What common faulty follow‑through patterns reduce precision and why do they occur?

Answer: Faults include truncated follow‑throughs, forward collapse, hanging back or overactive hand flips. Causes span poor weight transfer, limited mobility, timing compensations, inadequate strength, fatigue or conscious manipulation to “steer” the ball.Each fault has identifiable kinematic signatures measurable with video or motion analysis.

12. How does follow‑through relate to injury risk?

Answer: Flawed follow‑through mechanics can increase repetitive stress on the lumbar spine and overload the elbows or wrists due to asymmetric forces. Excessive uncontrolled torques from poor core stability or limited mobility raise injury risk. Biomechanical screening helps pinpoint hazardous loading so training can reduce risk while enhancing performance.

13. Are individual differences critically important for prescribing follow‑through mechanics?

Answer: Absolutely. Anthropometry, joint ranges, injury history, strength profiles and skill level influence the most suitable follow‑through for a player.General principles apply, but specific targets and drills should be tailored.

14. What research is needed to better link follow‑through biomechanics with precision?

Answer: Needed areas include longitudinal studies tying quantified follow‑through metrics to on‑course dispersion, research into how individual differences alter optimal sequencing, integration of neuromuscular control models with biomechanics to explain intra‑player variability, and development of validated wearable measures that predict precision outside labs.

15. Fast cues and drills players can use immediately to improve follow‑through precision:

Answer: Try cues like “Finish tall and balanced,” “Drive the hips through to the target,” and “Let the hands release naturally.” Drills include slow‑motion swings to groove proximal‑to‑distal timing, med‑ball rotational throws for hip‑to‑shoulder transfer, one‑leg balance swings for dynamic stability, and impact tape or video to link feel with face behavior.Pair technical work with mobility, strength and balance training for lasting gains.

sources and further reading: foundational biomechanics texts and applied resources (clinical biomechanics overviews, university biomechanics groups and reputable applied fitness outlets) provide deeper context and practical applications.

Final summary

The biomechanical perspective on the golf follow‑through unites sequencing, controlled energy transfer and postural regulation as central drivers of shot precision. Theory and empirical work indicate that a consistent proximal‑to‑distal pattern, deliberate dissipation of residual energies, and maintained balance during deceleration reduce variability at contact and improve directional consistency. These concepts connect core biomechanical theory with actionable coaching cues and conditioning prescriptions.

For coaches and clinicians, integrating objective movement analysis-whether via high‑speed video, inertial sensors or lab motion capture-allows targeted interventions that refine timing, strengthen stabilizers and train athletes to execute controlled follow‑throughs under pressure. Equipment and swing adjustments should be informed by individual anthropometrics, mobility and injury history: optimal mechanics are person‑specific.

For researchers, the follow‑through offers fertile ground for longitudinal training trials, fatigue paradigms and field‑validated protocols that clarify causal links between mechanistic markers and shot consistency. standardized outcome metrics, larger cohorts and multimodal studies that combine biomechanics, neuromuscular control and perception will deepen our understanding of real‑world performance.

Ultimately, improving precision through follow‑through biomechanics requires collaboration among biomechanists, coaches, physiotherapists and equipment specialists. Converting lab discoveries into scalable coaching strategies and individualized training programs is the most promising path to sustainably improving accuracy while minimizing injury. Ongoing dialog between science and practice will sharpen these principles and help convert biomechanical insights into measurable, on‑course gains.

Mastering the Follow-through: biomechanics for Pinpoint Precision (Performance Tone)

Why the follow-through matters: more than a finish pose

The follow-through is the visible result of everything that happened earlier in your golf swing. It’s not just a flourish – it’s a feedback signal.A balanced, properly sequenced follow-through reflects effective weight transfer, efficient rotation, controlled clubface release and correct timing of the kinetic chain. When those biomechanical pieces line up, you get consistent distance, tighter dispersion and better shot-shaping control.

Core biomechanical principles that shape the follow-through

1. Kinetic sequencing (proximal-to-distal activation)

Efficient swings move energy from large, central body segments to the smaller distal segments: hips → torso → shoulders → arms → hands → club. That proximal-to-distal activation is the engine of power and tempo. A delayed or reversed sequence causes deceleration before impact, inconsistent contact and weak follow-throughs.

2. Ground reaction force and weight transfer

Powerful, stable swings begin with the ground. Pushing into the ground creates ground reaction forces that drive hip rotation and create a stable platform for upper-body rotation. Proper weight transfer (rear to front foot before and through impact) enables a high finish position with balance maintained on the lead leg.

3. Angular momentum and rotational acceleration

Torso and pelvis rotation generate angular velocity that the arms and club tap into. Controlling rotational acceleration through impact – not stopping it – allows the club to continue accelerating into the follow-through, keeping the clubface square through impact and minimizing sidespin.

4. Clubface control and release mechanics

The timing of the wrist release and forearm rotation determines face angle at impact. A proper release produces a follow-through where the clubhead travels on a predictable arc and the shaft finishes wrapped around the lead shoulder (for most swings), indicating a square or intended face orientation through impact.

5. Balance and posture maintenance

A stable spine angle through impact and an upright, controlled finish position are hallmarks of a repeatable swing. Loss of posture leads to thin or fat shots and misdirected follow-throughs. The final pose is an easy diagnostic: if you can’t hold a balanced finish,earlier mechanics need attention.

Follow-through goals by shot type

| Shot Type | follow-Through Marker | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Driver | Long arc, balanced on lead foot, club high and around | Maximizes launch and reduces deceleration through impact |

| Long irons / Hybrids | Controlled extension, slightly lower finish than driver | Balances distance control and accuracy |

| Wedges / Pitching | Compact, hands finish slightly lower, soft release | better feel, improved spin and stopping power |

common faults and their follow-through signatures

- Early deceleration: Short, collapsed follow-through with the club stopping abruptly – frequently enough caused by casting or flipping. Fix by maintaining lag and trusting the rotation.

- Over-rotation/rolling onto toes: Excessive lateral movement in the follow-through – often results from trying to “hit harder” and leads to loss of strike quality.

- Open clubface at impact: Follow-through with the club pointing outside the target line and low finish – indicates late release or wrist cupping.

- Loss of posture: Stooped finish or falling away from target – commonly caused by insufficient hip rotation or poor core stability.

Practical follow-through checklist (use this on the range)

- Finish balanced on lead foot with at least 70% of weight forward.

- Chest faces the target or slightly left of it (for right-handers) with hips open.

- Club points over or behind the shoulder, shaft roughly parallel to target line.

- Hands are high enough to indicate full extension through impact.

- no abrupt deceleration – the club keeps moving through and after impact.

Progressive drills to improve follow-through and sequencing

1. Half-swing to Finish Hold (Tempo & Balance)

- Take half swings and hold full finish for 3-5 seconds. Focus on weight transfer and a steady spine angle.

- Progress to three-quarter swings and then full swings while maintaining the finish hold.

2. Pause-at-Impact Drill (Timing & Release)

- Make swings where you pause briefly at the impact zone, then continue into the follow-through. This teaches the body to maintain speed through impact and discourages early deceleration.

3. Towel-Under-Arm Drill (Connected Upper body)

- Place a small towel under your trail armpit on the backswing and keep it there through the follow-through. Promotes connection between body and arms for a single rotating unit.

4. Step-Through Drill (Weight Transfer)

- Address the ball normally, then at impact step the trail foot forward into a balanced finish. This exaggerates weight transfer and helps feel pushing into the ground.

5. Medicine-ball Rotational Throws (Power & Sequencing)

- From athletic stance,hold a light medicine ball and rotate explosively toward a target,extending arms through the motion. Improves pelvic-thoracic separation and transfer of power into the arms for a robust follow-through.

Coaching cues that convert biomechanical theory into feel

- “Rotate the hips, then let the arms follow” – emphasizes proximal-to-distal sequencing.

- “Push the ground away” – focuses attention on ground reaction force and leg drive.

- “Brush through the ball” – helps prevent flipping and encourages a smooth release.

- “Finish tall and relaxed” – aids posture and prevents collapsing through the shot.

Programming a 4-week follow-through betterment plan

| Week | Focus | Drills (3-4 sessions / week) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Balance & finish holds | Half-swing finish hold, towel drill, balance stands |

| 2 | Sequencing & tempo | Pause-at-impact, step-through, slow motion swings |

| 3 | Power & rotation | Medicine-ball throws, driving range long shots with focus on rotation |

| 4 | Integration & pressure | On-course play, simulated pressure reps, mix of clubs |

Small adjustments that yield big returns

- Grip pressure: Keep it firm but not tight.Excessive grip tension kills wrist release and inhibits a free follow-through.

- Stance width: Slightly wider for drivers to stabilize the base and enable a longer arc; narrower for wedges to control swing width and finish height.

- Club selection awareness: A full aggressive follow-through for driver, more compact for wedge shots – match finish to intended ball flight.

Case study (practical example)

A mid-handicap player struggled with inconsistency and a tendency to fade off the tee. Analysis revealed early arm casting and inadequate hip rotation.A 6-week plan emphasized towel-under-arm and medicine-ball drills, plus pause-at-impact exercises. After focused practice, the player reported a more compact, connected transition, a smoother release and a balanced finish on >80% of swings. Dispersion tightened by 15-20 yards and the fade reduced to a controlled shot shape. This shows how targeted follow-through work translates quickly to on-course improvement.

First-hand practice tips from coaches

- Practice slow-motion swings to ingrain correct sequencing – speed up only after the movement pattern is solid.

- Use video (face-on and down-the-line) to check finish positions and rotation; small visual corrections are powerful.

- Practice with purpose: every rep should have a single focus (balance, release, rotation) rather than mindless swings.

SEO and search-friendly keywords included (naturally)

Throughout this guide you’ll see actionable terms that help both learning and discoverability: golf follow-through,biomechanics,golf swing,swing sequencing,weight transfer,clubface control,balance,timing,power,distance control,follow-through drills,and finish position.

Fast troubleshooting flowchart (what to check first)

- If the finish is short and the ball is weak → check for casting/early release and work on lag/rotation.

- If you can’t hold balance → focus on weight transfer and decrease swing width temporarily.

- If shots start curving unpredictably → record clubface at impact and tune release timing.

Ready-to-use swing-sequencing mantra

“Ground → Hips → Torso → Arms → club.” Use this as a pre-shot mental cue to align your intention with the biomechanics that produce a reliable follow-through.

Want this article tailored for amateurs (simpler drills and cues) or for touring pros (high-velocity sequencing, force-plate metrics and training periodization)? Tell me which tone and audience you prefer – technical, performance, or inspirational – and I’ll refine the headline, drills and coaching language accordingly.