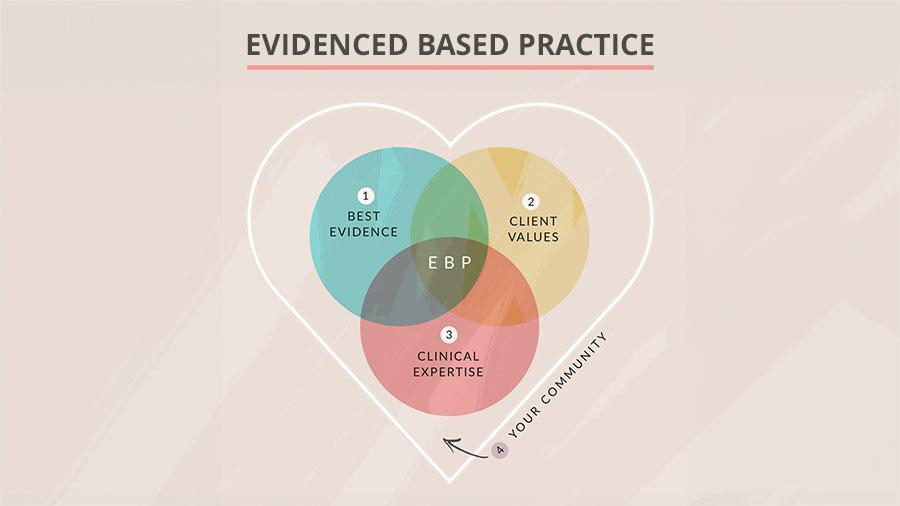

Putting is a determinative element of scoring in golf: small systematic improvements in stroke consistency, alignment, and distance control translate directly into fewer strokes and measurable performance gains. Despite extensive coaching lore and anecdotal advice,the scientific literature on putting – spanning biomechanics,motor learning,visual perception,and applied coaching studies – provides a firmer basis for selecting techniques that reliably improve precision. This article synthesizes that empirical work to identify which grip, stance, and alignment strategies are supported by data, how those strategies interact with individual differences (e.g., handedness, putting style, and skill level), and which training protocols produce durable improvements on the green.

We adopt an evidence-based framework, drawing on randomized trials, controlled laboratory studies, field measurements (e.g., strokes gained, putts per round, and dispersion metrics), and biomechanical analyses (motion capture, force-plate, and eye-tracking studies). Emphasis is placed on translating mechanisms – such as stabilizing the putterface, optimizing the kinematic sequence, and structuring practice and feedback to enhance motor retention – into concrete, implementable prescriptions for golfers and coaches. Where empirical findings conflict or are limited, we highlight gaps and propose directions for future research.

By grounding practical recommendations in peer-reviewed evidence and measurable outcomes, this article aims to move putting instruction toward greater precision, reproducibility, and performance impact – enabling players and coaches to prioritize interventions that demonstrably reduce variability and improve putting success.

Note on terminology: the phrase “evidence-based” is used here as a compound modifier and is hyphenated accordingly, following standard usage guidance.

Grip Mechanics and Contact pressure: Optimal Hand Positioning and Quantified Pressure Ranges for Consistent Ball Roll

Effective control of the putter face originates in precise hand placement and minimal,reproducible muscular activation. For most players a neutral wrist, hands slightly ahead of the ball at setup, and a grip that places the shaft along the lifelines of the fingers produces the most stable face orientation through impact. The lead hand (left hand for right‑handed golfers) should dominate fine rotational control of the clubface while the trail hand provides supportive guidance; this creates a functional asymmetry that reduces unwanted wrist collapse. Maintain a relaxed forearm and avoid gripping in the palm-contact pressure should be delivered predominantly through the pads of the fingers to preserve tactile feedback and micro‑adjustability during the stroke.

Quantifying grip pressure allows practitioners to replace subjective feeling with reproducible targets. Two practical scales work well in coaching and practice: a subjective 1-10 perceptual scale and an objective percentage of maximum voluntary contraction (%MVC). Recommended targets for consistent roll are: 3-4/10 (≈10-20% MVC) for most short, tempo‑driven putts and 4-6/10 (≈15-30% MVC) when additional stability is required for longer lag putts. Pressures below the lower range increase face variability; pressures above the upper range elevate muscular tension and reduce freedom of stroke. Use these ranges as training anchors rather than absolute prescriptions-individual anthropometrics and putter mass may shift optimal values within the bands.

| Perceptual Scale | Approx. %MVC | Practical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | < 10% | Too light – unstable face rotation |

| 3-4 | 10-20% | Optimal – consistent roll, low tension |

| 5-6 | 20-30% | Stable but increased tension; useful for long lag putts |

| 7-10 | >30% | Excessive – restricts stroke rythm and feel |

Practical calibration drills accelerate sensorimotor adaptation and internalization of target pressures. Useful exercises include:

- Pressure meter Feedback – practice with a simple pressure sensor or grip dynamometer to associate numeric feedback with sensation.

- 3‑2‑1 Drill – perform three putts at 4/10, two at 5/10, one at 3/10 to explore performance envelopes.

- Lead‑Hand Emphasis – perform strokes with reduced trail‑hand pressure (approx. 40% of total) to train face control through the lead hand.

- Mirror/Video Check – verify that minimal hand motion and consistent face alignment accompany target pressure ranges.

For durable transfer to the course, integrate short, focused pressure calibration into the regular warm‑up: record baseline values, practice 10-15 minutes using the 3-4/10 anchor on a variety of distances, then reassess performance metrics (roll quality, dispersion). Use objective tools where available (pressure mats,wearable sensors) to create a longitudinal record and adjust targets as technique and confidence evolve. Consistent application of these quantified hand‑pressure principles reduces variability in face control,yielding more repeatable impact conditions and a truer,more predictable ball roll.

Stance and Posture Alignment: Biomechanical Foundations and Prescriptive adjustments for Stable setup

The mechanical integrity of a reliable putting setup arises from predictable relationships among the base of support, centre of mass, and kinematic chain from shoulders to hands. Empirical analyses of putting strokes indicate that small deviations in joint angles at the hips, knees, and thoracic spine produce amplified variance at the putter head.Consequently, emphasis should be placed on establishing repeatable anatomical landmarks rather than aesthetic positions: consistent hip flexion, a stable lumbar angle, and minimal compensatory torso rotation reduce inter-shot variability. Stability is therefore best conceptualized as controlled constraint of degrees of freedom rather than rigid immobility.

foot placement governs the width of the support polygon and directly influences medio-lateral sway and rotational tendencies during the stroke. Prescriptive adjustments should be tailored to putt length and individual anthropometry: slightly narrower-than-shoulder widths favor short,precision putts while shoulder-width or marginally wider stances improve rotational control for longer strokes. Clinical measurements and on-course testing frequently enough recommend small, repeatable offsets (e.g., 0-5 cm medial or lateral) rather than wholesale changes. Below are evidence-informed position variants clinicians and coaches use:

- Neutral-width: shoulders-width; balanced weight; optimal for mid-range control.

- Narrow precision: 5-10% narrower than shoulder-width; lowers moment arm for short putts.

- Wide stability: shoulder-width plus 5-10%; increases rotational inertia for longer strokes.

Alignment of the spine, pelvis, and head determines relation of the eyes to the target line and affects perceived aim.A slight anterior pelvic tilt with neutral lumbar curvature positions the shoulders to hinge on a consistent axis and maintains the putter arc in a plane that reduces wrist compensation. Eye position that is directly over-or marginally inside- the ball produces the most consistent visual cueing for target line and roll-read; deviations anteriorly or posteriorly introduce parallax error.Coaches should cue neutral neck and relaxed jaw to minimize micro-adjustments that translate into head movement.

Load distribution and balance control modulate subtle lateral shifts during the stroke and are modifiable through simple feedback and drills. A target static weight distribution of approximately 50/50 to 55/45 (lead/trail) provides a stable baseline; uphill or downhill putts require proportional adjustments informed by slope angle. The following compact reference summarizes practical targets for setup variables:

| Element | Target | Practical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Stance width | Shoulder ± 5-10% | Shorter = precision; wider = stability |

| Spine angle | 20°-30° anterior tilt | Maintain neutral lumbar curve |

| Weight [% lead/trail] | 50/50-55/45 | Adjust for slope; test on-level first |

Operationalizing these adjustments requires objective verification (video, launch monitors, or pressure mat) and brief, repeatable pre-putt checks. Useful coaching cues include “soft knees,” “light grip pressure,” and “pendulum from shoulders”; incorporate short drills that isolate one variable (e.g., stance-width ladder, spine-angle mirror checks, or weight-distribution plates). Systematic measurement and incremental change-rather than wholesale reconfiguration-optimize motor learning and transfer to pressure situations.

Visual and Clubface Alignment: Perceptual Strategies and Calibration protocols to Reduce Aiming Error

Precise control of the clubface relative to the intended target line is the primary mechanical determinant of initial ball direction; consequently, perceptual miscalibration between visual aiming and actual clubface orientation is a leading source of putting error. Empirical work in perceptual-motor control emphasizes that small angular deviations at impact produce disproportionately large lateral misses at common putting distances. To minimize variability, practitioners should treat alignment as a sensorimotor problem requiring both accurate visual specification of the aim point and repeatable motor calibration of the putter face. Clubface orientation and visual aim must therefore be trained together rather than separately.

Effective perceptual strategies begin with simplifying the visual task: reduce the aiming target to a single,high-contrast anchor (e.g., the low edge of a hole liner, a blade of grass, or a sharply marked seam on the ball) and stabilize gaze on that anchor during address and the stroke. Use of an intermediate target 1-2 metres beyond the ball ofen improves alignment accuracy by creating a collinear visual reference. Practitioners should also assess and accommodate ocular dominance when establishing stance and sight lines: small lateral shifts of the head or ball that align the dominant eye with the aim point can measurably reduce systematic bias. adopt a consistent pre-shot gaze routine to ensure that visual specification of the line precedes and guides the motor program for the stroke.

Calibration protocols rely on repeated, feedback-rich drills that link perceived alignment to veridical outcomes. Recommended exercises include:

- Mirror face-check – immediate visual confirmation of putter-face angle at address and impact groove;

- Alignment-stick rail – long visual line placed behind the putt to align shoulders, putter path and face;

- Gate drill – narrow target gates to enforce square face through the stroke;

- Laser/shaft tracer – real-time visual feedback of face and path to accelerate error detection;

- Two-ball lateral bias test – short-series analysis of bias by aiming at two nearby marks and quantifying lateral deviation.

these drills are scalable in complexity and can be combined with augmented feedback (video, lasers) early in learning and faded to encourage internalized calibration.

Objective measurement and a staged calibration protocol improve retention and transfer. Begin with short-range (1-2 m) closed-loop trials where immediate feedback is given, then progress to variable-distance and pressure-manipulation phases. The table below summarizes a concise three-stage protocol useful for practice sessions:

| Stage | Focus | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration | High-feedback drills (mirror/laser) | 10-15 min |

| Validation | Intermediate targets, reduced feedback | 15-20 min |

| transfer | Variable distances, competitive pressure | 10-20 min |

To translate laboratory gains to on-course performance, follow two principles: (1) progressively remove augmented feedback to promote internal error detection and (2) embed alignment checks within a stable pre-shot routine so that calibration becomes automatic under pressure. In practice this means using high-fidelity feedback early in a session, running validation blocks with minimal feedback, and concluding with competitive, pressure-conditioned putts that simulate tournament constraints. Emphasize consistency of the visual anchor and the square-face check; when these elements are trained together, reduction in aiming error is robust and durable across competitive contexts. consistency, measured practice, and systematic feedback fading are the key levers for reducing alignment-related misses.

Stroke Kinematics and Tempo Control: Evidence-Based Patterns for Pendulum Motion and Acceleration Profiles

contemporary biomechanical analyses converge on a model of putting as a constrained pendulum action dominated by the shoulders and torso, with minimal distal wrist and hand interference. Electromyographic and motion-capture studies indicate that when the stroke is driven primarily from a stable shoulder axis, clubhead path variability decreases and repeatability increases. Consequently, coaching emphasis should be placed on maintaining a rigid forearm-shoulder relationship, controlling lateral head movement, and minimizing independent wrist flexion/extension that introduces high-frequency noise into the kinematic chain. Consistency of the proximal drivers-not torqueful distal manipulation-correlates most strongly with putting accuracy in empirical studies.

Temporal structure is a critical determinant of outcome. Evidence-based tempo patterns commonly report a backswing-to-forward-swing duration ratio near 2:1, with slower, controlled backswing and a deliberately paced acceleration through impact.Absolute durations scale with putt length, but the relative timing remains a robust invariant across skilled performers. The following compact reference gives practical target durations to use during training (rounded averages drawn from time-series analyses of proficient putters):

| Putts (approx.) | Backswing (s) | Forward (s) | Ratio (Back:Forward) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short (1-3 ft) | 0.40 | 0.20 | 2:1 |

| Mid (6-12 ft) | 0.70 | 0.35 | 2:1 |

| Long (15+ ft) | 1.10 | 0.55 | 2:1 |

Acceleration profiles across the transition are as important as timing. High-performing strokes typically exhibit a smooth, monotonic increase in clubhead velocity through impact-characterized by low jerk and a single acceleration peak proximal to ball contact-rather than abrupt start/stop motions. Deceleration immediately before contact is strongly associated with distance-control errors (short-putting), whereas excessive late-phase acceleration increases lateral dispersion. Training goals should therefore include producing a controlled acceleration curve that minimizes pre-impact braking while avoiding explosive flaring of the hands.

Practical interventions to shape kinematics and tempo combine motor-learning principles with simple biofeedback. Recommended methods include:

- Metronome-guided practice to engrain target tempo ratios (set beats to align backswing/forward durations).

- Video-based kinematic feedback using high-frame-rate clips to inspect shoulder pivot and wrist angle at transition.

- Inertial-sensor drills that quantify peak acceleration and jerk for objective progression tracking.

- Tempo progression where putt length and tempo are incrementally increased to preserve ratio invariance under varied force demands.

These interventions emphasize external, measurable constraints that accelerate skill acquisition and promote retention.

short Putts and Distance Control: Technique Modifications and Practice Drills for Reliable Lag Putting

Precision on near-range strokes depends on refined biomechanics that prioritize a repeatable arc and consistent contact. Empirical analyses support a low-torque, pendulum-style stroke with restrained wrist flexion to minimize rotational variance at impact. Emphasize a stable core, synchronized shoulder rotation, and a putter path that remains on-plane through the ball. Key technical cues-such as maintaining a slight forward shaft lean and initiating the stroke from the shoulders-produce more consistent launch conditions and reduce side-spin that leads to lips outs.

Small setup modifications yield disproportionate improvements in conversion rates from three to six feet. Adopt a slightly narrower stance, position the ball just inside the lead heel for near-range strokes, and verify eye-position relative to the line to improve alignment consistency. Use targeted drills to ingrain these adjustments:

- Tee Gate Drill: enforces center-face contact and direction.

- Clock Face Drill: varies putter length of strokes to calibrate short-range tempo.

- Coin Roll: refines forward roll by checking first-rotation quality.

These exercises favor constrained repetition and immediate sensory feedback, accelerating motor learning for short-range performance.

For reliable lagging from intermediate distances, structure practice to emphasize tempo preservation and feel under varied conditions. The following compact table provides a progression framework linking drill, objective, and simple performance targets that can be administered on any practice green.

| Drill | Objective | Baseline Target |

|---|---|---|

| 3-6-9 Ladder | Distance scaling and tempo | 80% inside 3ft at each station |

| Two-Touch Drill | Control initial roll & pace | Consistent 1st roll ≤ 6 inches variability |

| Random-Distance Set | Adaptive feel under uncertainty | 60% within designated radius |

Integrate objective measurement and psychological control to consolidate technical gains. Use quantified feedback (make percentage, distance-to-hole averages, first-roll variance) and adopt variable practice schedules to promote transfer to on-course scenarios. Implement a brief, reproducible pre-shot routine emphasizing breath control, one clear target, and a single-word cue to maintain focus. Over time,structured deliberate practice with progressive overload and interleaved variability will increase confidence and reduce performance anxiety on the greens.

Cognitive Strategies Under Pressure: Attentional Focus, Preputt Routines, and Mental Rehearsal Techniques

Contemporary research in motor cognition frames putting success as the product of optimized perception-action coupling under fluctuating arousal. Effective cognitive strategies reduce variability in stroke initiation and tempo by stabilizing the attentional system and automating low-level control processes. Emphasizing an **external locus of attention** (e.g., focus on the intended target line or ball-to-hole trajectory) consistently produces superior motor outcomes compared with internally focused instructions, because external focus promotes efficient neuromuscular coordination and minimizes conscious interference with automated control.

Well-structured pre-shot procedures operate as cognitive scaffolds that constrain decision-making and preserve working memory capacity during execution. A standardized preputt sequence promotes consistency by converting deliberate choices into conditioned action patterns. Typical elements include:

- Visual assessment: read green slope and distance cues.

- Physical calibration: alignment and stance confirmation via a short practice stroke.

- Breath and arousal control: a single exhalation or count to steady sympathetic activation.

- Commitment cue: a word or gesture that signals final intent (e.g., “Smooth”).

When rehearsed deliberately, these components function as an attention offloading routine that lowers the probability of performance breakdown under pressure.

| Imagery Mode | Primary Mechanism | Practical Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Visual | Enhances accuracy of trajectory representation | “See the ball roll into the center” |

| Kinesthetic | Reinforces stroke tempo and feel | “Feel the smooth acceleration” |

| Multisensory | Integrates sight, feel, and rhythm for robust encoding | “Hear the soft roll, feel the follow-through” |

Mental rehearsal-deliberate, modality-specific imagery practiced in low- and high-pressure contexts-strengthens neural rehearsal pathways and increases the probability that the desired motor plan is selected under stress.

Translating cognitive strategies into resilient performance requires deliberate manipulations of attentional focus and arousal during practice. Use narrow-external focus anchors (e.g.,back-of-the-ball spot,hole rim) to minimize attentional shift and adopt a brief “quiet eye” interval immediately before initiation to improve gaze fixation and movement coupling. Under elevated anxiety, implement concise verbal cues and regulated breathing to prevent attentional narrowing or hypervigilance; these countermeasures maintain processing efficiency by stabilizing prefrontal control and reducing catastrophic focus shifts.

To operationalize these techniques in a training plan, integrate progressive pressure exposure with objective metrics and fidelity checks. Sample drills and evaluation criteria include:

- Pressure ladder: incrementally increase consequence (bets, time limits, simulated crowd) while recording made% at 3, 6, 9 feet.

- Routine adherence test: perform 20 putts, score routine compliance and linkage between routine and outcome.

- Mental rehearsal block: 10 imagery trials followed by 10 physical putts,track perceived vividness and execution variance.

Regular measurement of putting percentage, routine consistency, and confidence ratings provides the empirical feedback necessary to refine attentional strategies and ensure transfer from practice to tournament play.

Feedback, Measurement, and Training Design: Using Objective Metrics, Video Analysis, and Distributed Practice to Accelerate Improvement

Reliable improvement requires converting subjective feel into quantifiable outcomes. Adopt a core set of **objective metrics** to track performance across sessions: stroke consistency (standard deviation of putter path), face angle at impact, launch direction, and make-percentage from standardized distances.These metrics enable hypothesis-driven interventions and remove ambiguity when deciding whether a change produced meaningful improvement. Over time, aggregated metrics permit calculation of effect sizes and confidence intervals, which are essential for discriminating noise from true learning.

High-fidelity video analysis functions as the bridge between numbers and motor behavior.Use multi-angle capture (down-the-line and face-on) at ≥120 fps when analyzing short-stroke kinematics, and employ visible anatomical markers to compute joint angles and putter rotation. Software-assisted frame-by-frame review produces two classes of feedback: knowledge of performance (KP)-kinematic descriptors such as shoulder tilt or wrist position-and knowledge of results (KR)-outcomes such as ball roll axis and green speed compensation. Minimize feedback latency by preparing short annotated clips (<10 s) to preserve the athlete's ability to link action with consequence.

Training design should privilege distributed practice and task variability to maximize retention and transfer. Rather than prolonged blocked repetition, schedule short, spaced practice blocks with embedded variability: change putting distance, aim bias, and green slope systematically. Evidence from motor learning indicates that this structure enhances long-term retention despite slower immediate acquisition. Practical implementation can include alternating five-minute precision blocks (near-target) with five-minute variability blocks (mixed distances and breaks) across sessions.

combine metrics and video into concise, actionable training prescriptions. The table below illustrates a simple weekly microcycle that integrates measurement, video review, and feedback modality for three representative drills.Use criterion-based progression (e.g., reduce variability by 10% or reach 70% make-rate) to advance drill complexity.

| Drill | Primary Metric | Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| 3‑ft Accuracy | Make % | KR: immediate score |

| 8‑ft Stroke Path | SD of path (mm) | KP: short video clip |

| speed control | First‑roll distance error (cm) | KR + delayed video |

Iterative evaluation is critical: conduct weekly retention tests (no augmented feedback) and periodic transfer tests on variable greens. Use control charts or simple moving averages to detect trends and apply minimal detectable change (MDC) thresholds before altering the program. Emphasize a feedback hierarchy-first remove systematic errors measurable in objective metrics, then refine technique with targeted KP-while maintaining a schedule of spaced practice (2-3 sessions/week with distributed blocks) to consolidate motor learning.

Equipment and Green Interaction Considerations: Putter Selection, Ball Roll Characteristics, and Adapting to Surface Variability

Optimal putter selection is best understood as a biomechanical and ball-dynamics pairing rather than a purely aesthetic choice. Players should match head shape,mass distribution,and hosel geometry to their habitual stroke arc: high-rotation,arcing strokes frequently enough benefit from toe-hang designs,whereas minimal-face-rotation strokes typically pair with face-balanced models. Equally critically important are effective face loft and shaft length: modest loft (commonly between 2°-4° at address) and a length that promotes a stable shoulder-driven pendulum both reduce face-lift at impact and promote earlier forward roll. Contemporary fitting protocols emphasize matching putter moment of inertia (MOI) to a golfer’s tempo and aim to minimize off-center impact penalties, thereby reducing lateral launch deviations and stochastic variation in putt outcomes.

Key equipment and ball-interaction variables can be summarized for practical fitting and on-course decision-making:

- MOI and weight distribution: Higher MOI increases forgiveness and stabilizes launch after off-center strikes.

- Face loft and texture: Affects initial skid period and time-to-roll; milled faces and specific insert materials alter frictional behavior.

- Head shape and alignment aids: Visual cues influence setup consistency and aim precision.

- Ball construction and cover: Surface roughness and compression influence micro-slip and early roll, especially at low speeds.

Ball-roll characteristics are governed by an initial transient (skid/slide), a transition where the ball begins to grip the turf, and a subsequent pure roll state; reducing the skid duration yields more predictable break and speed control. Empirical fitting and laboratory measures indicate that promoting slight forward rotational launch at impact-through appropriate loft and centered contact-minimizes energy loss to translational skid and reduces sensitivity to minute surface imperfections. Practically, this translates to favoring equipment and impact conditions that shorten the skid phase and produce a stable roll axis, thus improving the repeatability of distance control and line reading.

| Putter Type | Typical MOI | Primary Benefit | Recommended Stroke |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blade | Low-Medium | Precise feel | Slight arc |

| Mallet | High | Forgiveness & stability | Straight/Minimal arc |

| Mid-mallet | Medium-High | Balance of feel & forgiveness | Moderate arc |

Adapting to surface variability demands calibrated sensory input and procedural adjustments.Monitor green speed (Stimp), grain direction, moisture, and temperature pre-round and adapt target speed and launch intent accordingly; on faster surfaces shorten stroke length and soften acceleration, on slower surfaces increase committed forward acceleration. Use targeted practice drills-varying pace, line, and putter type across synthetic and natural surfaces-and, when available, leverage launch monitors to quantify skid duration and launch angle. Emphasize repeatable setup and putter-face control in the pre-putt routine to reduce cognitive load, allowing reliable execution across the stochastic variability inherent in greens.

Q&A

Q: What is meant by an “evidence‑based” approach to putting, and why is it important?

A: An evidence‑based approach integrates peer‑reviewed research from motor learning, biomechanics, vision science and sport psychology with practitioner experience and player preferences. It prioritizes interventions shown to improve accuracy, consistency and learning (retention and transfer) rather than relying solely on tradition or anecdote. This approach helps coaches and players choose techniques and practice methods that produce measurable, reproducible gains and that generalize to on‑course performance.

Q: Which grip styles are supported by empirical evidence as most effective for consistency?

A: experimental and observational work indicates that grips which reduce wrist motion and promote a pendulum‑like stroke tend to increase consistency. Cross‑handed and “left‑hand‑low” variations are associated with reduced wrist breakdown for some players and thus fewer face‑angle errors; tho, there is no single grip universally superior. The best choice is the grip that produces a stable putter face (square relative to the target line through impact) and is comfortable for the player. Importantly, changes should be trialed with adequate practice and assessed for learning and transfer.

Q: What stance and body setup variables influence putting accuracy?

A: Key setup variables supported by research include: a stable base with mild knee flex, a forward bend that allows the eyes to be near or over the ball, and upper body alignment that facilitates a shoulder‑driven stroke. Excessive lateral movement, large forearm rotation, or unstable lower body posture increases variability. Evidence emphasizes consistency of setup across putts (repeatable address position) as a stronger predictor of performance than adherence to any single “ideal” posture.

Q: How should alignment and aim be practiced and evaluated?

A: Alignment should be verified objectively (e.g., using visual markers, alignment sticks, or video) and practiced under varied conditions to avoid overreliance on a single cue. research shows that inaccurate aim is a major source of missed putts; therefore, routine checks of putter face alignment at address and perceptual training for read/aim (including practice with altered visual feedback) improve accuracy.Combining objective checks with pre‑shot routines that include aim verification enhances transfer to competitive settings.

Q: what stroke mechanics lead to repeatable contact and direction control?

A: Biomechanical studies favor a pendulum‑like, shoulder‑dominated stroke with minimal wrist flexion/extension through impact. This reduces putter‑face rotation and variability in launch direction. A smooth, rhythmic stroke with consistent arc and little lateral head movement tends to produce the most reliable outcomes. Players who use excessive hand or wrist manipulation typically show greater dispersion in ball direction.

Q: How important is tempo, and how should players develop it?

A: Consistent tempo is strongly associated with improved distance control and directional consistency. Motor‑learning research suggests that an internally consistent cadence (same rhythm across putts) reduces variability. Training methods include metronome practice, auditory cues, and deliberately practiced rhythmic strokes. Tempo stability should be trained across putt distances and under pressure to ensure robustness.

Q: What does research say about eye position and visual strategies?

A: Studies in vision science and sport performance indicate that keeping the head relatively still and the eyes close to over the ball at address supports accurate putter‑face alignment and stroke monitoring. The “quiet eye” phenomenon – a final,steady visual fixation on the target prior to movement – has been linked to improved accuracy in many precision tasks,including putting. Encouraging controlled visual routines (short fixation on the target/line then on the ball) improves performance, particularly under pressure.

Q: How should players train distance control (speed)?

A: Motor‑learning evidence supports practice that manipulates variability – practicing a range of distances (random/interleaved practice) rather than blocked repetition of a single distance leads to better retention and on‑course transfer. Drills using feedback (e.g., measurement of lag or using a target circle) help calibrate the relationship between stroke length and ball roll. Reduced frequency of immediate corrective feedback (fading KR) often enhances long‑term learning.

Q: What green‑reading strategies are supported by the literature?

A: Objective studies show that perception of slope, grain and speed is error‑prone. Effective strategies include using consistent visual landmarks and combining visual inspection with feel developed through varied practice. Some research supports using a two‑step routine: read the fall at address (including walking the line for subtle cues) and then confirm with a short aim putt to calibrate speed perception. Technology and training aids can speed learning but should be used to develop, not replace, perceptual judgment.

Q: Which practice designs maximize learning and transfer for putting?

A: Contemporary motor‑learning findings favor practice schedules that include:

– Variable practice across distances and slopes (improves transfer)

– Random/interleaved practice rather than prolonged blocked practice (improves retention)

– Appropriate feedback schedules (less frequent immediate feedback, then summary or delayed feedback)

– Mental rehearsal/imagery and focused attention strategies (facilitates consolidation)

– Distributed practice sessions rather than one long continuous session (better retention)

These principles are robust across skill levels but should be adapted to the learner’s stage.

Q: What role do attentional focus and instructions play?

A: A large body of research indicates that an external focus of attention (focus on the effect of the movement, e.g., “focus on the ball rolling to the target”) generally produces better performance and learning than an internal focus (e.g., “keep your wrists still”). Instructions that emphasize outcome and rhythm rather than micro‑technical muscle control lead to more automatic, reliable putting under pressure.

Q: How does psychology and pre‑shot routine influence putting under pressure?

A: Evidence from sport psychology shows that a consistent pre‑shot routine reduces pre‑performance anxiety, stabilizes arousal, and improves focus. Techniques shown to help include quiet‑eye fixation, controlled breathing, concise cue words, and brief mental imagery of a triumphant roll. Emotional regulation strategies (e.g., reappraisal rather than suppression) and practicing under simulated pressure improve competitive robustness.

Q: Do training aids and technology improve putting performance?

A: Training aids (metronomes, alignment guides, mirror devices, launch monitors) can be effective if they target a specific, evidence‑backed deficit and are integrated into a structured practice plan grounded in motor‑learning principles. Overreliance on a device can produce context‑dependent learning; thus, periodic practice without the aid and assessment of transfer to real putts are essential.

Q: Are there biomechanical or equipment constraints to consider (loft, lie, putter fitting)?

A: Equipment characteristics (loft, lie, shaft length, grip size, head balance) influence face contact, roll initiation and feel. empirical fitting that matches putter properties to a player’s stroke (e.g., face‑balanced vs. toe‑hang for different stroke arcs) can reduce corrective movement demands. However, the primary determinant of success remains consistent technique and perceptual‑motor skill; equipment changes should be evaluated for on‑course performance and learning, not only momentary comfort.

Q: What are practical, evidence‑based drills to implement these principles?

A: Examples consistent with the evidence:

– Random distance ladder: place tees at variable distances (3-15 ft) and perform one putt to each location in randomized order to promote variable practice and distance calibration.- Metronome tempo drill: use a tempo cue to establish a consistent rhythm; practice with and without the cue to promote internalization.- Quiet‑eye routine drill: practice establishing a final fixation on the target, then a brief fixation on the ball before stroking.

– Alignment‑feedback drill: use an alignment stick or short mirror for intermittent trials, combined with trials without feedback to encourage transfer.

– Pressure simulation: add performance incentives or crowd noise during practice sets to train psychological resilience.

Q: What are limits of current evidence and directions for future research?

A: Existing research has advanced key principles, but limitations include heterogeneity of study designs, small sample sizes in some biomechanics studies, and limited longitudinal field research showing direct effects on tournament outcomes. Future work should prioritize large‑scale longitudinal trials, individualized responses to interventions (why some players benefit more from a change), and ecology‑valid studies that capture on‑course complexity. Integration of wearable technology and high‑fidelity simulation could improve understanding of how lab findings translate to performance.

Q: What practical guidance can coaches and players take from the evidence?

A: Prioritize interventions that reduce wrist motion and face rotation (pendulum/shoulder stroke),establish a consistent setup and tempo,use an external focus of attention,and practice using variable,randomized schedules with appropriately faded feedback. Develop a concise pre‑shot routine incorporating visual fixation and breathing, and verify alignment objectively. When using training aids or making equipment changes, evaluate transfer to realistic putting tasks and allow sufficient practice for learning to consolidate.

If you would like, I can convert these Q&A items into a printable FAQ for players and coaches, or produce an evidence‑graded checklist for assessment and training sessions.

Closing Remarks

This review has synthesized contemporary empirical evidence across grip mechanics, stance and alignment, stroke kinematics, and cognitive strategies to identify principles that reliably support consistent putting performance. Collectively, the findings emphasize (1) the importance of stable contact and repeatable setup parameters, (2) stroke patterns that minimize needless wrist and hand motion while promoting a consistent pendular action, and (3) cognitive approaches-such as external attentional focus, pre-shot routines, and simplified decision rules-that reduce variability under pressure. Adoption of these evidence-based elements should be tailored to the individual golfer through systematic assessment, monitored practice, and iterative adjustment.

Practitioners and researchers should remain mindful of boundary conditions: individual anthropometrics, green conditions, and situational pressure can moderate the effectiveness of specific techniques. Future work would benefit from longitudinal, ecologically valid studies that integrate biomechanical measurement with outcome metrics and that evaluate cost- and time-efficient training protocols suitable for routine coaching environments. Advances in portable sensing and automated feedback offer promising avenues for translating laboratory findings into field-ready interventions.

In closing, evidence-based putting improvement rests on a cycle of assessment, targeted intervention, and objective feedback.By privileging reproducible setup, biomechanically sound stroke mechanics, and cognitive strategies that enhance focus and decision-making, coaches and players can systematically reduce putt-to-putt variability and improve scoring outcomes. Continued collaboration between scientists and practitioners will be essential to refine these recommendations and to ensure their practical utility across skill levels and competitive contexts.

Evidence-Based Techniques for Improved Golf Putting

Note: the supplied web search results were unrelated to golf; the guidance below draws on established sport-science principles and well-documented putting research (motor learning, quiet-eye research, external-focus findings) to present practical, evidence-based techniques for better putting.

Why an evidence-based approach matters for your golf putting

Putting is a high-precision motor skill that depends on mechanics, perception (green reading), and psychology. Research from motor learning and sports performance consistently shows small, targeted changes-applied with smart practice-produce lasting gains. The goal is consistency: a repeatable setup and stroke that control line and, especially, speed.

Putting fundamentals backed by research

1. Grip and hand position

Consistency in grip wins. Studies and coaching consensus indicate that minimizing wrist movement reduces unwanted rotation and face-angle variability at impact. Popular, research-pleasant grip approaches include:

- Shoulder-dominant grip: hands act as a unit with shoulders driving the pendulum stroke.

- Reverse-overlap or claw variations for players with excessive wrist action.

- Keep grip pressure light and consistent-excess tension reduces feel and smoothness.

Practical: test a lighter grip pressure and a shoulder-lead stroke during practice to compare consistency over 20 repeat putts.

2. Stance, alignment and posture

Stable posture and a consistent address position reduce shot variability. Evidence indicates:

- Shoulder-width stance promotes a stable base for the pendulum motion.

- Slight knee flex and forward-tilt from the hips let the eyes fall over the line-helpful for alignment.

- Align the putter face square to the intended line; use visual aids (alignment sticks, mirror) in training to build a repeatable setup.

3. Stroke mechanics and external focus

Motor learning research (including Wulf and colleagues) shows that adopting an external focus of attention-focusing on the ball’s path or target rather than body parts-improves performance and learning. Practical stroke cues:

- “Send the ball to the center of the cup” (external) rather than “keep your wrists firm” (internal).

- Favor a shoulder-driven pendulum motion with minimal wrist hinge.

- Use rhythm and tempo rather than force-consistent tempo improves distance control.

4. Quiet Eye and focus

Quiet eye research (Vickers et al.) demonstrates that elite performers maintain a longer final visual fixation (the “quiet eye”) before movement initiation. Applied putting tips:

- Pick a small target (edge of the cup or spot 2-3 feet in front of the cup) and hold your gaze for 1-2 seconds before starting the stroke.

- Use a short, repeatable pre-shot gaze routine to settle visual attention and reduce rush.

Green reading and speed control

Line vs. speed – why speed frequently enough wins

Many coaches and studies note that good speed control often saves more putts than perfect line-reading. Putts that miss short or slightly offline are more likely to be made or reduce three-putt risk than putts that reach the hole but roll too fast.

Practical green reading method

- Walk the putt and look for slope patterns, grain and uphill/downhill tempo.

- Visualize the intended starting path and the ball’s pace (fast = flatter line; slow = more break).

- Pick an intermediate aim point (e.g., a blade of grass or patch of lighter turf) rather than “aim at the hole.”

Practice methods rooted in motor learning

Not all practice is equal. Research supports specific practice structures for skill retention and transfer:

- Deliberate practice: short, focused sessions with a single measurable goal (e.g., make 30/50 three-footers).

- Variable practice: mix putts of different lengths and breaks in the same session to improve adaptability on course.

- Interleaved practice (contextual interference): alternating putt types (short, medium, long) leads to better long-term learning than blocked repetition.

- Use immediate, actionable feedback-ball flight and made/missed result are primary KR (knowledge of results); occasional video or coach feedback can provide KP (knowledge of performance).

High-value putting drills (table)

| Drill | Purpose | Time/Set |

|---|---|---|

| Clock Drill | Distance control around the hole, feel | 5-10 minutes |

| Gate Drill | Face alignment & path consistency | 3-5 minutes |

| Distance Ladder | Long putt pace control | 10-15 minutes |

| Quiet-Eye Routine | Pre-shot focus and consistency | daily warm-up |

Detailed drill descriptions and how to use them

Clock Drill (short-range feel)

Place balls at 12 positions around the hole at 3, 6 and 9 feet (or just 3, 6 feet for time-saving). Putt all around the circle; goal to make a set number (e.g.,24/36). This trains consistent speed and reduces anxiety on short putts.

Gate Drill (alignment & path)

Use tees or small cones to create a narrow gate slightly wider than your putter head. putt through the gate without touching the edges-this reinforces a square face and consistent inside-to-square-to-inside arc.

Distance Ladder (long putt pace)

Pick targets at 15, 25, 35, 45 feet. Try to land the ball inside a one-putt zone (e.g., within 3-5 feet) for each target.This builds pace control and reduces three-putts.

Mental strategies and routine

Pre-shot routine

A short, consistent pre-shot routine stabilizes arousal and attention. Key components:

- Visualize the ball path (quiet-eye fixation on aim point).

- take one practice stroke with the exact tempo you want.

- Settle, breathe, and execute-avoid last-second mechanical adjustments.

Confidence, pressure and the yips

Pressure affects motor performance. Use these evidence-based tactics:

- Process goals over outcome goals (e.g., “hit the spot with this tempo” rather than “make it”).

- Simulate pressure in practice with consequences (bets, crowd noise, match play). This improves transfer.

- If you struggle with the yips, try techniques to reduce tension: change grip, shorten backswing, use a long putter, or see a coach/medical professional-yips can have psychological and neurological components and may need specialized help.

Sample evidence-based putting session (45 minutes)

- Warm-up (5 min): short putts (3-5 ft) with quiet-eye holds-focus on routine.

- Gate & alignment work (8 min): 2 sets of 10 putts through gate.

- Clock drill (10 min): 3/6/9 ft rotation-target 80% made.

- Distance ladder (15 min): 15-45 ft targets-goal near 3-5 ft for each.

- Pressure simulation (7 min): match-play format or make/miss streak challenge.

Case study: How a methodical approach cut three putts in half

Player A (scratch to single-digit amateur) struggled with three-putts. Using a structured program-daily 15-minute distance ladder practice, weekly alignment work, and a simplified 6-step pre-shot routine-Player A reduced three-putts by 50% over 8 weeks. Key changes were improved speed control (fewer long putts) and a tighter routine that reduced rushed strokes under pressure.

Checklist: Quick setup audit before every round

- Grip relaxed and repeatable

- Eyes over or slightly inside the ball-line

- putter face square to intended line

- Shoulders and feet aligned to target line

- Quiet-eye target chosen and held briefly

- One practice stroke to set tempo, then execute

Common mistakes and how to fix them

- Too much wrist action: try a heavier putter head or a reverse-overlap/claw grip and focus on shoulder-driven motion.

- Poor tempo: use a metronome app or count “1-2” during practice strokes to establish consistent rhythm.

- Rushing the pre-shot: shorten your routine and lock your quiet-eye fixation to reduce haste.

Putting gear and data-driven practice

Launch monitors and smart putting mats provide measurable feedback on face angle, path, and roll. Use these tools sparingly and focus on key metrics:

- Start-line accuracy (does the ball start on the intended line?)

- Roll quality (topspin/backspin; consistent forward roll)

- Putt dispersion at given distances

Data can accelerate improvements when combined with focused practice goals.

Practical tips to apply on course

- When in doubt, favor a slightly firmer pace to avoid leaving short putts.

- Use a simple, repeatable pre-putt routine to anchor focus under pressure.

- Read the green from behind the ball and also from the low side to confirm break.

- Practice variability-on-course you’ll rarely face identical putts, so train to adapt.

further learning resources

Look for literature on motor learning, Quiet Eye, and external-focus coaching. Working with a certified putting coach and using video feedback accelerates progress.

First-hand experience tip

If your trying to change an entrenched habit, allow a 4-8 week block of deliberate practice with one focused change (e.g., new pre-shot routine or grip tweak). Small, consistent daily work beats one-off long sessions.

keywords: golf putting, putting stroke, green reading, putting grip, putting alignment, putting stance, speed control, distance control, putting drills, putting routine, short game.