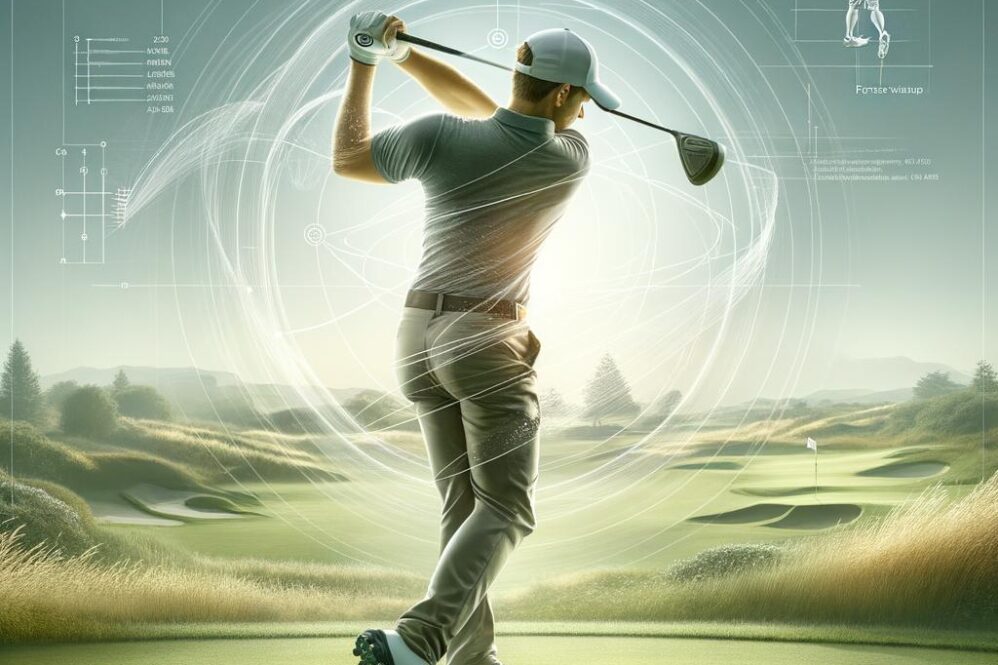

The follow-through phase of the golf swing constitutes more than a cosmetic finish; it encapsulates the culmination of coordinated kinematic and kinetic events that determine ball flight, shot consistency, and musculoskeletal loading.This article examines the biomechanical determinants of an effective follow-through, synthesizing current principles of segmental sequencing, angular momentum transfer, ground reaction force utilization, and clubhead-face control to elucidate how post-impact motion reflects and influences swing efficiency.By framing the follow-through as both an outcome and a diagnostic window into the earlier phases of the swing, the discussion links measurable movement patterns to performance outcomes such as accuracy, dispersion, and repeatability.Drawing on biomechanical theory and applied motor control, the analysis identifies critical elements-timing of proximal-to-distal energy transfer, pelvis-thorax separation, shoulder rotation, wrist dynamics, and weight-shift mechanics-that together optimize energy transfer while minimizing maladaptive loading. Practical implications for training and coaching are considered, including objective markers for video and force-platform assessment, progressions for neuromuscular retraining, and strategies to reduce injury risk without sacrificing performance. The goal is to provide a rigorous, evidence-informed framework that enables players and practitioners to interpret follow-through mechanics diagnostically and to implement targeted interventions that enhance accuracy and precision on the course.

Kinematic Sequencing and Energy Transfer in the Follow-Through: Principles and Coaching Recommendations

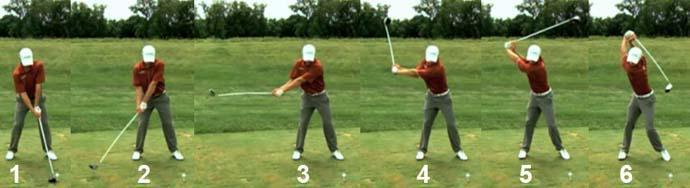

Efficient follow-through is the product of a well-ordered,**proximal-to-distal kinematic sequence** that begins with the ground and pelvis and continues through the trunk,shoulders,arms,and finally the hands and club. In biomechanical terms, optimal sequencing means that each proximal segment reaches its peak angular velocity and begins deceleration slightly before the next distal segment accelerates to its peak; this temporal cascade produces additive segmental velocities at the clubhead. Disruptions to the sequence-early arm acceleration, insufficient hip rotation, or premature trunk deceleration-reduce energy transfer, increase variability at impact, and degrade accuracy and repeatability.

Energy transfer during the follow-through depends on conservation and redirection of angular momentum generated in the downswing.Rather than abruptly stopping at impact, the body continues to rotate so that kinetic energy is smoothly dissipated across segments and through soft tissue. A well-executed follow-through therefore displays a graded reduction in segmental angular velocities: the hips slow first, followed by the torso and shoulders, with the arms and club decelerating last. This controlled dissipation preserves clubhead speed through impact while preventing excessive stress concentrations across joints.

Controlled deceleration relies on eccentric muscle actions and coordinated joint loading to absorb residual energy safely. Key muscular contributors include the hip rotators and extensors, the oblique and erector spinae groups for trunk control, and the shoulder girdle and elbow flexors for arm deceleration. Proper sequencing reduces peak joint moments; conversely, poor timing forces individual muscles to absorb disproportionately large loads, increasing risk of overuse injury. From a performance perspective, the follow-through should be assessed for symmetry, rhythm, and absence of abrupt halting motions-markers of inefficient energy transfer.

Coaching interventions should target timing, feel cues, and progressive overload of the kinetic chain. Recommended practice elements include:

- Drills: slow-motion sequencing drills, step-and-swing to emphasize ground-to-pelvis initiation, and towel-under-arm to maintain connection.

- Checkpoints: steady weight transition to lead foot, continued shoulder rotation after impact, and relaxed wrist release.

- Progressions: rhythm-focused metronome practice, then incremental speed increases while maintaining sequence integrity.

| Segment | Primary Role in Follow-Through | Coaching cue |

|---|---|---|

| Hips | Initiate deceleration, transfer momentum | “Rotate through the target” |

| Torso | Transmit angular momentum | “Turn, not stop” |

| Arms/Hands | Fine-tune clubface and absorb residual energy | “Release and hold the finish” |

these recommendations emphasize measurable, repeatable sequencing cues that coaches can use to restore efficient energy transfer and enhance shot consistency.

Pelvic and Thoracic Rotation alignment for Consistent Ball Flight: Biomechanical Insights and Corrective Strategies

Segmental coordination of the pelvis and thorax is a primary determinant of repeatable launch conditions in the follow-through.Kinematic sequencing that begins with controlled pelvic rotation, followed by timely thoracic rotation, produces a stable distal release and reduces lateral variability at impact. Pelvic stability is supported not only by hip and trunk musculature but also by the pelvic floor complex; clinically this region comprises approximately 26 muscles, forming a dynamic base for intra‑abdominal pressure modulation and load transfer during rotation. Optimizing the interaction between pelvic and thoracic rotations thus reduces compensatory wrist and arm motions that generate unwanted sidespin and dispersion.

Common alignment faults produce characteristic flight patterns and can be targeted with specific mechanical corrections. Typical errors include anterior pelvic tilt with reduced transverse rotation (leading to loss of distance and low launch) and over‑dominant thoracic rotation uncoupled from the pelvis (increasing side spin). Practical corrective emphases include:

• Pelvic drive normalization – cue a directed lateral rotation toward the target while maintaining neutral pelvic tilt;

• Thoracic follow‑through control – emphasize scapular retraction and controlled extension rather than excessive lateral flexion;

• Sequencing drills – rehearsal of pelvis‑first drill patterns to restore the intended kinematic chain.

Rehabilitation‑informed interventions augment performance coaching by addressing deep stabilizers and mobility constraints.Pelvic floor and core activation drills (adaptations of evidence‑based pelvic floor physical therapy and targeted Kegel progressions) improve the feedforward stabilization required for consistent pelvic rotation.Concurrently, thoracic mobility routines (foam‑roller thoracic extensions, controlled segmental rotations) increase safe rotational capacity. Program variables should be prescribed with progressive overload: 3-4 sessions/week, 2-4 stability/motor control drills per session, and mobility work incorporated into warm‑up and post‑practice recovery.

quantifiable coaching cues and measurement targets facilitate transfer to the course: aim for a reproducible pelvis‑to‑thorax rotation ratio that creates a measurable separation (pelvis rotation initiating ~40-50% of the total transverse rotation, thorax completing the remainder) and minimizes compensatory distal adjustments. Use video analysis and simple inertial sensors to monitor phase timing and angular velocity; biofeedback that rewards pelvis‑first sequencing reduces shot dispersion.In practice, concise cues such as “rotate hips to start, let chest follow” combined with targeted stability drills produce measurable improvements in launch consistency and lateral accuracy.

Wrist and Forearm release Mechanics: Optimizing Clubface Control with Targeted Drills

Precision in the terminal phase of the stroke depends on coordinated wrist and forearm kinetics: a controlled transition from stored elastic energy to a timed release governs clubface orientation through impact. Anatomically, the carpus comprises eight carpal bones forming multiple articulations that permit sagittal (flexion/extension), frontal (radial/ulnar deviation) and transverse (pronation/supination) motions; these coupled degrees of freedom require modulation rather than maximal excursion to maintain face control. from a biomechanical perspective, optimal release is characterized by a smooth, distal-to-proximal energy transfer with minimal late-stage compensatory wrist collapse; this pattern aligns the clubhead plane and stabilizes face angle in the critical milliseconds around impact.

Neuromuscular contributors include the flexor-pronator mass, wrist extensors, and the supinator/pronator groups of the forearm. Strength, endurance and intramuscular coordination of these units determine the ability to decelerate and then redirect rotational energy without inducing harmful shearing or compressive loads at the wrist joint. Clinically relevant observations from wrist pathology literature indicate that repetitive high-velocity loading and maladaptive kinematics increase the risk of tendinopathy, sprain or overuse syndromes; thus, any training progression must balance load exposure with recovery and mobility work to mitigate injury risk.

Targeted drills train timing, proprioception and the specific muscle synergies that modulate face rotation. recommended exercises include:

- Slow-Motion Release with Impact Bag – exaggerate the release rhythm to ingrain distal-to-proximal sequencing and immediate feedback on face orientation.

- Toe-Up / Toe-Down Wrist Drill – oscillate the clubhead through the top of the swing to train forearm pronator/supinator timing relative to forearm rotation.

- Wrist-Roller Strength Sets – concentric/eccentric loading for flexors and extensors to improve deceleration capacity.

- Split-Hand tempo Swings - alter leverage to emphasize forearm control and reduce dominant-hand overactivity.

Each drill emphasizes a single mechanical objective (timing, strength, proprioception, or lever reduction) to produce transfer to on-course face-control demands.

Programmatic progression and objective feedback accelerate consolidation: begin with low-load,high-sensory drills and progress to full-speed dynamic practice as tolerability permits. Use objective markers (video frame analysis,impact tape,or launch monitor face-angle readings) and subjective pain/function scales to gauge readiness. A concise practice microcycle is provided below for practical implementation; escalate volume by no more than 10-15% weekly and consult a clinician if persistent pain or functional loss occurs (wrist pain etiologies often require targeted evaluation and management).

| Drill | Target | Weekly Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Slow-Motion Impact Bag | timing & face feel | 3×10 reps |

| Toe-Up / Toe-Down | Pronation timing | 3×20 swings |

| Wrist-Roller | Flexor/extensor strength | 3 sets, 2×/week |

| Split-Hand Tempo | Lever control | 4×10 swings |

Lower Limb Contribution and Balance Maintenance During Follow-Through: Stability Techniques for Improved Accuracy

The lower limbs act as the primary interface between the golfer and the ground, mediating transfer of energy and controlling the centre of pressure (COP) trajectory throughout the swing. Efficient follow-through depends on a coordinated sequence of hip extension, knee stabilization and ankle stiffness that together manage ground reaction forces (GRF). When the lower body successfully arrests residual rotational momentum post-impact,it reduces unwanted lateral sway and rotational variability at the torso and upper limbs,thereby improving shot dispersion and repeatability. Emphasizing **controlled deceleration** of the rear leg and progressive weight migration to the lead side produces a more predictable COP pathway and stabilizes the clubhead through release and beyond.

Technical interventions that enhance this stability are best framed as neuromechanical adjustments rather than isolated strength prescriptions. Key modifications include optimizing **stance width** to balance rotational freedom with base-of-support, maintaining moderate **knee flexion** to engage elastic recoil mechanisms, and encouraging slight **lead-side load** during the early follow-through to prevent posterior collapse. Effective, evidence-informed drills include:

- Split-stance holds – isometric holds at impact position for 3-5 seconds to reinforce post-impact stability.

- Single-leg balance with club – eyes-open/closed progressions to enhance proprioceptive control under rotational perturbation.

- Medicine-ball rotational throws – timed to mimic the deceleration phase and develop eccentric hip control.

- Eccentric calf control – slow lowering from heel raise to improve ankle dorsiflexion stability during COP transition.

Neuromuscular timing is critical: EMG-pattern analogues show that proximal hip extensors and gluteal musculature must activate slightly earlier and sustain longer during the follow-through than distal stabilizers to preserve trunk alignment. Training should therefore target both feedforward activation (anticipatory postural adjustments) and feedback-driven corrections (reactive balance). The following concise table highlights primary lower-limb contributions across swing epochs and can guide targeted interventions.

| Swing Epoch | Primary Lower-Limb Action | Targeted Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Downswing → Impact | Lead-leg load, hip extension | Stable platform for club transfer |

| Early Follow-Through | Deceleration via rear-leg eccentric control | Reduced torso rotation variance |

| Late Follow-Through | Weight settlement on lead limb | Consistent COP endpoint |

Coaching cues should translate biomechanical aims into concise, actionable instructions-for example, **”settle onto the lead foot after impact”**, **”feel the rear glute brake rotation”**, or **”maintain a soft lead knee through finish.”** Objective monitoring (e.g., COP displacement, time-to-stabilization, shot dispersion) enables measurable progress: reductions in COP travel distance and a shorter time-to-stabilization after impact correlate with decreased lateral miss rates. Integrating stability work into on-course routines-progressing from slow, controlled drills to full-speed swings-ensures transfer of neuromuscular adaptations into improved accuracy and repeatability under competitive constraints.

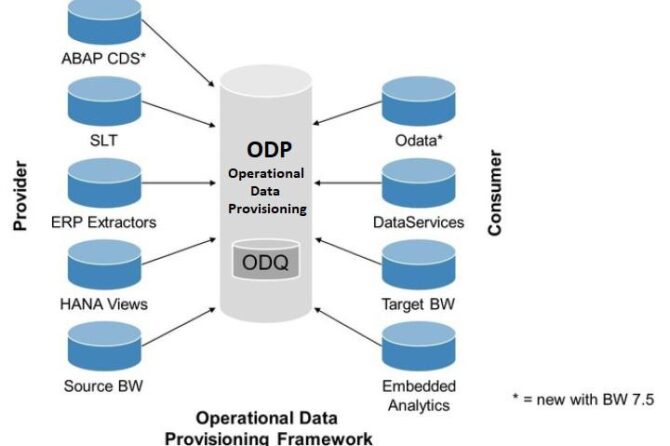

Temporal Coordination and Tempo Regulation: Measuring and Training Effective Follow-Through Timing

Temporal coordination in the swing is the orchestrated sequencing of segmental actions that produces a repeatable follow-through. Precise ordering – pelvis rotation, thorax opening, arm extension, wrist unhinging and clubhead passage – determines the timing window through which impact is achieved and the subsequent follow-through trajectory emerges. Contemporary measurement techniques permit objective quantification of these events: high‑speed video (250-1000+ fps) captures discrete kinematic events; inertial measurement units (IMUs) provide time‑stamped angular velocity profiles; pressure‑sensing plates reveal weight‑transfer timing; and Doppler radar or launch monitors furnish clubhead velocity traces. Interpreting temporal offsets (e.g., milliseconds of delayed wrist release) is essential to diagnosing causal links between timing perturbations and shot dispersion.

Temporal metrics translate to training targets when expressed as simple, comparable indices.Commonly used indicators include the backswing:downswing duration ratio, time-from-transition-to-impact, and the duration of deceleration after impact. The table below summarizes practical metrics and normative targets that are useful in clinical coaching and research contexts.

| Metric | Definition | Practical Target |

|---|---|---|

| Backswing:Downswing | Duration ratio from address to top vs. top to impact | ~3:1 (range 2.5-3.5) |

| Transition latency | Time from lowest centre‑of‑mass to peak pelvis rotation | 30-60 ms |

| Impact‑to‑finish | Time from ball contact to stabilized finish | 300-700 ms (club‑dependent) |

Training interventions should target both tempo regulation and the variability of timing events. Evidence‑based drills include: metronome pacing to establish a global tempo, segmental isolation (e.g., lower‑body lead drills) to refine intersegment delays, and external‑focus tasks (targeted accuracy constraints) to stabilize timing under performance pressure. Example practice emphases are provided in the list below,each promoting different aspects of temporal control.

- Metronome pacing: set beats for address, top, and impact to compress or expand tempo

- Segmental delay drills: practice delaying arm release while maintaining pelvic rotation

- Tempo ladder: perform swings at incremental tempo steps to map performance vs. timing

- Variable practice: randomize club selection and target distance to increase robustness of timing patterns

For applied coaching, implement longitudinal monitoring and individualized thresholds: establish a baseline temporal profile, define acceptable within‑session variability (e.g., coefficient of variation <10% for key timings), and apply progressive overload of temporal constraints. Integrate objective feedback (IMU traces,video slow‑motion,auditory metronome) within a closed feedback loop so athletes can iteratively adjust. Ultimately, enhancements in follow‑through timing should manifest as reduced lateral and longitudinal dispersion - linking temporal control directly to measurable gains in accuracy and consistency.

Ground Reaction Forces and Weight Shift Patterns: Evidence based Conditioning and Practice Protocols

Contemporary biomechanical frameworks characterize the follow-through as the phase during which the golfer dissipates residual kinetic energy and stabilizes the system for repeatable outcomes. Ground reaction forces (GRFs) function as the primary external impulse exchanged between the body and ground; their vertical and shear components govern launch conditions, whereas the medial-lateral and anterior-posterior vectors influence clubface control during release. Drawing on essential definitions of biomechanics,GRF analysis links force-time characteristics to tissue loading and motor control strategies,making it possible to translate laboratory measures into practical coaching cues such as controlling center-of-pressure (CoP) migration and minimizing late lateral loading that destabilizes the finishing posture.

Weight transfer is not a monolithic event but a sequenced redistribution of mass and force that should satisfy both performance and injury-minimization objectives. Evidence-based conditioning emphasizes the coordination of hip and trunk rotation with timely lateral-to-medial GRF transfer to optimize energy flow through the kinetic chain. Core elements for targeted conditioning include:

- rate of force development training to shorten time-to-peak GRF during transition and impact.

- Single‑leg stability to control CoP excursion through the lead foot in the follow-through.

- Rotational power to couple pelvic deceleration with upper-torso recoil.

- Mobility control for ankle, hip, and thoracic segments to permit efficient weight shift without compensatory shear loads.

Practice protocols should progress from isolated, coach‑led motor patterning to integrated, tempo-constrained scenarios with objective load feedback. Starter drills include slow‑motion weight transfer sequences with pauses at impact,unilateral balance tasks on compliant surfaces,and submaximal overspeed swings to train neuromuscular timing. The following table provides a concise practice progression that links drill, primary GRF-related target, and recommended dosage for field use:

| Drill | primary Metric | Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Pause at Impact | CoP stability / time-to-peak | 3 sets × 8 reps, 2s pause |

| Single‑Leg Holds | Medial GRF control | 3 sets × 30s each leg |

| Med Ball Rotations | Rotational power transfer | 4 sets × 6 reps, explosive |

Monitoring and progression require objective feedback to ensure protocols produce the intended GRF and weight‑shift adaptations. Laboratory-grade force plates remain the gold standard for capturing peak forces,impulse,and CoP trajectories,while wearable pressure insoles and inertial sensors afford field-usable proxies. Coaches should track a small set of repeatable metrics-peak vertical GRF ratio (lead:trail), time-to-peak around impact, and CoP displacement in the lead foot-and use them to guide load increments and drill complexity. Practical implementation favors a cycle of measurement, targeted conditioning, and constrained practice (tempo, stance width, and ball position) to embed efficient weight-shift patterns into the golfer’s follow-through mechanics.

Integrating Biomechanical Feedback into Practice: Motion Analysis, Objective Metrics and Progressive Training Plans

The submission of modern motion-capture and wearable technologies permits a quantitative reconstruction of the follow-through as a coordinated, multi‑segment event. High‑speed video (200+ fps) and markerless 3D systems yield kinematic time‑series that reveal sequencing errors (e.g.,early arm release,delayed pelvis rotation),while inertial measurement units (IMUs) and force platforms provide complementary kinetic data such as angular velocity profiles and ground reaction force (GRF) vectors. Establishing a laboratory or on‑course baseline with synchronized kinematic and kinetic recordings is essential: it delineates an athlete‑specific normative window and reduces reliance on subjective cues during coaching interventions.

Objective metrics translate biomechanical observations into actionable targets. Key variables include clubhead speed, pelvis‑to‑shoulder separation angle, peak trunk angular velocity, lead‑leg braking impulse, and tempo ratio (backswing:downswing). Below is a concise reference table for commonly used metrics and pragmatic target ranges drawn from applied biomechanics literature and elite performance norms.

| Metric | Interpretation | Representative Target |

|---|---|---|

| Clubhead speed | Proxy for energy transfer efficiency | Variable by athlete; +/− 5% baseline |

| Pelvis‑shoulder separation | Indicator of X‑factor and elastic energy storage | 20°-40° at top of backswing |

| Peak trunk angular velocity | Relates to rotational power | Increase progressively by 5-10% |

| Lead‑leg braking impulse | Controls deceleration and balance | Consistent within session; low variance |

Translation of assessment into a progressive plan requires staged objectives, objective monitoring and targeted interventions.typical phases include: (1) mobility and neuromuscular control to correct positional constraints; (2) strength and power development emphasizing rotational force couples and eccentric control; (3) motor‑pattern reinforcement using augmented feedback; and (4) transfer to on‑course variability under fatigue. Effective practice sessions embed brief, focused feedback loops-video clips with overlaid kinematic traces, auditory tempo cues, and IMU‑derived performance scores-and employ an evidence‑based progression criterion (e.g., two consecutive sessions within target metric ranges) before increasing load or complexity. Practical drills should be selected to address the specific metric deficits identified in the baseline analysis.

Q&A

Note: the provided web search results did not contain materials relevant to golf biomechanics.The following Q&A is therefore an original, academically styled synthesis of biomechanical principles and coaching practice relevant to the golf swing follow-through. For practical application, readers should consult primary biomechanics literature and sport-science resources.

Q1: What is the follow-through in the context of the golf swing and why is it biomechanically significant?

A1: The follow-through is the post-impact phase of the golf swing that begins immediately after ball/club contact and continues until the swing terminates (commonly a balanced “finish” position).Biomechanically, it represents the expression of momentum, energy transfer, and neuromuscular deceleration that result from the pre-impact kinematic sequence. A technically sound follow-through reflects correct proximal-to-distal sequencing, efficient energy transfer, controlled deceleration of body segments, and appropriate clubface orientation at impact – all of which underpin repeatable accuracy and precision.

Q2: How does the follow-through relate to the kinematic sequence of the swing?

A2: The kinematic sequence describes the timed activation and angular velocities of body segments from pelvis to trunk to shoulders to arms and club (proximal-to-distal).A correct kinematic sequence produces optimal clubhead speed and controlled release. The follow-through is the terminal manifestation of this sequence: it must accommodate the residual angular momentum and facilitate controlled dissipation of energy via eccentric muscle actions.Disruptions in the sequence (e.g., early arm-dominant motion) will appear as abnormal follow-through positions and correlate with poorer impact conditions.Q3: Which biomechanical variables during the follow-through most strongly influence accuracy and precision?

A3: Key variables include:

– Clubface orientation trajectory through impact and into the follow-through (predictor of ball direction).

- Rotational speed and timing of pelvis and thorax (predictors of consistency).

– Plane and path of the club shaft (affects curvature and dispersion).

– Ground reaction force (GRF) patterns and weight transfer (affect balance and repeatability).

– Timing and magnitude of eccentric muscle activity during deceleration (affect joint control and shot dispersion).

Q4: What role do ground reaction forces play in the follow-through?

A4: GRFs provide the external forces that permit generation and transfer of angular momentum. During the downswing and follow-through, the pattern of vertical and horizontal GRFs – especially timely lateral-to-medial force on the trail foot and a front-foot loading at impact - supports stable base of support, effective weight transfer, and balanced deceleration. Abnormal GRF patterns can lead to excessive sway or loss of balance, degrading accuracy.

Q5: How does proximal-to-distal sequencing affect the clubface at impact and in the follow-through?

A5: Correct proximal-to-distal sequencing creates a progressive transfer of angular velocity from large to small segments, culminating in high clubhead speed while maintaining predictable face orientation. If sequencing is premature or reversed (e.g., “casting” with early wrist release), the clubface orientation and release timing become inconsistent, producing erratic follow-through positions and larger dispersion.

Q6: Which joints and muscle groups are most active during the follow-through, and what are their roles?

A6: Primary contributors include:

– Hips/pelvis: rotational deceleration via gluteal and hip rotators; control weight transfer.

– Trunk/obliques: control torso rotation and deceleration; maintain posture.

– Shoulders and scapulothoracic muscles: guide arm path and stabilize scapula during follow-through.

– Elbow extensors/flexors and forearm pronators/supinators: control the release and clubface rotation.

- Lower-limb musculature (quadriceps, hamstrings, calves): contribute to GRF generation and balance.

Q7: What are common follow-through faults and their probable biomechanical causes?

A7: Common faults and correlates:

– Early finish with lack of rotation (open or closed finish): limited hip rotation or insufficient trunk mobility; early deceleration.

- over-the-top/steep follow-through: poor swing plane control, lateral sway, or early upper-body rotation.

– Casting (flat finish, lack of lag): premature wrist release, weak distal sequencing.

– Falling back or loss of balance in finish: inadequate weight transfer, poor GRF pattern, weak lower-limb stabilization.

Q8: How can clinicians and coaches objectively assess the follow-through?

A8: Objective assessment tools include: high-speed video (sagittal and down-the-line views), 3D motion capture for kinematics, force plates for GRF analysis, wearable IMUs for segmental angular velocity, and launch monitors to correlate impact conditions with follow-through. Key metrics to record: pelvis/thorax rotation angles and velocities, clubhead path and face angle, weight distribution, and finish position symmetry.

Q9: Which drills specifically target a biomechanically effective follow-through?

A9: Effective drills:

– Pause-at-impact drill: slow to impact and hold the position briefly to reinforce correct alignment and sequencing.

– One-arm follow-through drill (trail arm): promotes correct release and reduces compensatory shoulder motion.

– Step-through drill: exaggerates weight transfer into the lead foot, promoting balance and rotation.

– Impact-bag or towel-under-arms drill: stabilizes torso-arm connection to encourage correct sequencing.

- Slow-motion repeats with video feedback: reinforces motor patterns and timing.

Q10: What coaching cues are most consistent with biomechanical principles to improve follow-through?

A10: Effective cues are short, external-focus, and emphasize outcome or feel rather than micro-instruction. Examples:

– “Rotate the hips through the shot” (promotes proximal rotation).

– “Finish tall and balanced facing the target” (promotes controlled deceleration).

– ”Let the club wrap around your body” (encourages proper release path).

– “Step into the lead foot” (promotes weight transfer and GRF utilization).

Q11: How does club selection (e.g., driver vs. wedge) influence ideal follow-through biomechanics?

A11: Club length,loft,and intended swing speed alter optimal kinematics. Longer clubs and higher speed (drivers) require greater proximal-to-distal sequencing and longer release phases; the follow-through tends to be more extended and pronounced. Shorter clubs and steeper attack angles (wedges) demand tighter rotation and earlier deceleration to control trajectory and spin; follow-through may be more compact. However, core principles-sequencing, balance, and controlled deceleration-remain consistent across clubs.Q12: What role does the follow-through play in injury risk and longevity?

A12: An uncontrolled or abrupt follow-through can increase eccentric loading on lumbar spine, shoulders, and wrists. Repeated compensatory movements (e.g., decelerating via the lead arm or excessive lumbar extension) can elevate injury risk. Proper follow-through that emphasizes balanced deceleration, distributed loading across large muscle groups, and adequate mobility reduces repetitive strain and supports long-term musculoskeletal health.

Q13: How should training load and conditioning be integrated to support an improved follow-through?

A13: conditioning should target rotational strength, trunk stability, hip mobility, and eccentric control. Progressive overload principles apply: begin with mobility and neuromuscular control, advance to rotational power exercises (medicine ball throws), and include eccentric training for posterior chain and shoulder stabilizers. Monitor volume and fatigue as swing mechanics degrade with fatigue, increasing follow-through variability.

Q14: How can one quantify improvements in accuracy and precision after follow-through-focused training?

A14: Use repeated trial testing with launch monitors or range sessions, recording directional dispersion (standard deviation of carry direction), lateral dispersion, clubface angle consistency at impact, and carry distance variability. Compare pre- and post-intervention statistics (e.g., mean bias, standard deviation) under controlled conditions. Video/kinematic measures (improved sequencing timings, consistent finish angles) provide mechanistic confirmation.

Q15: Are there population-specific considerations (e.g., older golfers, juniors) for follow-through training?

A15: Yes. Older golfers often have reduced trunk rotation and hip mobility; training should prioritize mobility and controlled strength rather than high-impact power drills. Juniors may require phased motor learning emphasizing movement patterns and play-based repetition. Individualization is critical: modify drills, volume, and intensity according to developmental stage, mobility, and injury history.

Q16: What research methods are commonly used to study follow-through biomechanics?

A16: Methods include 3D motion capture (marker-based or markerless) for kinematic analysis, force plates for GRF, electromyography (EMG) for muscle activation patterns, inertial measurement units (IMUs) for field-based angular velocity, and ball-tracking systems for performance outcomes. Experimental protocols often combine these modalities to link kinematics/kinetics with impact conditions and shot outcomes.

Q17: Can focusing on the follow-through alone correct swing errors originating earlier in the swing?

A17: No – the follow-through is largely an outcome of pre-impact mechanics. While practicing a proper follow-through can provide proprioceptive feedback and help engrain correct sequencing,persistent faults that originate in address,backswing,or transition generally require upstream corrective work. Effective coaching integrates follow-through training with earlier-phase technical adjustments.

Q18: What are recommended next steps for a coach or practitioner seeking to implement follow-through biomechanical training?

A18: Recommended steps:

– Baseline assessment: record video and, where possible, instrumented metrics (IMU/force plates).

– Identify primary mechanical deficits (sequencing, rotation, GRFs).

– Design a targeted intervention combining drills, strength/mobility work, and feedback devices.

– Implement progressive training with objective monitoring (launch data, dispersion metrics).

– Reassess and iterate, prioritizing transfer to on-course performance.

Q19: How should findings from biomechanics be communicated to golfers to maximize adoption?

A19: Translate biomechanical findings into concise, actionable cues and drills; use visual feedback (video overlay) and simple metrics (e.g., dispersion changes). Emphasize measurable benefits (improved consistency) and keep instructions limited to one or two changes per session to avoid cognitive overload.Q20: Where can readers find further authoritative resources on golf biomechanics and motor learning?

A20: Recommended sources include peer-reviewed journals in sports biomechanics and medicine (e.g., Journal of Applied Biomechanics, Sports Biomechanics, Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise), textbooks on swing mechanics, and applied research from university golf-science programs. The article that prompted this Q&A provides applied context; practitioners should supplement with primary research and professional coaching certification materials.

if you would like, I can:

– Convert these Q&As into a printable FAQ for coaches or players.

- Produce a short practical coaching plan (4-8 weeks) that targets follow-through improvements with drills and conditioning.

– provide annotated references from peer-reviewed literature on kinematic sequencing and follow-through mechanics.

a biomechanically informed approach to the golf swing follow-through illuminates how coordinated multi‑segmental motion, timely energy transfer, and effective deceleration jointly determine shot accuracy and precision. Key elements-an optimal kinematic sequence (proximal-to-distal activation), controlled release of wrist hinge, maintained postural alignment, and appropriate management of ground reaction forces-facilitate a repeatable clubhead path and consistent clubface orientation at impact.Conversely, breakdowns in sequencing, balance, or deceleration increase variability and the likelihood of misdirection or distance loss.Practically, these insights translate into targeted interventions for players and coaches: emphasize drills that reinforce the correct kinematic sequence and rhythm, incorporate balance and lower‑body stability exercises, use video and sensor‑based feedback to monitor clubhead and segmental timings, and adopt progressive overload and mobility work to preserve safe deceleration mechanics. Attention to finish position-balanced, facing the target, with controlled torso rotation-serves both as an indicator of technical fidelity and as a safeguard against chronic overload injuries.

Limitations of current applied practice include interindividual variability in anatomy and preferred swing archetypes,and the need for more longitudinal and ecological studies linking specific follow‑through patterns to on‑course performance outcomes. Future research should integrate motion capture, force plate, and muscle activity data across diverse player populations to refine prescriptions that are both performance‑enhancing and injury‑preventive.

Ultimately, mastering the follow‑through is not an isolated aesthetic goal but an evidence‑based strategy to consolidate energy transfer, stabilize the clubface, and produce predictable ball flight. By combining biomechanical principles with individualized assessment and systematic practice, golfers and coaches can meaningfully improve accuracy, precision, and longevity in performance.

mastering the Golf Swing Follow-Through: Biomechanics

Why the follow-through matters for precision and consistency

The follow-through is not just a cosmetic finish to a golf swing – it’s a measurable outcome of how well you sequenced your swing, balanced ground forces, and transferred energy through the club to the ball. A repeatable follow-through correlates strongly with ball striking, clubface control, and reduced shot dispersion. Understanding the biomechanics of the follow-through helps golfers of all levels improve accuracy, distance control, and consistency on the course.

core biomechanical principles that shape the follow-through

- Proximal-to-distal sequencing: Efficient swings transfer energy from large segments (hips and torso) to smaller ones (arms, wrists) and finally to the clubhead. Proper sequencing continues into the follow-through, indicating efficient energy transfer through impact.

- Ground reaction forces (GRF): Force applied to the ground creates an equal and opposite reaction that helps generate clubhead speed. How you shift and stabilize weight through impact affects the follow-through position and balance.

- Angular momentum and rotation: The torso and hips generate rotational velocity; the follow-through shows whether rotation decelerated properly or was blocked (leading to compensations at the arms).

- Center of mass control: Maintaining a controlled center of mass ensures stability in the follow-through.Excess moving of the center causes inconsistent contact and ball flight.

- Deceleration vs. acceleration: The club must decelerate after impact; an aggressive or uncontrolled deceleration will show up as an abrupt or off-balance follow-through.

Key follow-through positions: what to look for

Use these biomechanically sound checkpoints to evaluate and reproduce a quality follow-through:

- Balanced finish: Weight predominantly (but not fully) on the lead foot, with the trail foot’s heel off the ground in many swings – shows proper weight transfer.

- Chest and belt facing the target: Torso rotated toward the target; shoulders and hips rotated through impact indicating full rotation.

- Arms relaxed and extended: Arms should be extended but not locked; the club over or slightly behind the lead shoulder depending on club and shot shape.

- Stable head position: Head has moved slightly toward the target (natural), but remains in control – excessive lateral head movement indicates poor balance.

- Club shaft angle: For irons, shaft typically points at or over the lead shoulder; for full driver swing the finish may be higher but still balanced – useful visual cue for consistency.

Common follow-through faults and biomechanical causes

Below is a speedy reference table with common faults, their likely biomechanical cause, and an immediate drill or fix you can practise.

| Fault | Likely biomechanical cause | Quick fix / Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Falling back or losing balance | Poor weight transfer; late hip rotation | Step-and-drive drill: step to lead foot and hold finish |

| Arms collapsing through finish | early release; lack of torso rotation | Wall drill: limit hand release, rotate torso fully |

| Over-rotated upper body (chest too open early) | Upper-body driven swing; unsupported hips | Hip-lead drill: initiate downswing with hips first |

| Low or flat finish | insufficient clubhead speed or blocked rotation | Tempo drill with towel under arms to keep connection |

Drills to build a consistent, biomechanically sound follow-through

consistent practice with targeted drills builds muscle memory for the correct sequencing and balance. Here are high-value drills that address the most common follow-through issues.

1. Step-through Drill (weight transfer & balance)

- Address the ball normally. Take your regular backswing and begin the downswing. As you move through impact, take a small step forward with your trail foot so it lands near or ahead of the lead foot.

- Hold the finish for 3-5 seconds, checking for chest rotation and balanced weight on the lead foot.

- Benefits: reinforces proper lateral weight shift and balanced finish, reduces sway.

2. Medicine Ball Rotation (power & sequencing)

- Use a light medicine ball or rotational cable.Simulate the golf swing path while focusing on initiating movement from the hips and letting the arms follow.

- Perform controlled, explosive rotations, and stop in the finish position – feels like the torso led the motion into the follow-through.

- Benefits: reinforces proximal-to-distal sequencing and improves rotational power.

3. Towel under armpits (connection & synchronized movement)

- Place a small towel under both armpits and swing while keeping the towel in place. This helps maintain the correct relationship between arms and torso.

- Finish by checking that both the towel and chest rotate to the target together.

- Benefits: prevents arm-dominant swings and maintains swing plane into the follow-through.

4. Slow-motion mirror drills (position feedback)

- Practice the full swing in slow motion in front of a mirror. Pause at impact and at your finish to inspect angles of the shoulders, hips, and club.

- Use video capture to compare swings over time – small changes compound into big consistency improvements.

Mobility and strength training for a safer, stronger follow-through

Biomechanics are limited by mobility and strength. targeted mobility and stability work will make it easier to reach and hold a balanced finish.

Mobility focus areas

- Thoracic rotation – helps achieve chest-open finish without compensating with the shoulders.

- Hip internal/external rotation – essential for smooth weight transfer and full hip clearance.

- Ankle dorsiflexion and stability – supports a stable base and prevents excessive sway.

Strength & stability exercises

- Single-leg Romanian deadlifts – improve single-leg stability for better balance in the finish.

- Pallof press – builds anti-rotation strength, helping control torso during the follow-through.

- Rotational cable chops – train explosive rotation and the proximal-to-distal sequencing used in the swing.

Practical practice routine: 6-week progression to improve your follow-through

Structured practice beats random hitting. Try this weekly framework to engrain biomechanically sound follow-through patterns.

- Weeks 1-2: Mobility + slow-motion swings (3× per week). Emphasize thoracic rotation and hip mobility. Use mirror and video feedback.

- Weeks 3-4: Introduce drills (step-through, towel under armpits) and medicine ball rotations (2-3× per week). Range sessions: 45-60 minutes focusing on 60-80 quality shots per session.

- Weeks 5-6: Add strength and stability training (2× per week) and full-speed swings under supervision.Begin on-range shot-shaping and simulated course play while maintaining finish checkpoints.

How to measure progress: objective markers to track

- Shot dispersion (landing area): narrower dispersion indicates more consistent clubface control and follow-through.

- Video analysis: measure shoulder/hip rotation angles and weight distribution at finish.

- Clubhead speed and smash factor (with launch monitor): look for consistent smash factor and controlled speed rather than maximal, erratic numbers.

- Balance hold: time you can hold your finish for 3-5 seconds without moving – a simple stability test.

Case study (applied biomechanics): an amateur golfer’s conversion

Profile: 45-year-old high-handicap golfer with inconsistent iron strikes and left-to-right misses (for a right-handed player).

- Initial assessment: early opening of the chest through impact, limited thoracic rotation, and poor weight transfer (balanced too much on trail side).

- Intervention: focused mobility for thoracic rotation, towel-under-armpits drill to keep arms connected, step-through drill for weight transfer, and single-leg balance exercises.

- Outcome after 10 sessions + home routine: more consistent strike pattern,reduced lateral misses,and an ability to hold a balanced finish. Dispersion reduced by ~25% and confidence increased.

Quick checklist to use before every practice session

- Warm up thoracic spine and hips for 6-8 minutes.

- Perform 8-10 medicine ball rotations or dynamic twists.

- Run 15-20 minutes of targeted drills (towel drill, step-through).

- End practice with 10 purposeful swings focused solely on the finish and balance.

SEO-friendly closing notes (internal use)

Use keyword variations naturally when publishing this article: “golf swing follow-through,” “follow-through drills,” “golf biomechanics,” “improve golf swing finish,” “golf swing balance,” and “clubface control.” Add internal links to related posts (e.g., “Thoracic Mobility for Golfers”, “Rotational Strength Workouts”, “Video Analysis Tools for Golf”) and external links to reputable sources (biomechanics research or PGA coaching resources) to strengthen topical authority. Include at least one high-quality image or video demonstrating the drills and add proper alt text such as “golfer performing step-through drill for follow-through balance”.