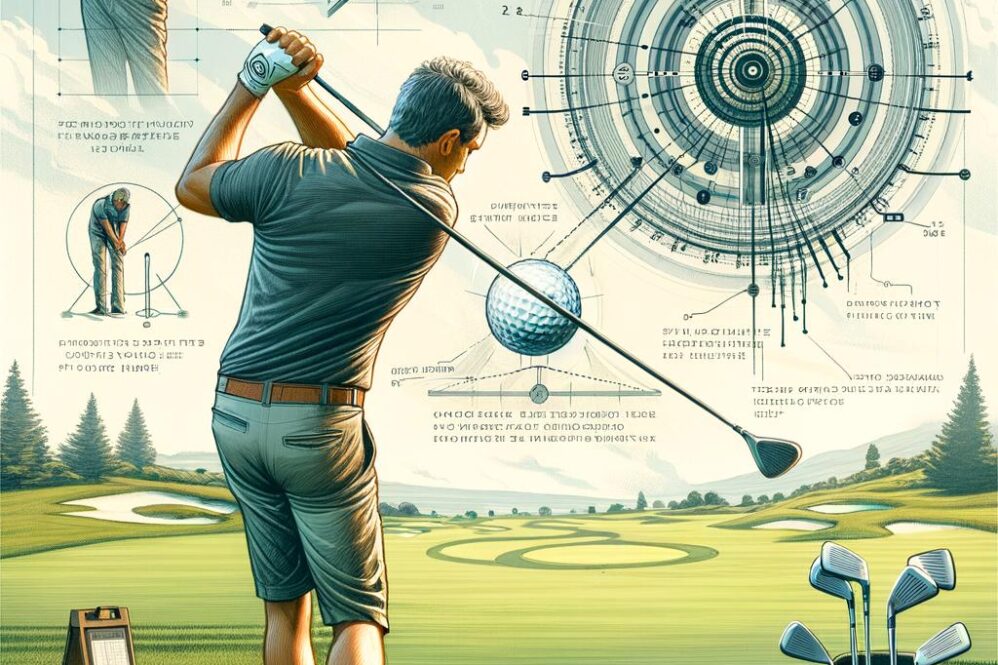

Arnold Palmer’s lasting impact on modern golf reaches well beyond his wins adn magnetic personality. At the heart of his influence is a swing that was both powerful and repeatable, an attacking but disciplined driver strategy, and a putting process that fused technical clarity with unshakeable confidence.Although his motion was long labelled ”unorthodox,” current research in biomechanics and performance data shows that his technique was remarkably efficient and can be broken down, taught, and adapted to today’s game.

This article reinterprets the main mechanical and tactical pillars of Palmer’s technique with targeted attention to three performance areas: full‑swing dynamics for superior ball‑striking, driver mechanics and decisions for greater accuracy and distance, and putting mechanics linked with green‑reading and routine design for better scoring. Using up‑to‑date biomechanical insights, motor‑learning science, and modern course‑management concepts, we translate Palmer’s movement patterns into clear building blocks and turn them into practical, research‑driven drills.

By weaving together historical footage, 3D swing analysis, and contemporary sport‑science findings, the sections below provide a structured model for golfers and coaches who want to absorb Palmer’s core principles-not mimic his individual quirks. The aim is to present a systematic path for fixing common driving errors, stabilizing impact conditions, and creating a resilient, repeatable putting stroke built on the same high‑performance foundations that powered Palmer’s career.

Kinematic Foundations of Arnold Palmer’s Swing Sequencing and Ground Reaction Forces

Arnold Palmer’s signature swing is a prime example of how efficient kinematics and ground reaction forces (GRF) can generate extraordinary power and control without disrupting tempo.At address, his slightly wider‑than‑shoulder stance and moderate knee flex (around 15-20°) established a strong platform to push force into the turf. Modern players should mirror this by prioritizing even, athletic weight distribution (55-60% on the lead foot with shorter irons, trending to 50-50 with the driver), a neutral spine tilt, and a firm but non‑tense grip. As the club moves away from the ball, Palmer followed a classic “ground-up” kinetic chain: the lower body starts, the torso winds, and the arms and club react. To train this pattern, rehearse a takeaway where the clubhead remains outside the hands for the frist 30-45 cm, the lead shoulder turns under the chin, and the hips turn roughly 30-40° while the shoulders rotate about 80-90°. This creates an efficient X‑factor stretch without a big lateral sway. On the course, that rotational stability supports consistent strike quality on sidehill lies, soft turf, or in heavy wind because the motion is rotary rather than slide‑dominant.

Palmer’s transition was defined by assertive,well‑timed use of GRF: pressure shifted into his lead side before the backswing was fully completed,followed by an energetic push into the ground that allowed his body to rotate and extend through impact. Golfers can copy this pattern by allowing the trail foot to bear up to 65-70% pressure at the top of the backswing, then deliberately moving pressure into the lead side early in the downswing while the upper body stays composed. To groove this,integrate simple range or indoor drills such as:

- Feet-together swings: Hit controlled half shots with the feet almost touching to encourage centered rotation and discourage lunging or sliding.

- Lead-heel plant drill: Raise the lead heel slightly in the backswing and “stamp” it down to launch the downswing, amplifying the sensation of initiating motion from the ground.

- Alignment-stick pressure check: Position an alignment stick just outside the lead hip; practice rotating around the lead leg instead of driving the hip into the stick, reinforcing rotary rather than lateral motion.

As mechanics improve,golfers can track gains with consistent low-point control (ball‑first contact with irons and divots starting 2-4 cm ahead of the ball) and tighter dispersion patterns on the range. Skilled players can further refine outcomes with launch‑monitor feedback-dialing in attack angle, club path (within ±2° of target), and spin rates-to chase added distance while preserving Palmer‑like shot‑shaping and accuracy.

Palmer’s efficient sequencing and GRF usage also influenced his short game and overall course management, where he combined a confident, assertive motion with clear tactical discipline. Around the greens, his pitching and chipping retained the same stable lower body and ordered rotation but on a compressed scale: narrower stance, weight biased to the lead side (60-70%), very little extra wrist hinge, and a smooth, body‑driven stroke.For any handicap, it is valuable to practice with objective, trackable targets, such as landing chips on a defined 1-2 yard landing zone or calibrating three stock wedge motions (such as, 9:00, 10:30, and full) to known carry distances.

- Clock-face wedge drill: Imagine the lead arm as the hand of a clock; rehearse backswing “times” while guarding tempo and GRF usage (firm lead side, steady feet).

- Penalty-avoidance strategy drill: On the course, choose conservative targets consistent with Palmer’s mantra of “aggressive swing to a smart target”-play to the biggest part of the green when danger hugs one edge, then fully commit to the chosen line.

- Wind and lie adaptation: In crosswind or sloping‑lie scenarios, nudge the ball a fraction back in the stance to lower flight slightly, maintaining the same ground‑driven rotation to stabilize the face through impact.

By deliberately connecting setup fundamentals, GRF‑driven sequencing, and controlled rotational motion to simple, repeatable strategic choices, golfers can sharpen ball‑striking, tighten short‑game proximity, and reduce errors through improved course management, on‑course decision‑making, and mental commitment to each shot-paralleling the competitive traits that defined Arnold Palmer’s career.

optimizing Driver Setup and alignment Parameters for Palmer-Style Power and Accuracy

Developing a long yet accurate driver game in the spirit of Arnold Palmer starts with a precise address position and club configuration that encourage an upward angle of attack while preserving face stability. For most players, this begins with the ball positioned off the lead heel, the driver shaft leaning slightly away from the target, and a setup that allows for roughly 2-4 degrees of positive launch angle potential. The stance should feel athletic and dynamic: feet just wider than shoulder width with about 55-60% of pressure on the trail foot at address to promote a complete, coiled turn. Staying true to Palmer’s bold style, the lead shoulder sits fractionally higher than the trail shoulder and the spine tilts subtly away from the target, yet without the excessive tilt that invites early extension. A practical checkpoint is feeling the sternum just behind the ball at address, combined with neutral grip pressure-secure enough for face control but relaxed enough for speed. Newer players can keep things simple by squaring the clubface to the target line and aligning the body parallel left (for right‑handers). More advanced golfers can refine by matching clubface aim to intended start line and body alignment to desired shot shape, such as a controlled Palmer‑style power fade.

To turn this address into Palmer‑like power and precision, golfers must coordinate alignment parameters with swing path and face orientation. Palmer often aimed slightly right of his target (as a right‑handed player) and then swung hard with a marginally leftward path to create his trademark power fade. Contemporary players can replicate this by choosing an intermediate aim point-like a leaf or old divot 1‑2 feet in front of the ball-then setting the clubface exactly at that reference while aligning feet, knees, hips, and shoulders just left of it. this establishes a useful “closed‑face‑to‑path” relationship for draws or “open‑face‑to‑path” for fades. On the practice tee, groove this with straightforward alignment exercises such as:

- Parallel Line Drill: Lay one club on the ground along the target line and another parallel to mark the foot line, ensuring the shoulders do not become overly open, a frequent cause of slices and lost distance.

- Gate Drill: Tee two balls or place alignment sticks slightly wider than the driver head 12-18 inches in front of the ball; work on starting drives through this “gate” to train a steady face and predictable start line.

- Launch Window Practice: Designate a 10-15 yard “window” between downrange markers and record how many drives finish inside it; first target 5 of 10 balls in the corridor, then progress toward 7 of 10 as control improves.

These routines help golfers of all skill levels match preferred shot shape with a repeatable address pattern, making it easier to reproduce under real‑world conditions such as narrow par‑4 fairways or crosswind tee shots.

Fine‑tuning equipment and sharpening situational awareness elevate this Palmer‑style driver model into a consistent scoring weapon. Proper driver loft, shaft flex, and lie angle should suit the player’s speed and attack angle: golfers swinging under 90 mph often see better launch and carry with 10.5°-12° of loft and a more flexible shaft, while speedier players above 100 mph may maximize distance using 9°-10.5° and a stiffer profile-assuming they can reliably strike the sweet spot. adjustable hosels and moveable weights can be tuned to complement your pattern-slight fade bias for those battling hooks, or draw bias for chronic slicers-while still respecting palmer’s belief in aiming boldly but swinging within control. On the course, adapt setup to environmental factors: into a strong headwind, move the ball a half ball back, reduce spine tilt, and emphasize a controlled, lower-spin flight; with a tailwind, maintain a more pronounced tilt and positive attack angle to take advantage of extra carry. To cement these habits, design practice sessions with measurable objectives, such as:

- Fairway Percentage Drill: Simulate 9 different tee shots, track how many land in a defined “fairway” zone, and target a 10-15% betterment in fairways hit over a month.

- Pressure Rehearsal: End range sessions by hitting three consecutive drives using your full pre‑shot routine, counting only those that would stay in a real fairway; this links visualization, commitment, and routine discipline to the technical setup and alignment you’ve built.

By deliberately aligning technical checkpoints, equipment choices, and on‑course adjustments, golfers can develop a driver game that echoes Palmer’s signature combination of aggression and accuracy, leading to better positioning, heightened confidence, and more realistic birdie chances from the short grass.

Translating Palmer’s Dynamic Tempo into Repeatable Full-Swing Mechanics

Arnold Palmer’s tempo blended athletic assertiveness with orderly sequencing rather than raw speed,and that balance can be adapted into a modern,repeatable full swing. Start by building a consistent rhythm ratio between backswing and downswing, commonly approximated as 3:1 in duration: a smooth, unhurried backswing followed by a decisive but not frantic change of direction. At address, maintain an athletic yet neutral posture with spine tilt of approximately 30-35° from vertical, knee flex of 15-20°, and weight biased 55-60% on the trail foot with the driver to enable a complete turn. To echo Palmer’s dynamic but reliable action, allow the club, arms, and torso to move together at the start, keeping the clubhead low to the ground for the first 30-40 cm to encourage width. As the lead arm reaches parallel to the ground, the shaft should sit close to parallel to the target line, reducing across‑the‑line positions that often disturb both tempo and face control. This setup and motion framework helps beginners who may need slower rehearsals and also supports better players who can fine‑tune tempo using ball‑flight and launch data.

To convert that rhythm into trustworthy impact conditions,prioritize sequencing during transition and downswing. Palmer’s aggressive appearance masked a technically sound, lower‑body‑driven action: from the top, pressure shifts first toward the lead foot (building to 70-80% lead‑side pressure by impact) before the torso and arms release. This prevents “hitting from the top,” preserves lag naturally, and keeps the club on plane. With irons, a slightly descending attack angle (roughly −3° to −5°) and forward shaft lean of 5-10° at impact supports ball‑first contact and predictable spin. On firm or windy days-conditions Palmer handled superbly-maintain the same tempo but shorten the backswing to chest‑high, letting rhythm regulate distance and trajectory. Effective training drills include:

- Metronome Swings: Use a metronome or tempo app (around 72-84 BPM).Take the club back over three beats and swing through on the fourth,cultivating Palmer‑like assertiveness without rushing.

- Step-Through Drill: Hit half shots where you step the trail foot toward the target after impact, developing natural pressure shift and continuous motion.

- Impact Line Drill: Draw a chalk line on a mat or use a divot board. With mid‑irons, ensure the bottom of the arc (divot or board contact) consistently lands 2-4 cm ahead of the ball, confirming compressive, tempo‑driven contact.

These exercises foster a fluid, repeatable tempo that holds up under stress-whether you are learning to achieve solid contact or an advanced golfer chasing tighter dispersion by distance and spin consistency.

to connect this tempo‑first full swing with on-course decision-making in Palmer’s attacking yet calculated style, use rhythm as the constant and adjust club and target selection around it. A dependable tempo allows you to pick bolder lines only when your current ball flight and dispersion justify the risk. Off the tee, choose a driver or fairway wood with loft and shaft profile suited to your speed and natural launch (e.g., a 10.5° driver with mid‑launch shaft for moderate speeds), then maintain one consistent tempo regardless of club choice. On approach shots into tight pins or in shifting winds, stick to the same rhythm but choose more club and play a controlled three‑quarter motion, trusting tempo to manage distance. Reinforce this with situational practice such as:

- 9-ball Flight Tempo Practice: Hit draws, fades, and straight shots, but keep the same rhythm each time, changing only setup and face/path relationships.This parallels Palmer’s capacity to shape shots without altering pace.

- “Par-18” Wedge and Short-Iron Game: Build a nine‑hole “course” on the range with targets from 60-140 yards, scoring each swing as a real hole. Track how often you maintain your chosen tempo when there is a score attached.

- Pre-Shot Routine Checkpoints: Before every full swing, include a brief waggle and one slow‑motion rehearsal to feel backswing length and transition; then step in and replicate that cadence on the actual shot.

By uniting Palmer‑inspired dynamic tempo with sound mechanics, appropriate equipment, and disciplined strategy, golfers can convert improved full‑swing rhythm into lower scores, tighter patterns, and clearer decisions in genuine playing conditions.

Evidence-Based Corrections for Common Driving Faults Using Palmer-inspired Drills

Most driving problems begin before the club moves, so a data‑driven fix starts with the address structure Palmer valued: an athletic, functional setup that nurtures an in-to-out path and centered strike. For many players, a neutral to slightly closed stance with the driver-lead foot flared about 25-30°, trail foot square, ball positioned just inside the lead heel-encourages optimal launch while minimizing slice tendencies. The spine should tilt 5-10° away from the target, placing the sternum a touch behind the ball to support an upward hit. To implement this, build a simple Palmer‑style alignment station on the range: set one club along your toe line and another along the ball line, both parallel to the target, then rehearse your grip with light-to-moderate pressure (about 4-5 on a 10 scale), ensuring the trail hand is not overly weak. This clear visual station gives beginners an accurate reference for alignment, while accomplished golfers can micro‑adjust stance width and ball position for maximum clubhead speed and stability under tournament pressure.

After the setup is reliable, the most common driving flaws-over-the-top motion, early extension, and erratic low point-can be reduced with Palmer‑inspired movement drills that reinforce a more effective kinematic pattern.palmer attacked the ball with conviction but from a fundamentally sound geometry: a complete shoulder turn, relatively quiet lower body at the top, then forceful lead‑side rotation through impact.To engrain this shape, use the following range drills:

- Trail-Foot-Back Drill: Pull the trail foot 15-20 cm behind the lead foot while keeping normal ball position. This slightly closed stance encourages an inside path and helps slicers feel the club moving more around the body instead of cutting across it.

- Pause-at-the-Top Drill: Make three‑quarter swings with a deliberate 1-2 second pause at the top, sensing the downswing starting from the lead hip and torso rather than the hands. Measure contact quality with impact tape or marked balls, aiming to cut off‑center strikes to fewer than 3 per 10 balls.

- Tee-Height and Launch Drill: Use a higher tee (about half the ball above the crown) and place an empty ball box 10-15 cm in front of the ball on the target line. The objective is to avoid the box while launching the ball high, reinforcing an upward attack angle and centered strike.

These drills embody core biomechanical ideas-ground‑up sequencing, preserved spine angle, and delayed wrist release-yet remain accessible: beginners focus on brushing the tee and starting the ball inside their alignment line, while elite players monitor start line, curvature, and launch window to refine a dependable stock shot.

For driving improvements to lower scores, the technical work must pair with smart course management, mirroring Palmer’s assertive yet calculated tee strategy. Instead of always swinging at maximum effort, every golfer should define a “scoring swing”: a controlled driver or 3‑wood action at roughly 80-85% perceived effort that keeps the ball in play when it matters most. On a tight par 4 or in a heavy crosswind, for instance, select a target that gives a pleasant wedge distance (perhaps 90-110 yards) rather than gambling on cutting a risky corner. Practise this mindset in on‑course or simulated sessions with “fairway‑only” games:

- Fairway or Bunker Drill: on the range, mark an imaginary fairway about 20-25 yards wide. Hit 10 drives with your scoring swing,counting only those finishing inside as prosperous.Aim for at least 7/10 fairway hits before layering on extra speed.

- wind and Lie Adjustments: Into the wind, tee the ball a little lower (about one‑third above the crown) and favour a lower‑spinning shot; with the wind, keep the tee higher to promote high launch and carry. From uneven lies on the course, narrow the stance by 2-3 cm to emphasize balance and accept a smaller carry number if necessary.

By merging Palmer‑inspired mechanical corrections with restricted, purposeful practice and thoughtful club selection, golfers can translate better swing patterns into measurable results: higher fairway percentages, fewer penalty shots, and more second shots from attackable positions-ultimately reducing both driving‑related stress and total scoring average.

Biomechanical principles of Palmer’s Putting Stroke and face Control

Palmer’s putting motion showcases a blend of straightforward geometry and efficient body mechanics that adapts well to modern green speeds and equipment.At address, the shoulders and hands create a stable triangle; the shoulders act as the primary engine while hands and wrists stay comparatively quiet to stabilize the face. For most golfers, a slight forward shaft lean of 2-4 degrees with the ball positioned just slightly forward of center promotes a crisp strike with modest effective loft at impact (around 2-3 degrees effective loft).Stance width can be shoulder‑width or a bit narrower, but the essentials are a balanced base, light grip pressure (around “3-4 out of 10”), and eyes placed either directly above the ball or just inside the line to improve aim. Palmer leaned toward a firm, authoritative stroke: the putter head travels on a gentle arc, with the face staying square to that arc rather than square to the target line throughout. This arcing path is biomechanically natural because it reflects the rotation of spine and shoulders; artificially forcing a “straight‑back, straight‑through” stroke often adds unwanted hand manipulation.

Face control in Palmer’s stroke stems from sequencing, not hand steering. The shoulders initiate the stroke, with the lead shoulder moving slightly down and back on the way back, then up and toward the target on the through‑stroke while the lower body stays stable. To encourage a consistent face angle, many golfers benefit from a slight forward press before starting, which presets the hands and engages larger muscles rather of the fingers. On fast greens or in gusty conditions,Palmer‑style firmness in the stroke reduces deceleration and keeps the face more stable through impact.To build this motion, use the following checkpoints and drills:

- Setup checkpoints: Feet parallel to the target line; forearms matched to putter shaft angle; grip running through the lifelines of both hands to lessen wrist hinge.

- Gate drill for face control: Place two tees just wider than the putter head and make 20-30 strokes so that the head passes cleanly through; aim to start 10 putts in a row along a 3‑foot chalk line.

- One-handed lead-arm drill: Roll 10-15 short putts (3-5 feet) using only the lead hand to feel shoulder‑driven motion and avoid flipping; then repeat with both hands while preserving that sensation.

As these mechanics become automatic, golfers can change speed and line with more confidence, trusting that the clubface will return predictably to square-even on key putts in tournaments or competitive matches.

Applying Palmer’s biomechanical approach to real‑course strategy means relying on a consistent stroke so the mind can focus on green reading and speed management. Instead of trying to guide the putter, players can invest attention in slope, grain, and environmental factors such as morning dew or afternoon drying. A practical routine blends technical and mental elements:

- Pre-putt read: Inspect the putt from both low and high sides, imagine the ball entering on the high side of the cup, and choose a pace that would finish 12-18 inches past the hole on level putts.

- Stroke rehearsal: Make 1-2 practice swings beside the ball, focusing on shoulder‑led motion and a square face at impact; match the stroke length to the desired rollout distance, not merely to the hole location.

- Performance drill: Build a “Palmer circle” of eight tees at 3 feet surrounding the cup. Putt from each tee until you’ve holed 16 consecutive putts, sustaining identical setup and face control; low‑handicap players can expand the circle to 4-5 feet while aiming for the same standard.

Over time, this blend of sound mechanics, structured practice, and thoughtful green‑reading habits will tighten key statistics-such as three-putt avoidance and one-putt conversion inside 6 feet-and support the confident, assertive scoring mindset that Palmer displayed on demanding championship greens.

Green-Reading, Start-Line Management and Pace Control in the Spirit of Palmer

In keeping with Palmer’s assertive yet analytical style, effective green reading begins long before you address the ball. As you approach the putting surface, scan from 20-30 yards out to understand overall tilt, tiers, and potential runoff areas, then refine that picture from behind the ball and behind the hole. Concentrate on three key elements: slope direction (often toward bunkers, drains, or water), severity of break (gentle, moderate, or steep), and grain (especially on Bermuda, where growth tends to follow drainage patterns or angle toward the setting sun). Adopting a straightforward rating system-such as giving each putt a 1-5 break score-helps golfers make more consistent decisions. Newer players should focus on identifying the dominant slope and playing for one clear break, whereas advanced golfers can refine their perception using methods like feeling slope with their feet and visualizing the ball tracing its final 30-40% of the putt. In line with Palmer’s approach, the objective is decisive commitment: once the read is chosen, trust it fully.

turning that read into accurate start-line management demands precise setup and a disciplined stroke. Begin with a consistent routine: mark a line on the ball or align the logo to the intended start line, then set the putter face perpendicular (90°) to that mark before stepping into your stance. Ensure your eyes are either directly over the ball or 0-2 inches inside, your shoulders are parallel to the target line, and grip pressure is light but stable.To emulate Palmer’s “hit-your-line” ideology, prioritise a stroke that delivers the face within 1° of square at impact. Train this with gate‑style drills:

- Putter gate Drill: Position two tees just wider than the putter head and make strokes without clipping the tees, encouraging a centered, square strike.

- Ball Gate Drill: Set two tees 1-2 ball widths in front of the ball along your start line and roll putts through the gate; if the ball misses, the face was misaligned.

- Mirror or Chalk-Line Work: Use a putting mirror or chalk line on flat 5-8 foot putts to verify alignment and start‑line consistency.

Frequent problems-like pulls from closed shoulders or pushes from an overactive trail hand-can be corrected by rehearsing neutral shoulder alignment and keeping the lower body stable. With repetition, both beginners and low handicappers can learn to trust their reads and roll putts confidently on their intended start lines, mirroring Palmer’s poise under pressure.

Pace control converts accurate reads and reliable start lines into made putts,especially when aligned with Palmer’s aggressive‑but‑sensible philosophy. Rather than letting the ball die at the cup, adopt a baseline speed that would roll the ball 12-18 inches past the hole on level putts, adjusting a touch softer uphill and slightly firmer downhill. Build this feel with targeted drills:

- ladder Drill: Place tees at 3, 6, 9, and 12 feet; hit three balls to each distance, trying to finish within a 12‑inch zone past the tee.

- One-Handed Trail-Hand Drill: Roll 10-15 putts from 20-30 feet using only the trail hand to enhance feel, rhythm, and speed awareness.

- Uphill/Downhill Calibration: On the practice green, putt from a central spot to one uphill and one downhill hole, noting how much stroke length changes to produce equal rollout.

Course conditions-slow vs. fast greens,into‑ or down‑wind putts-should influence subtle speed changes,but the broader goal holds: for better players,keep three‑putts to one per round or fewer; for newer golfers,target fewer than three per round. By combining improved reading skills,disciplined start‑line habits,and robust pace control with Palmer’s fearless yet thoughtful mindset,golfers can reliably shave strokes on the greens,turning more chances into birdies and more long putts into simple two‑putt pars.

Integrating Palmer-Inspired Practice Structures for Sustainable Performance Gains

Building on Arnold Palmer’s tradition of disciplined yet inventive practice, a palmer‑inspired training structure starts with consistent pre-shot fundamentals and dependable swing mechanics. Organize full‑swing sessions into short, focused blocks that alternate between technical work and target-based performance instead of hitting balls without a plan. Begin with 10-15 minutes of wedges and short irons at 50-70% effort, emphasizing balanced posture (hip hinge around 25-30°, light knee flex), a neutral grip (lead‑hand “V” aimed between chin and trail shoulder), and square clubface alignment (leading edge matching the target line). Once these basics are checked, move into deliberate drills such as:

- gate Drill: Place two tees just outside the toe and heel of the clubhead, 2-3 cm away, to train center‑face contact and minimize excessive face rotation.

- 9-Shot Matrix: Channeling Palmer’s shot‑making ability, practise three trajectories (low, mid, high) with three shapes (draw, straight, fade). Modify ball position (1-2 balls forward for higher shots, slightly back for lower) and adjust face-to-path relationship (face 1-2° closed to path for a draw, 1-2° open for a fade).

- Alignment ladder: Lay 2-3 alignment sticks to illustrate foot line, ball‑target line, and swing path, rehearsing an inside‑to‑neutral path (roughly 2-4° in‑to‑out for a draw) and consistent shoulder alignment.

By rotating between focused mechanical feedback (video, mirrors, launch monitors) and task‑based challenges, golfers can grow a swing that is fundamentally solid yet adaptable under real‑course pressure.

Palmer’s success also reflected unwavering attention to short game precision and on-course problem solving, both of which should be embedded into contemporary practice. Rather than mindlessly chipping to one flag,structure short‑game “circuits” that recreate different lies,slopes,and speeds.As a notable example, set up a 10‑ball up‑and‑down challenge from varied situations: tight fairway lies, light rough, buried bunker shots, and downhill chips around the green. Tailor techniques to each scenario: from tight lies, use a slightly forward shaft lean, ball centered or slightly back, and a low‑flight “check and release” chip with a 52-56° wedge; from rough, add loft and speed, open the face 5-10° to maintain bounce, and stand a bit taller to avoid digging. Establish specific performance goals such as getting at least 7 of 10 chips inside a 1.8 m (6 ft) circle or achieving 2-putts on 90% of 10 m lag putts. To build mental toughness, follow Palmer’s example by treating every practice shot as if it were on the course: pick a landing spot, visualize the spin and rollout, and execute with full routine. Over weeks, this approach helps golfers not just hit more shots, but consistently choose the highest‑percentage option based on lie, firmness, and wind-directly improving scoring under pressure.

Long‑term performance gains also depend on deliberate course management training that fuses Palmer’s attacking instincts with thoughtful risk control.During practice rounds, assign each hole a strategic objective rather than focusing solely on score. On par 4s,such as,practice selecting a club that leaves your preferred approach distance (say 110-130 yards) rather of automatically hitting driver. Track fairways hit,strokes gained by club choice,and average proximity to the hole from key yardages. Apply Palmer‑style decision rules such as:

- Play away from “double-bogey zones” (water, out‑of‑bounds, heavy penalty areas) by aiming to the fattest section of fairway or green, even at the cost of a longer putt or approach.

- Wind and elevation adjustments: Add or subtract about one club for every 15-20 km/h (10-12 mph) of headwind or tailwind, and one club for each 9-12 m (10-13 yards) of elevation change, then validate those adjustments on the course.

- Conservative-aggressive principle: Pick a conservative target (the larger portion of the green or safer side of the fairway) but make an aggressive, fully committed swing.

At the end of each round,review simple metrics-greens in regulation,up‑and‑down percentage,penalty shots,and three‑putts-then base the following week’s practice on your biggest leaks. This feedback loop, anchored in Palmer’s training ethic, enables beginners to prioritize solid contact and safe targets while allowing low handicappers to refine shot‑shaping, spin, and trajectory-all within a repeatable, data‑informed framework that steadily enhances scoring.

Q&A

**Q1. What are the defining biomechanical characteristics of Arnold palmer’s golf swing?**

Arnold Palmer’s swing is defined by:

– **Dynamic lower-body action:** Forceful hip rotation and weight shift from trail to lead side, generating meaningful ground reaction forces.

– **large upper-body turn:** A complete shoulder rotation, often beyond 90°, creating a pronounced X‑factor (hip-shoulder separation).

– **Relatively upright swing plane:** Especially with longer clubs,encouraging a high,penetrating trajectory.

– **Distinctive follow-through:** A vigorous, occasionally “helicopter‑style” finish that reflects rapid rotation rather than a posed aesthetic.

From a biomechanical view, Palmer turns linear weight shift into rotational speed very efficiently, preserving enough dynamic balance to repeat impact positions despite an unconventional finish.—

**Q2. How can recreational golfers adapt Palmer’s swing principles without copying his idiosyncratic style?**

Recreational players should pursue the **core principles** rather than the outward look:

– Build a **sound setup** (athletic posture, neutral grip, stable stance width).

– Emphasize **ordered rotation**: pelvis leads, then torso, then arms and club.

– Use **controlled aggression**: accelerate through impact while maintaining posture and balance.

– Preserve a **functional rhythm** rather than imitating Palmer’s exact tempo or follow‑through.

The objective is to integrate his efficient sequencing and commitment to the shot, not to perfectly copy his unique motion pattern.—

**Q3. Which aspects of Palmer’s driving fundamentals are most relevant to improving modern tee shots?**

Transferable fundamentals include:

– **Strong but not extreme grip:** Promotes a square face at impact with a slight draw bias for both distance and stability.– **Ball position and stance:** Ball just inside the lead heel and a moderately wide stance to support higher clubhead speed.– **Spine tilt away from the target:** At address, a small rightward tilt (for right‑handers) fosters an upward attack angle and improved launch.

– **Commitment through impact:** Acceleration through the strike, minimizing steering or deceleration.

Together, these elements help players optimize launch-higher launch, efficient spin-and tighten dispersion off the tee.—

**Q4. How does Palmer’s use of ground reaction forces contribute to driving distance and consistency?**

Palmer produced power from the ground up by:

– **Loading the trail side** during the backswing, increasing vertical and horizontal forces under the trail foot.

- **Shifting pressure aggressively to the lead side** early in the downswing, generating rotational torque about the vertical axis.

– **Extending through impact** via a braced lead leg, which converts vertical force into clubhead speed.

For modern golfers, the lesson is to train tangible pressure shifts under the feet and a firm lead‑side post through impact.This supports both extra distance and repeatable low‑point control.—

**Q5.What role does swing plane and clubface control play in Palmer-style driving accuracy?**

Palmer’s relatively upright plane allowed:

– A more **vertical delivery** with the driver, aiding high‑launch, mid‑spin flight.

– Easier **face orientation control**, as a steeper arm plane can definitely help some players naturally match face position to path.

The crucial factor is the **face-path relationship**:

– A slightly inside‑to‑square path with a nearly square face promotes a stable draw.

– Too much divergence between face and path yields excessive curvature (hooks or slices).

Adopting Palmer’s approach calls for drills that stabilize plane (alignment rods, mirrors) and improve face awareness (grip, lead wrist conditions, impact feedback).—

**Q6. How did Arnold Palmer’s putting technique support distance control and consistency?**

Palmer’s putting, though idiosyncratic visually, adhered to solid fundamentals:

– **Quiet lower body:** Minimal hip and leg motion for a dependable platform.- **Shoulder-driven stroke:** A rocking shoulder motion provides the primary engine rather of active wrists.

– **Consistent tempo:** Similar rhythm on short and long putts, with distance governed mostly by stroke length.

– **Firm,positive contact:** Limits variability in ball speed,especially useful on slower or inconsistent greens.

Collectively, these traits improve distance control by making ball speed more predictable and reducing reliance on delicate wrist timing.—

**Q7. What are the main mechanical checkpoints to “perfect putting” in the spirit of Palmer’s approach?**

significant checkpoints include:

1. **Setup alignment:** Eyes roughly over or just inside the ball line; shoulders parallel to the target line; putter face square.2. **Grip neutrality:** Light‑to‑moderate pressure, low forearm tension, and minimal hand action.

3. **Stroke arc control:** A natural slight arc (inside-square-inside) that respects body anatomy rather than a forced straight‑back, straight‑through path.

4. **Low‑point stability:** Quiet head and chest so the bottom of the stroke consistently occurs at or just ahead of the ball.

5. **face stability:** Limited face rotation relative to the arc; many errors stem from face misalignment at impact more than path issues.By maintaining these reference points, golfers can approach the resilient putting performance Palmer displayed in high‑pressure moments.—

**Q8. How can biomechanics inform practice protocols for improving driving consistency using Palmer’s model?**

Biomechanics points toward practice that emphasizes:

– **Segmental sequencing drills:** Slow‑motion swings where hips lead, then torso, then arms, validating proper kinematic order.

– **Pressure-shift training:** Pressure mats or simple “step drills” to feel trail‑to‑lead loading across transition.– **Low-point and strike control:** tee‑height variations and impact tape to calibrate center‑face contact and attack angle.

– **Speed windows:** Alternating 70%, 85%, and 100% effort swings to keep mechanics stable at different intensities.

These methods mirror Palmer’s powerful yet stable driving, prioritizing efficient force transfer and consistent face‑to‑path conditions over superficial style.—

**Q9. What practice structures are recommended to integrate Palmer-inspired putting mechanics into everyday training?**

Evidence‑based putting structures include:

– **Blocked then random practice:** Begin with repeated putts from one distance (e.g., 10 from 6 feet), then switch to random distances and breaks to sharpen adaptability.

- **Outcome plus process focus:** Blend mechanical cues (such as “steady head, shoulder rock”) with performance targets (for instance, “roll the ball 30 cm past the hole”).

– **Feedback loops:** Use gates for start‑line accuracy, chalk lines or strings for path, and auditory/visual tools for tempo awareness.

– **Pressure simulations:** Create scoring games (like “up‑and‑down in three attempts or fewer from varied spots”) to recreate Palmer’s competitive decisiveness.

This framework helps transfer refined mechanics from practice greens to actual play under realistic mental demands.—

**Q10. How can integrating Palmer’s driving and putting concepts improve overall scoring performance?**

Scoring is heavily shaped by:

– **Tee‑shot reliability:** Fewer penalties and recovery shots through improved dispersion and sufficient distance.

– **Proximity to the hole:** better driving usually produces shorter approaches and more birdie looks.

– **Three‑putt avoidance:** Strong lag putting and short‑putt conversion reduce wasted strokes.

By merging Palmer’s efficient driving mechanics (forceful yet controlled) with robust putting fundamentals (stable stroke, tight speed control), golfers can address both ends of the scoring spectrum-limiting big numbers from the tee and saving strokes on the greens. Across a season,this dual improvement can meaningfully lower handicaps and reduce score volatility.—

**Q11. What common misconceptions arise when players attempt to “swing like Arnold Palmer,” and how should they be addressed?**

frequent misconceptions include:

– **Copying the finish instead of the sequence:** The dramatic follow‑through is a consequence of powerful rotation, not a template to mimic. Focus on impact and sequencing,not post‑impact poses.

– **Overvaluing effort:** Palmer appeared aggressive, but his motion was highly coordinated. Excess tension or simply “swinging harder” without structure hampers consistency.

– **Ignoring individual anatomy:** Palmer’s posture and limb proportions were unique. Golfers should respect their own mobility, limb lengths, and physical limits.

Instruction should reframe “swing like palmer” as “apply palmer’s core concepts”-effective ground use, proper sequencing, decisive execution-within each golfer’s personal biomechanical boundaries.—

**Q12. How can golfers evaluate whether Palmer-inspired changes are actually improving performance?**

Assessment should be both **quantitative** and **qualitative**:

– **Driving metrics:** Fairways hit, average and dispersion of driving distance, penalties per round, and strike quality via launch‑monitor or impact feedback.

– **Putting metrics:** Three‑putt rate, make percentage from key bands (3-6 ft and 6-12 ft), and average leave distance on long putts.

– **Performance under pressure:** Self‑reported confidence,ability to repeat mechanics late in rounds,and results in competitions or pressure drills.

Sustained gains in these metrics-rather than brief range success-show that Palmer‑inspired mechanics and practice structures are genuinely improving scoring.

Arnold Palmer’s technique offers a detailed, adaptable model for golfers seeking better driving performance and sharper putting through sound biomechanics and purposeful practice design. His dynamic yet fundamentally efficient full‑swing shows how coordinated lower‑body initiation, stable posture, and sequenced rotation can yield both distance and accuracy from the tee. At the same time, his putting framework emphasizes the value of a repeatable stroke, refined speed control, and strong perceptual skills in reading greens.

By blending Palmer’s principles with current evidence on kinematics, motor learning, and strategic course play, golfers can move beyond simple imitation toward informed adaptation. The objective is not to duplicate Palmer’s personal style, but to absorb the mechanical and strategic foundations that made his game so effective, then apply them step by step through targeted drills, measurable feedback, and realistic practice. Ultimately, mastering a “Palmer‑inspired” model involves ongoing analysis, experimentation, and refinement. Players who pursue improvement with the same mix of intensity, creativity, and discipline that defined Palmer’s career are best positioned to increase driving power and accuracy, upgrade putting consistency, and convert those technical advances into lower scores when it counts most.

Unlock Arnold Palmer’s Genius: Drive Longer, Putt Truer, Score Lower

The Palmer Blueprint: Power, Grit, and Smart Golf

Arnold Palmer didn’t own the prettiest swing on Tour, but he drove the ball with fearless power, holed clutch putts, and attacked golf courses with bold, smart strategy. You can’t copy his personality, but you can copy the practical pieces of his game that lead to longer drives, truer putting, and lower golf scores.

Below you’ll find an evidence-based, Palmer-inspired guide that blends classic fundamentals with modern golf performance concepts: biomechanics, course management, and intentional practice. Use it to tune up your driver swing, sharpen your putting stroke, and build a scoring mindset that travels to any course.

Drive Longer the Palmer Way

1. Build a Powerful golf Setup

Palmer’s golf stance looked athletic and aggressive. A strong setup makes it easier to generate clubhead speed without extra effort.

- Ball position: Just inside the lead heel with the driver.

- Stance width: Slightly wider than shoulder-width for stability.

- Spine tilt: Small tilt away from the target, with lead shoulder slightly higher.

- Grip pressure: Firm enough to control the club, but not tense in the forearms.

This athletic address position aligns with modern biomechanical principles: a wider base and slight tilt help you rotate around a stable center, maximizing energy transfer through impact.

2. Make an “All-In” Backswing

Palmer generated more distance by making a full, committed shoulder turn.Even if your flexibility isn’t perfect, you can create a powerful coil.

- Rotate the shoulders 90° relative to the target line (or as close as is pleasant).

- Allow the lead heel to lift slightly if it helps you complete your turn.

- Keep the trail knee flexed to avoid swaying off the ball.

Think of it as storing elastic energy. The bigger the controlled turn, the greater the potential clubhead speed on the way down.

3. Unleash Through the Golf Ball, Not At It

Palmer swung “through” the ball with aggressive acceleration. Many amateurs decelerate or try to “steer” the driver.Instead, focus on swinging fast through a point a few inches past impact.

- feel the clubhead trailing slightly in the downswing, then whipping through at the bottom.

- Keep your chest rotating to the target-no stopping at impact.

- Finish with your belt buckle facing the target and weight mostly on the lead side.

4.Biomechanics for Longer Golf Drives

| Power Key | What It Does | Simple Check |

|---|---|---|

| ground Force | Uses legs to push and rotate | Can you feel pressure into lead foot before impact? |

| Hip Separation | Hips lead, torso follows | At halfway down, are hips open while chest is still closed? |

| Lag Angle | Maintains wrist hinge | Lead arm & shaft form a sharp angle mid‑downswing |

5. Palmer-Inspired Driving Drills

a) “Hit it Hard, Hold Your Finish” drill

This driving range drill blends Palmer’s aggression with modern balance control.

- Set up with your normal golf driver and tee height.

- Swing with 80-90% effort, focusing on accelerating through impact.

- Freeze your finish for 3 seconds.If you’re falling over, you’re swinging out of control.

Goal: Swing hard, but stay balanced. More controlled speed equals longer, straighter drives.

b) “Step-Through” Power Drill

- Address the ball normally.

- Start the downswing, then step your trail foot toward the target as you swing through.

- Let your body naturally rotate and move forward.

This exaggerates weight shift and helps you feel the ground forces that create real distance without extra strain.

Putt Truer With Palmer’s Fearless Stroke

1. Own a Simple,Repeatable Putting Setup

Palmer’s putting stroke was compact and confident. You don’t need an exotic putting style to roll the golf ball online.

- Eyes: over or just inside the target line.

- Grip: Light but secure; use either a traditional or claw grip-whichever keeps wrists quiet.

- Ball position: Slightly forward of center for an upward strike and true roll.

- Posture: Stable, slight bend at hips, arms hanging naturally.

2. Rock the Shoulders, Not the Wrists

Consistent putting relies on a pendulum motion. Let your shoulders rock while the hands and wrists stay quiet.

- Imagine your putter grip connected to your chest.

- The backswing and through-swing should be about the same length on short putts.

- Maintain steady head position-listen for the ball to drop before you look.

3. Master Distance Control: Lag Putting Fundamentals

Palmer was fearless, but he also left himself tap-ins. Good lag putting reduces three-putts and lowers your handicap fast.

| Distance | Backstroke Feel | Target Miss Range |

|---|---|---|

| 10 feet | Short,smooth | ±1 ft past hole |

| 20 feet | Medium length | ±2 ft past hole |

| 40 feet | Long,relaxed | ±3 ft past hole |

4. Simple Putting Drills for Truer Rolls

a) Gate Drill for Start Line

- Place two tees just wider than your putter head, forming a “gate.”

- Hit 10 putts from 5-6 feet, trying not to hit either tee.

- Focus on a square face at impact.

Do this before every golf round to lock in your start line.

b) “Around the Clock” Pressure Drill

- Set 6-8 golf balls in a circle, 3 feet from the hole.

- Putt each ball in sequence; if you miss, start over.

- Work up to completing three perfect circles.

This builds clutch putting confidence similar to what Palmer displayed under Sunday pressure.

Score Lower With Palmer-Style Course Management

1. Play Bold, Not Reckless

palmer attacked, but he also knew when to take his medicine. Smart golf shot selection can save more strokes than a new driver.

- know your “stock” yardages with every club in the golf bag.

- choose the widest part of the fairway, even if it means less distance.

- On approach shots, aim for the safe side of the green when trouble is near the pin.

2. Pre-Shot Routine: Your on-Course Superpower

palmer looked decisive over every golf shot. A consistent pre-shot routine keeps your mind quiet and improves contact.

- See it: Pick a clear target and shot shape.

- Feel it: Make one or two rehearsal swings with that motion.

- Commit: Step in, align, and pull the trigger within 10 seconds.

This routine works for drives, irons, wedge shots, and putts-creating a rhythm you can trust under pressure.

3. Manage the “Big Miss” Off the Tee

To lower scores quickly, eliminate penalty strokes and lost golf balls.

- If your big miss is a slice,aim slightly left and pick a driver setup that encourages a neutral path.

- On tight holes, consider 3-wood or hybrid instead of driver.

- Practice a fairway-finder swing at 70-80% speed that you can rely on when the hole looks intimidating.

arnold Palmer’s Mental Game: Confidence You Can Copy

1.Embrace the “go For It” Mindset-Wisely

palmer’s charisma came from his willingness to take on tough golf shots. Use this energy, but tether it to smart risk-reward decisions.

- Visualize success before every swing-see the ball flying and landing where you want.

- Set round goals that you can control: process, routines, and commitment, not just score.

- Accept that some aggressive plays will fail; learn, adjust, and move on.

2. Short Memory after Bad Shots

Palmer hit his share of wild drives, but he never stayed angry for long. The ability to reset quickly is a defining trait of elite golfers.

- After a bad shot,acknowledge it quickly: “That was a pull hook.”

- Take one learning point: alignment, tempo, or decision error.

- Use a reset cue as you walk-deep breath, club twirl, or touching your glove-then focus on the next golf shot only.

Practical Training Plan: Bring Palmer’s Genius into Your Practice

| Day | focus | Key Drill |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Driver Setup & Balance | Hit It Hard, Hold Your Finish |

| Day 2 | Putting Start Line | Gate Drill, 50 putts |

| Day 3 | Lag Putting | 10-20-40 ft distance ladder |

| Day 4 | Driving Accuracy | Fairway-finder swing to targets |

| Day 5 | On-Course Strategy | Play 9 holes: no penalty strokes |

Repeat this weekly, tracking fairways hit, greens in regulation, and number of putts per round. Thes golf statistics give you clear feedback on where your game is improving and where to focus next.

Benefits You’ll Notice Within a Few Rounds

- Longer, more controlled drives: From better rotation, ground force, and an aggressive yet balanced finish.

- Fewer three-putts: Thanks to a solid putting stroke, improved distance control, and pressure-tested short putts.

- Smarter decisions under pressure: Using Palmer-style course management to avoid big numbers.

- Higher golf confidence: A repeatable pre-shot routine and clear practice plan you can trust.

First-Hand style “Case Study”: A Weekend Golfer Transformation

Imagine a 15-handicap golfer who hits the occasional 260-yard drive but struggles with wild misses and three-putts. By adopting these palmer-inspired strategies, their season might look like this:

| Area | before | After 8 Weeks |

|---|---|---|

| Average Fairways Hit | 5 / 14 | 9 / 14 |

| Average Putts | 36 per round | 31 per round |

| Penalty Strokes | 4-5 per round | 1-2 per round |

| handicap Index | 15.0 | 11.5 |

The mechanics haven’t become “perfect.” Instead, the golfer has learned to swing aggressively with control, putt with confidence, and think like a strategist-exactly the type of genius that made Arnold Palmer a legend.

Quick-Reference Checklist for Your Next Round

- On the tee: Athletic stance, full shoulder turn, swing through the ball, hold your finish.

- On the green: Quiet wrists, shoulder rock, solid start line, and commit to the pace.

- In your head: Clear target, decisive pre-shot routine, bold but smart decisions, and a short memory.

Use this checklist before each golf shot, and you’ll steadily unlock Arnold Palmer’s genius: driving longer, putting truer, and watching your scores move in the right direction.